Undergrad_Book_16-18_Pge_View_Print_no print marks_compressed

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Selected Projects 20<strong>16</strong>-<strong>18</strong><br />

The first and possibly most instinctive way to<br />

analyze photography of the post-industrial ruin is<br />

from the perspective of memory and <strong>no</strong>stalgia. In<br />

describing the famous photographs of abandoned<br />

factories taken by her and her husband, Hilla Becher<br />

says, “the olden days will never come back… there<br />

is <strong>no</strong>thing left of the facilities but memories.” In that<br />

same interview, Becher discussed how her husband<br />

began to photograph factory ruins as a method of<br />

preserving them and the memories they held (Becher<br />

2012). The post-industrial ruin, from the moment<br />

of the industry’s closing in America, was doomed<br />

to crumble. Although the factory workers were <strong>no</strong>t<br />

living incredibly prosperous lives, the buildings still<br />

represented the American Dream. The time of the<br />

American factory was a time of self-made men and<br />

affordable goals. The factory was a way to set out on<br />

the path to prosperity, a fair-paying job that paved<br />

the road to success. The Bechers’ photographs<br />

reflect the sudden loss of a pervasive dream. The<br />

world rapidly changed, leaving many without steady<br />

jobs and a predictable role in society. With the eco<strong>no</strong>mic<br />

downturn and outsourcing came turmoil. The<br />

Bechers’ abandoned coal tipple reminds the viewer<br />

of the coal workers who had built lives around the<br />

industry, lives that were made suddenly transient.<br />

The reminiscence surrounding ruins is <strong>no</strong>t entirely<br />

in<strong>no</strong>cent. Looking <strong>no</strong>stalgically back can inspire<br />

“ideological phantasms” (Huyssen, 2011) where we<br />

imagine better, more simple pasts and void this period<br />

of American history of its underpinnings of racism,<br />

sexism, and classism. Many argue for a return<br />

to the factory period and neglect to ack<strong>no</strong>wledge<br />

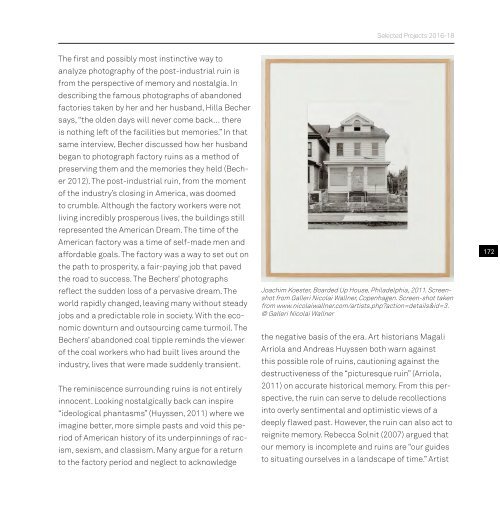

Joachim Koester, Boarded Up House, Philadelphia, 2011. Screenshot<br />

from Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen. Screen-shot taken<br />

from www.nicolaiwallner.com/artists.php?action=details&id=3.<br />

© Galleri Nicolai Wallner<br />

the negative basis of the era. Art historians Magali<br />

Arriola and Andreas Huyssen both warn against<br />

this possible role of ruins, cautioning against the<br />

destructiveness of the “picturesque ruin” (Arriola,<br />

2011) on accurate historical memory. From this perspective,<br />

the ruin can serve to delude recollections<br />

into overly sentimental and optimistic views of a<br />

deeply flawed past. However, the ruin can also act to<br />

reignite memory. Rebecca Solnit (2007) argued that<br />

our memory is incomplete and ruins are “our guides<br />

to situating ourselves in a landscape of time.” Artist<br />

172