Preservings $20 Issue No. 26, 2006 - Home at Plett Foundation

Preservings $20 Issue No. 26, 2006 - Home at Plett Foundation

Preservings $20 Issue No. 26, 2006 - Home at Plett Foundation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

practice actually prevailed,<br />

such as the Frisian reliance on<br />

strong hierarchical leadership,<br />

as opposed to the Flemish congreg<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

model.<br />

A more helpful clue to<br />

discover whether one’s congreg<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

tradition came<br />

from the Flemish or Frisian<br />

churches is through the study of<br />

the backgrounds of congreg<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

themselves. Mennonites<br />

in Prussia tended to settle<br />

according to alliances. The<br />

Gre<strong>at</strong> Marienburger Werder<br />

was largely Flemish in settlement,<br />

with the congreg<strong>at</strong>ions of<br />

Heubuden, Rosenort, Fürstenwerder,<br />

Tiegenhagen and Ladekopp<br />

all characterized as<br />

Flemish. Only Orlofferfelde in<br />

the central Werder was Frisian<br />

in allegiance. In other areas,<br />

such as in the small Marienburger<br />

Werder, across the <strong>No</strong>g<strong>at</strong><br />

river, the Frisian side was<br />

stronger, with congreg<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>at</strong><br />

Thiensdorf and Markushof.<br />

Of the early emigrants to<br />

Russia, most came from the<br />

Gre<strong>at</strong> Werder, hence the strong<br />

Flemish affili<strong>at</strong>ion. Nevertheless,<br />

emigrants who had come<br />

from Frisian churches were<br />

also present in both the colonies of Chortitza<br />

and Molotschna. Only the daughter colony<br />

Bergthal was purposefully settled by just Flemish<br />

Church members, largely in order to avoid<br />

the religious controversies th<strong>at</strong> had occurred<br />

in settling Chortitza almost two gener<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

earlier.<br />

Questions of Ethnic Origins: Flemish or<br />

Frisian?<br />

This question is probably more difficult to<br />

answer than the first. There can be no doubt<br />

th<strong>at</strong> the division itself was largely fueled by the<br />

differences between the two cultures. And even<br />

where the schism was exported to other regions,<br />

cultural differences remained for some time,<br />

which would possibly imply th<strong>at</strong> the separ<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

actually was an ethnic one. For example, in the<br />

Gre<strong>at</strong> Marienburger Werder, evidence seems<br />

to point to the fact th<strong>at</strong> the Frisians and Flemish<br />

actually were following different linguistic<br />

traditions until the l<strong>at</strong>e eighteenth century. The<br />

Flemish congreg<strong>at</strong>ions only began to abandon<br />

Dutch in their church services in the 1760s and<br />

1770s. In contrast, already in 1678 elders and<br />

ministers of the neighbouring Orlofferfelde<br />

(Frisian) congreg<strong>at</strong>ion sent a letter of request<br />

for aid to the Mennonites in Amsterdam, which<br />

was written in High German, 16 suggesting th<strong>at</strong><br />

they did not have the linguistic capacity to write<br />

in the Dutch language.<br />

Nevertheless, it appears as though the ethnic<br />

origins of the two groups were much more fluid<br />

than one would suspect from the names. Already<br />

when the division began, elder Dirk Philips<br />

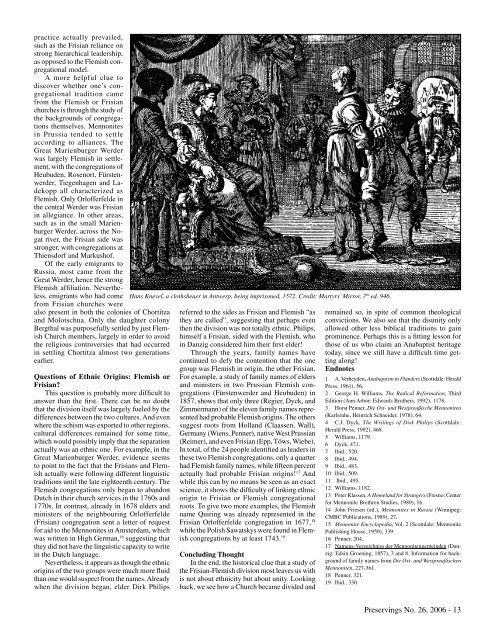

Hans Knevel, a clothsheaer in Antwerp, being imprisoned, 1572. Credit: Martyrs’ Mirror, 7 th ed. 946.<br />

referred to the sides as Frisian and Flemish “as<br />

they are called”, suggesting th<strong>at</strong> perhaps even<br />

then the division was not totally ethnic. Philips,<br />

himself a Frisian, sided with the Flemish, who<br />

in Danzig considered him their first elder!<br />

Through the years, family names have<br />

continued to defy the contention th<strong>at</strong> the one<br />

group was Flemish in origin, the other Frisian.<br />

For example, a study of family names of elders<br />

and ministers in two Prussian Flemish congreg<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

(Fürstenwerder and Heubuden) in<br />

1857, shows th<strong>at</strong> only three (Regier, Dyck, and<br />

Zimmermann) of the eleven family names represented<br />

had probable Flemish origins. The others<br />

suggest roots from Holland (Claassen, Wall),<br />

Germany (Wiens, Penner), n<strong>at</strong>ive West Prussian<br />

(Reimer), and even Frisian (Epp, Töws, Wiebe).<br />

In total, of the 24 people identified as leaders in<br />

these two Flemish congreg<strong>at</strong>ions, only a quarter<br />

had Flemish family names, while fifteen percent<br />

actually had probable Frisian origins! 17 And<br />

while this can by no means be seen as an exact<br />

science, it shows the difficulty of linking ethnic<br />

origin to Frisian or Flemish congreg<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

roots. To give two more examples, the Flemish<br />

name Quiring was already represented in the<br />

Frisian Orlofferfelde congreg<strong>at</strong>ion in 1677, 18<br />

while the Polish Saw<strong>at</strong>skys were found in Flemish<br />

congreg<strong>at</strong>ions by <strong>at</strong> least 1743. 19<br />

Concluding Thought<br />

In the end, the historical clue th<strong>at</strong> a study of<br />

the Frisian-Flemish division most leaves us with<br />

is not about ethnicity but about unity. Looking<br />

back, we see how a Church became divided and<br />

remained so, in spite of common theological<br />

convictions. We also see th<strong>at</strong> the disunity only<br />

allowed other less biblical traditions to gain<br />

prominence. Perhaps this is a fitting lesson for<br />

those of us who claim an Anabaptist heritage<br />

today, since we still have a difficult time getting<br />

along!<br />

Endnotes<br />

1 A. Verheyden, Anabaptism in Flanders (Scottdale: Herald<br />

Press, 1961), 56.<br />

2 George H. Williams, The Radical Reform<strong>at</strong>ion, Third<br />

Edition (Ann Arbor: Edwards Brothers, 1992), 1178.<br />

3 Horst Penner, Die Ost- und Westpreußische Mennoniten<br />

(Karlsruhe, Heinrich Schneider, 1978), 64.<br />

4 C.J. Dyck, The Writings of Dirk Philips (Scottdale:<br />

Herald Press, 1992), 468.<br />

5 Williams, 1179.<br />

6 Dyck, 471.<br />

7 Ibid., 520.<br />

8 Ibid., 494.<br />

9 Ibid., 483.<br />

10 Ibid., 509.<br />

11 Ibid., 495.<br />

12 Williams, 1182.<br />

13 Peter Klassen, A <strong>Home</strong>land for Strangers (Fresno: Center<br />

for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 1989), 16.<br />

14 John Friesen (ed.), Mennonites in Russia (Winnipeg:<br />

CMBC Public<strong>at</strong>ions, 1989), 27.<br />

15 Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2 (Scottdale: Mennonite<br />

Publishing House, 1959), 339.<br />

16 Penner, 204.<br />

17 Namens-Verzeichniss der Mennonitengemeinden (Danzig:<br />

Edsin Groening, 1857), 3 and 8. Inform<strong>at</strong>ion for background<br />

of family names from Die Ost- und Westpreußischen<br />

Mennoniten, 227-361.<br />

18 Penner, 321.<br />

19 Ibid., 330.<br />

<strong>Preservings</strong> <strong>No</strong>. <strong>26</strong>, <strong>2006</strong> - 13