Conference Programme (PDF, 1019KB) - Trinity College Dublin

Conference Programme (PDF, 1019KB) - Trinity College Dublin

Conference Programme (PDF, 1019KB) - Trinity College Dublin

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

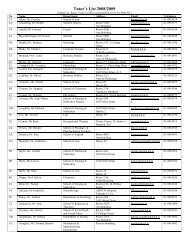

abstracts by stream and session<br />

East Europeans are not identified in immigration policy for explicitly racial reasons; rather they have been selected for other reasons – in<br />

this case to fill a perceived gap in the low-end sectors of the economy. These policies did not invoke racial categories in a sense because<br />

they didn’t have to: by choosing migrants from the EU, the UK implicitly chose white migrants. In the second part of the paper, we turn to<br />

the ways in which these migrations and migrants have been presented and discussed British national print media over the past six years.<br />

We adopt a frame-analytic approach here to argue that the media’s framing of these migrations has contributed to their overall<br />

racialisation. Concerns over the economic impact of migration, the strain migrants place on services, and cultural integration invoke and<br />

evoke racialised understandings of migration. We find this process more pronounced with respect to Romanians than Hungarians. In<br />

sum, we present evidence to demonstrate that both the state and the media contribute to racialised understanding of East European<br />

migration.<br />

Difficult come backs. Some re-adaptation problems of Polish migrants.<br />

Monika Banas, Jagiellonian University, Poland<br />

Since Poland joined the structures of the united Europe and most of the EU countries opened their labour markets to Polish citizens,<br />

nearly two million people left Poland and settled in other EU countries. Waves of migration headed mostly towards the British Islands,<br />

Ireland, Sweden and other Nordic countries as well as towards France, Spain and Germany.<br />

A number of complimentary pull and push factors were behind the size of the 2004-2009 wave of migration. They were of predominantly<br />

economic nature and were associated with both the country of origin as well as with the countries of destination. In the recipient<br />

countries, deficits of available workforce in some sectors of economy played a crucial role in accommodating the influx of migrants. On<br />

the other hand, among factors of a different kind, there were also the psychological ones, associated e.g. with migrants’ readiness to<br />

explore new places and discover new cultures.<br />

For Polish migrants, mostly young people, years of work and study abroad allowed them to experience different organization of life and a<br />

different life quality. This experience influenced the modification of their self-identity and changed earlier hierarchies of the recognized<br />

values. Some of these changes became evident already during the emigration period, other however, emerged only upon the return to the<br />

home country.<br />

For many of those who decide to come back to Poland, life after return brings problems of rather unexpected nature. They result mainly<br />

from to the still persisting economic, political and societal differences between Poland and the older countries of the EU. Confronting the<br />

old reality, which migrants originally left behind when leaving Poland, may often lead them towards situations of psychological crisis.<br />

These crises arise around e.g. the difficulties with re-entering to the societal structures of the home country. New research based on<br />

surveys and interviews with individuals who returned after some years abroad, show a worrying picture. It is a picture of a fraction of<br />

society, who after an initial period of an attempt to accommodate back to Polish realities fails to do so. It subsequently rejects the rules of<br />

social life which dominate in Poland. Societal values incorporated during the migrants’ life abroad, to a greater or lesser extent modify the<br />

migrants’ worldview as well as the way these mostly young people think and act in their later life. A remedy for this unexpected problem<br />

comes usually in the form of a decision to emigrate again. However, this time, the plans are usually to emigrate for much longer than<br />

previously. In many cases, the plans envisage repatriating to Poland only for the retirement.<br />

In cooperation with non governmental organizations, Polish state institutions organize targeted schemes to facilitate bringing migrants<br />

back home. Although many individuals participate in the schemes, this alone does not reflect the success of these measures. For the<br />

returning migrants to re-enter the domestic labour market, of paramount importance are such matters as remuneration, employment or<br />

self-employment. These issues require more effective approaches to be applied. Next to an economic one, the other key problem that<br />

occurs in this domain is of rather psychological and social nature. It is associated with migrants’ return to the local domestic social<br />

structures. Not seldom, returning migrants feel not accepted and not understood by those around them who have no migration<br />

experience. Threat of social ostracism becomes yet another reason, a very strong one indeed, to emigrate again.<br />

This article portrays the situation of young Poles who decided to return to Poland after some years abroad. It presents the detailed nature,<br />

character and origin of the phenomenon of re-adaptation problems of Polish migrants, leading many of them to emigrate again.<br />

Determinants of Return Migration: Evidence from Migrants living in South Africa<br />

Daniel Makina, University of South Africa, South Africa<br />

It is rare for migration to become a one-way traffic. It has been observed that a migrant has conscious intention to return to the home<br />

country. While return migration has not been widely researched, there is considerable evidence that indicates that a large proportion of<br />

migrants actually do return to their countries of origin. For example, it is estimated that 30% of the migrants that went to the USA<br />

between 1908 and 1957 returned home (Gosh, 2000). Elsewhere, an estimated 85% of Greeks migrating to West Germany between 1960<br />

and 1984 gradually returned home (Glytsos, 1988). In the literature four main reasons are cited (Cerase, 1974). First, there are those who<br />

return after failing to get jobs that are necessary for survival and be able to send remittances back home. Second, there are those who<br />

return after realizing that they cannot live in a different culture away from family and friends. Third, there are those who return to retire<br />

after earning enough money. Fourth, there are those who return to practice their new skills in the home country after human capital<br />

accumulation in the immigration country.<br />

In Africa, the major destination of migrants is South Africa, the economic powerhouse of the continent. While South Africa has had an<br />

enduring migration relationship with neighbouring countries that dates back to the discovery of diamonds and gold mines in the 19th<br />

95