The Border of Farming and the Cultural Markers - Nordlige Verdener

The Border of Farming and the Cultural Markers - Nordlige Verdener

The Border of Farming and the Cultural Markers - Nordlige Verdener

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

84<br />

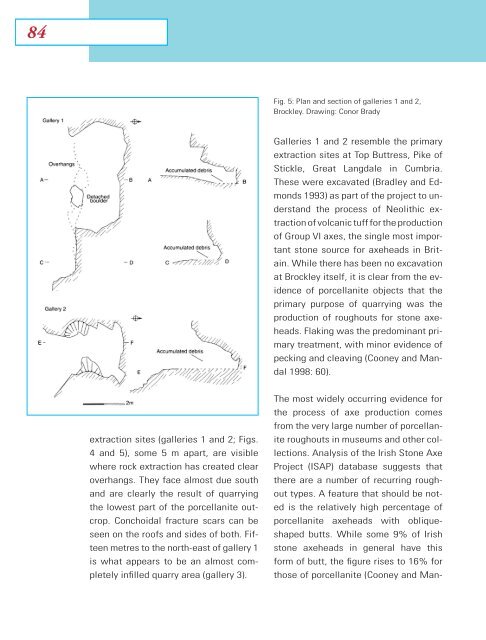

Fig. 5: Plan <strong>and</strong> section <strong>of</strong> galleries 1 <strong>and</strong> 2,<br />

Brockley. Drawing: Conor Brady<br />

Galleries 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 resemble <strong>the</strong> primary<br />

extraction sites at Top Buttress, Pike <strong>of</strong><br />

Stickle, Great Langdale in Cumbria.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se were excavated (Bradley <strong>and</strong> Edmonds<br />

1993) as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project to underst<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> Neolithic extraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> volcanic tuff for <strong>the</strong> production<br />

<strong>of</strong> Group VI axes, <strong>the</strong> single most important<br />

stone source for axeheads in Britain.<br />

While <strong>the</strong>re has been no excavation<br />

at Brockley itself, it is clear from <strong>the</strong> evidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> porcellanite objects that <strong>the</strong><br />

primary purpose <strong>of</strong> quarrying was <strong>the</strong><br />

production <strong>of</strong> roughouts for stone axeheads.<br />

Flaking was <strong>the</strong> predominant primary<br />

treatment, with minor evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

pecking <strong>and</strong> cleaving (Cooney <strong>and</strong> M<strong>and</strong>al<br />

1998: 60).<br />

extraction sites (galleries 1 <strong>and</strong> 2; Figs.<br />

4 <strong>and</strong> 5), some 5 m apart, are visible<br />

where rock extraction has created clear<br />

overhangs. <strong>The</strong>y face almost due south<br />

<strong>and</strong> are clearly <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> quarrying<br />

<strong>the</strong> lowest part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> porcellanite outcrop.<br />

Conchoidal fracture scars can be<br />

seen on <strong>the</strong> ro<strong>of</strong>s <strong>and</strong> sides <strong>of</strong> both. Fifteen<br />

metres to <strong>the</strong> north-east <strong>of</strong> gallery 1<br />

is what appears to be an almost completely<br />

infilled quarry area (gallery 3).<br />

<strong>The</strong> most widely occurring evidence for<br />

<strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> axe production comes<br />

from <strong>the</strong> very large number <strong>of</strong> porcellanite<br />

roughouts in museums <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r collections.<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Irish Stone Axe<br />

Project (ISAP) database suggests that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are a number <strong>of</strong> recurring roughout<br />

types. A feature that should be noted<br />

is <strong>the</strong> relatively high percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

porcellanite axeheads with obliqueshaped<br />

butts. While some 9% <strong>of</strong> Irish<br />

stone axeheads in general have this<br />

form <strong>of</strong> butt, <strong>the</strong> figure rises to 16% for<br />

those <strong>of</strong> porcellanite (Cooney <strong>and</strong> Man-