Architect Drawings : A Selection of Sketches by World Famous Architects Through History

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

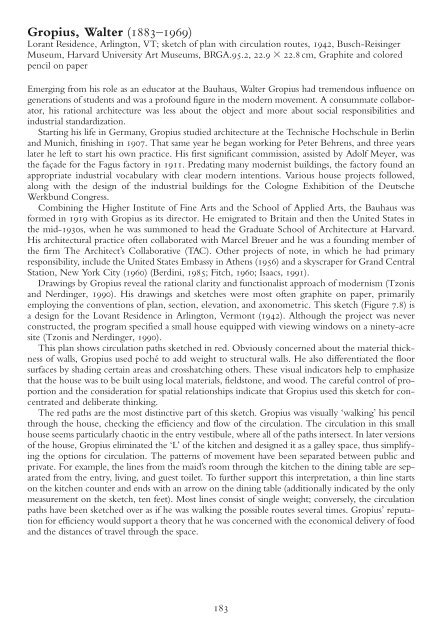

Gropius, Walter (1883–1969)<br />

Lorant Residence, Arlington, VT; sketch <strong>of</strong> plan with circulation routes, 1942, Busch-Reisinger<br />

Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, BRGA.95.2, 22.9 22.8 cm, Graphite and colored<br />

pencil on paper<br />

Emerging from his role as an educator at the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius had tremendous influence on<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> students and was a pr<strong>of</strong>ound figure in the modern movement. A consummate collaborator,<br />

his rational architecture was less about the object and more about social responsibilities and<br />

industrial standardization.<br />

Starting his life in Germany, Gropius studied architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin<br />

and Munich, finishing in 1907. That same year he began working for Peter Behrens, and three years<br />

later he left to start his own practice. His first significant commission, assisted <strong>by</strong> Adolf Meyer, was<br />

the façade for the Fagus factory in 1911. Predating many modernist buildings, the factory found an<br />

appropriate industrial vocabulary with clear modern intentions. Various house projects followed,<br />

along with the design <strong>of</strong> the industrial buildings for the Cologne Exhibition <strong>of</strong> the Deutsche<br />

Werkbund Congress.<br />

Combining the Higher Institute <strong>of</strong> Fine Arts and the School <strong>of</strong> Applied Arts, the Bauhaus was<br />

formed in 1919 with Gropius as its director. He emigrated to Britain and then the United States in<br />

the mid-1930s, when he was summoned to head the Graduate School <strong>of</strong> <strong>Architect</strong>ure at Harvard.<br />

His architectural practice <strong>of</strong>ten collaborated with Marcel Breuer and he was a founding member <strong>of</strong><br />

the firm The <strong>Architect</strong>’s Collaborative (TAC). Other projects <strong>of</strong> note, in which he had primary<br />

responsibility, include the United States Embassy in Athens (1956) and a skyscraper for Grand Central<br />

Station, New York City (1960) (Berdini, 1985; Fitch, 1960; Isaacs, 1991).<br />

<strong>Drawings</strong> <strong>by</strong> Gropius reveal the rational clarity and functionalist approach <strong>of</strong> modernism (Tzonis<br />

and Nerdinger, 1990). His drawings and sketches were most <strong>of</strong>ten graphite on paper, primarily<br />

employing the conventions <strong>of</strong> plan, section, elevation, and axonometric. This sketch (Figure 7.8) is<br />

a design for the Lovant Residence in Arlington, Vermont (1942). Although the project was never<br />

constructed, the program specified a small house equipped with viewing windows on a ninety-acre<br />

site (Tzonis and Nerdinger, 1990).<br />

This plan shows circulation paths sketched in red. Obviously concerned about the material thickness<br />

<strong>of</strong> walls, Gropius used poché to add weight to structural walls. He also differentiated the floor<br />

surfaces <strong>by</strong> shading certain areas and crosshatching others. These visual indicators help to emphasize<br />

that the house was to be built using local materials, fieldstone, and wood. The careful control <strong>of</strong> proportion<br />

and the consideration for spatial relationships indicate that Gropius used this sketch for concentrated<br />

and deliberate thinking.<br />

The red paths are the most distinctive part <strong>of</strong> this sketch. Gropius was visually ‘walking’ his pencil<br />

through the house, checking the efficiency and flow <strong>of</strong> the circulation. The circulation in this small<br />

house seems particularly chaotic in the entry vestibule, where all <strong>of</strong> the paths intersect. In later versions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the house, Gropius eliminated the ‘L’ <strong>of</strong> the kitchen and designed it as a galley space, thus simplifying<br />

the options for circulation. The patterns <strong>of</strong> movement have been separated between public and<br />

private. For example, the lines from the maid’s room through the kitchen to the dining table are separated<br />

from the entry, living, and guest toilet. To further support this interpretation, a thin line starts<br />

on the kitchen counter and ends with an arrow on the dining table (additionally indicated <strong>by</strong> the only<br />

measurement on the sketch, ten feet). Most lines consist <strong>of</strong> single weight; conversely, the circulation<br />

paths have been sketched over as if he was walking the possible routes several times. Gropius’ reputation<br />

for efficiency would support a theory that he was concerned with the economical delivery <strong>of</strong> food<br />

and the distances <strong>of</strong> travel through the space.<br />

183