Journal for the Study of Antisemitism

Journal for the Study of Antisemitism

Journal for the Study of Antisemitism

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

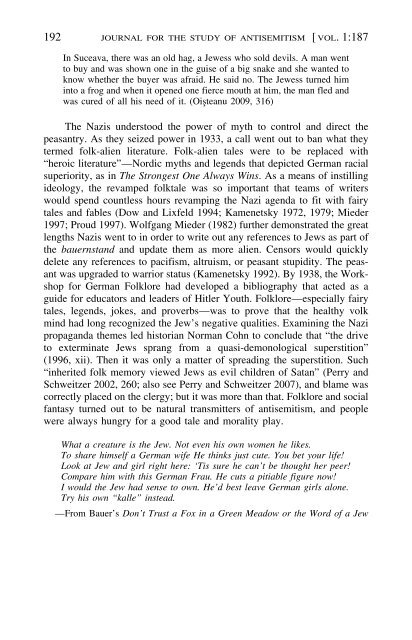

192 JOURNAL FOR THE STUDY OF ANTISEMITISM [ VOL. 1:187<br />

In Suceava, <strong>the</strong>re was an old hag, a Jewess who sold devils. A man went<br />

to buy and was shown one in <strong>the</strong> guise <strong>of</strong> a big snake and she wanted to<br />

know whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> buyer was afraid. He said no. The Jewess turned him<br />

into a frog and when it opened one fierce mouth at him, <strong>the</strong> man fled and<br />

was cured <strong>of</strong> all his need <strong>of</strong> it. (Oi¸steanu 2009, 316)<br />

The Nazis understood <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> myth to control and direct <strong>the</strong><br />

peasantry. As <strong>the</strong>y seized power in 1933, a call went out to ban what <strong>the</strong>y<br />

termed folk-alien literature. Folk-alien tales were to be replaced with<br />

“heroic literature”—Nordic myths and legends that depicted German racial<br />

superiority, as in The Strongest One Always Wins. As a means <strong>of</strong> instilling<br />

ideology, <strong>the</strong> revamped folktale was so important that teams <strong>of</strong> writers<br />

would spend countless hours revamping <strong>the</strong> Nazi agenda to fit with fairy<br />

tales and fables (Dow and Lixfeld 1994; Kamenetsky 1972, 1979; Mieder<br />

1997; Proud 1997). Wolfgang Mieder (1982) fur<strong>the</strong>r demonstrated <strong>the</strong> great<br />

lengths Nazis went to in order to write out any references to Jews as part <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> bauernstand and update <strong>the</strong>m as more alien. Censors would quickly<br />

delete any references to pacifism, altruism, or peasant stupidity. The peasant<br />

was upgraded to warrior status (Kamenetsky 1992). By 1938, <strong>the</strong> Workshop<br />

<strong>for</strong> German Folklore had developed a bibliography that acted as a<br />

guide <strong>for</strong> educators and leaders <strong>of</strong> Hitler Youth. Folklore—especially fairy<br />

tales, legends, jokes, and proverbs—was to prove that <strong>the</strong> healthy volk<br />

mind had long recognized <strong>the</strong> Jew’s negative qualities. Examining <strong>the</strong> Nazi<br />

propaganda <strong>the</strong>mes led historian Norman Cohn to conclude that “<strong>the</strong> drive<br />

to exterminate Jews sprang from a quasi-demonological superstition”<br />

(1996, xii). Then it was only a matter <strong>of</strong> spreading <strong>the</strong> superstition. Such<br />

“inherited folk memory viewed Jews as evil children <strong>of</strong> Satan” (Perry and<br />

Schweitzer 2002, 260; also see Perry and Schweitzer 2007), and blame was<br />

correctly placed on <strong>the</strong> clergy; but it was more than that. Folklore and social<br />

fantasy turned out to be natural transmitters <strong>of</strong> antisemitism, and people<br />

were always hungry <strong>for</strong> a good tale and morality play.<br />

What a creature is <strong>the</strong> Jew. Not even his own women he likes.<br />

To share himself a German wife He thinks just cute. You bet your life!<br />

Look at Jew and girl right here: ‘Tis sure he can’t be thought her peer!<br />

Compare him with this German Frau. He cuts a pitiable figure now!<br />

I would <strong>the</strong> Jew had sense to own. He’d best leave German girls alone.<br />

Try his own “kalle” instead.<br />

—From Bauer’s Don’t Trust a Fox in a Green Meadow or <strong>the</strong> Word <strong>of</strong> a Jew