to download report - Geological Survey of Ireland

to download report - Geological Survey of Ireland

to download report - Geological Survey of Ireland

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

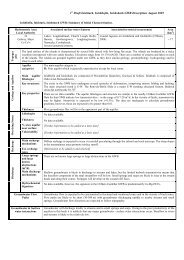

Two simplified hypothetical examples serve <strong>to</strong> mark the extremes <strong>of</strong> high and low risk. An overhanging cliff facethat is considered <strong>to</strong> be active, in the sense that rock falls are a frequent occurrence, situated in a remote andinaccessible mountain valley, will have a negligible risk associated with it. However <strong>to</strong> build a school under acliff face even if the cliff has been stable for as long as records have been maintained would pose an unacceptablyhigh risk because <strong>of</strong> the adverse impacts on human life and property that would follow a failure in the cliff face.The upper right cell in Fig. 5.1 represents the first case while the latter case <strong>of</strong> the school would be situated<strong>to</strong>wards the lower left corner.Fig. 5.1 Example <strong>of</strong> qualitative risk matrix (after Lee and Jones, 2004)The extent <strong>of</strong> risk occurring between these two extremes is harder <strong>to</strong> determine and yet is arguably much moreimportant <strong>to</strong> fully understand. Low <strong>to</strong> medium magnitude events will <strong>of</strong>ten attract less attention than highmagnitude events, and the probability <strong>of</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong> all magnitude events is <strong>of</strong>ten not well unders<strong>to</strong>od. Putanother way, just because we have no record <strong>of</strong> damaging landslides in an area does not mean that theycannot occur. The situation can therefore arise that human development and activity will occur in areas <strong>of</strong> highlandslide risk, primarily because the hazard has not been identified and consequently the risk not assessed.Types <strong>of</strong> Risk assessmentThere are two main approaches <strong>to</strong> presenting an assessment <strong>of</strong> risk. These are:Qualitative risk assessment. This involves the expression <strong>of</strong> the likelihood <strong>of</strong> an event occurring and theextent <strong>of</strong> its adverse consequences being expressed qualitatively. The most common representation <strong>of</strong> qualitativerisk assessment is in the form <strong>of</strong> risk matrices as shown in Fig. 5.1.Quantitative risk assessment. This involves quantifying the probability <strong>of</strong> an event occurring and expressingin real terms the losses that would arise from such an event.It might be possible <strong>to</strong> include a third broad category here which would span these two approaches. This form<strong>of</strong> risk assessment might include an expression <strong>of</strong> the probability <strong>of</strong> an event occurring with a qualitativerepresentation <strong>of</strong> the adverse costs, or a qualitative expression <strong>of</strong> the likelihood <strong>of</strong> an event with a quantification<strong>of</strong> resulting costs.While at first glance, quantitative risk assessment would appear <strong>to</strong> be the most desirable, in practice theattainment <strong>of</strong> an accurate estimation <strong>of</strong> risk in this form is extremely challenging, if not impossible in an Irishcontext. The requirement <strong>of</strong> extensive amounts <strong>of</strong> data <strong>to</strong> estimate the probability fac<strong>to</strong>r alone most likelyexcludes its use in this country. Fundamentally as a method it is extremely vulnerable <strong>to</strong> the criticism <strong>of</strong> falseprecision, where the expression <strong>of</strong> risk in numerical terms makes it appear more accurate than it actually is.On the other hand the benefit <strong>of</strong> qualitative risk assessment is that it is simply expressed and thereforeperhaps more easily unders<strong>to</strong>od. This <strong>to</strong>o has its weakness in that it could be argued that the method isgrossly over-simplistic as an approach <strong>to</strong> dealing with landslide hazard. It may be the case that in <strong>Ireland</strong> themost appropriate, and importantly, the most pragmatic approach would aim <strong>to</strong>wards a semi-quantitative methodwhere a qualitative expression <strong>of</strong> likelihood is combined with a detailed estimation <strong>of</strong> the potential costs arisingfrom a landslide.Such a method would potentially result in a very powerful <strong>to</strong>ol <strong>to</strong> assist the appropriate authorities in dealingwith landslide hazard in <strong>Ireland</strong>. In areas where a strong case for the potential <strong>of</strong> landslide hazard is identified,local authorities could adjust planning guidance as necessary. Similarly, infrastructure providers could takeaccount <strong>of</strong> the estimated potential loss in real terms when deciding on the location <strong>of</strong> assets such as powerlines. Even agencies charged with matters such as the management <strong>of</strong> natural resources would have valuableinformation <strong>to</strong> aid in their management strategy and <strong>to</strong> guide them in a cost-benefit analysis <strong>of</strong> implementingmitigation measures <strong>to</strong> the potential damage caused by landslides. The peat landslide in Derrybrien in 2003 isestimated <strong>to</strong> have killed over 50,000 fish (SRFB, 2003).34