- Page 5 and 6:

TABLE OF CONTENTSAuthor Team for th

- Page 8 and 9:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 10 and 11:

PREFACEReport Motivation and Guidan

- Page 12 and 13:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 14 and 15:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 16 and 17:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 18 and 19:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 21 and 22:

1CHAPTERAbrupt Climate ChangeIntrod

- Page 23 and 24:

Abrupt Climate Change-35Arctic temp

- Page 25 and 26:

Abrupt Climate ChangeFigure 1.2. Po

- Page 27 and 28:

Abrupt Climate Changewell below sea

- Page 29 and 30:

Abrupt Climate Changeheterogeneous

- Page 31 and 32:

Abrupt Climate Changeapart from dro

- Page 33 and 34:

Abrupt Climate Change6. Abrupt Chan

- Page 35 and 36:

Abrupt Climate Changeintermediate c

- Page 37 and 38:

Abrupt Climate Changeper square met

- Page 39:

Abrupt Climate Changeis the norther

- Page 42 and 43:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 44:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 47 and 48:

Abrupt Climate ChangeRegardless how

- Page 49 and 50:

Abrupt Climate Changecentrations, a

- Page 51 and 52:

Abrupt Climate ChangeBox 2.1. Glaci

- Page 53 and 54:

Abrupt Climate Changetime. Degree-d

- Page 55 and 56:

Abrupt Climate Changetion, and accu

- Page 57 and 58:

Abrupt Climate ChangeBox 2.2. Mass

- Page 59 and 60:

Abrupt Climate Changeof the glacier

- Page 61 and 62:

Abrupt Climate ChangeFigure 2.6. Ra

- Page 63 and 64:

Abrupt Climate Changewater) or, mor

- Page 65 and 66:

Abrupt Climate ChangeFigure 2.7. Re

- Page 67 and 68:

Abrupt Climate Changeresults in a l

- Page 69 and 70:

Abrupt Climate Changeis not providi

- Page 71 and 72:

Abrupt Climate Changemeasurements c

- Page 73 and 74:

Abrupt Climate Changemore than 10,0

- Page 75 and 76:

Abrupt Climate Changeocean models h

- Page 77 and 78:

Abrupt Climate Changeto atmosphere-

- Page 79 and 80:

3CHAPTERHydrological Variability an

- Page 81 and 82:

Abrupt Climate Change• The integr

- Page 83 and 84:

Abrupt Climate Changethe soil (King

- Page 85 and 86:

Abrupt Climate Changeon (Kaplan et

- Page 87 and 88:

Abrupt Climate Changeorbital-time-s

- Page 89 and 90:

Abrupt Climate ChangeFigure 3.4. (t

- Page 91 and 92:

Abrupt Climate Changemodels forced

- Page 93 and 94: Abrupt Climate ChangeBox 3.2. Waves

- Page 95 and 96: Abrupt Climate Changebecause (1) th

- Page 97 and 98: Abrupt Climate ChangeHarrison et al

- Page 99 and 100: Abrupt Climate Changethat even the

- Page 101 and 102: Abrupt Climate Changethat seen afte

- Page 103 and 104: Abrupt Climate Changeentire period

- Page 105 and 106: Abrupt Climate Changelong-lived gre

- Page 107 and 108: Abrupt Climate Changeplanetary-scal

- Page 109 and 110: Abrupt Climate ChangeBox 3.3. Paleo

- Page 111 and 112: Abrupt Climate Changerelated to the

- Page 113 and 114: Abrupt Climate Changeinto the North

- Page 115 and 116: Abrupt Climate ChangeThe summertime

- Page 117 and 118: Abrupt Climate Change(Anderson et a

- Page 119 and 120: Abrupt Climate ChangeHere the model

- Page 121 and 122: Abrupt Climate Changetropical tropo

- Page 123 and 124: Abrupt Climate Changefunctions; Koc

- Page 125 and 126: Abrupt Climate Changechanges than t

- Page 127: Abrupt Climate Changeboundary condi

- Page 130 and 131: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

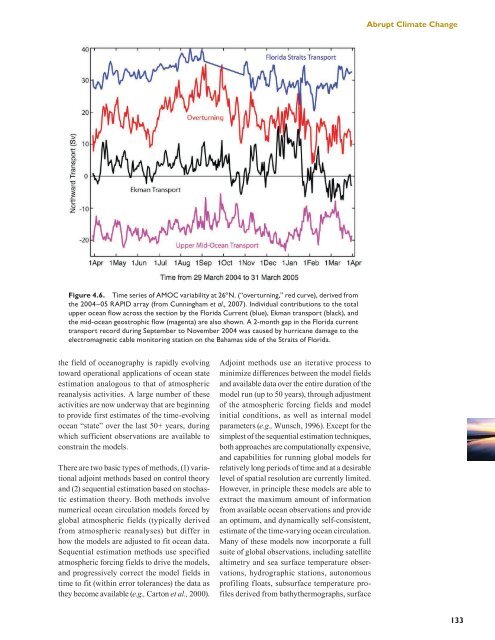

- Page 132 and 133: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 134 and 135: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 136 and 137: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 138 and 139: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 140 and 141: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 142 and 143: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 146 and 147: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 148 and 149: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 150 and 151: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 152 and 153: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 154 and 155: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 156 and 157: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 158 and 159: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 160 and 161: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 162 and 163: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 164 and 165: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 166 and 167: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 168 and 169: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 170 and 171: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 172 and 173: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 174 and 175: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 176 and 177: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 178 and 179: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 180 and 181: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 182 and 183: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 184 and 185: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 186 and 187: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 188 and 189: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 190 and 191: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 192 and 193: The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 194 and 195:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 196 and 197:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 198 and 199:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 200 and 201:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 202 and 203:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 204 and 205:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 206 and 207:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 208 and 209:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 210 and 211:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 212 and 213:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 214 and 215:

202REFERENCESChapter 1 ReferencesAl

- Page 216 and 217:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 218 and 219:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 220 and 221:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 222 and 223:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 224 and 225:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 226 and 227:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 228 and 229:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 230 and 231:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 232 and 233:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 234 and 235:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 236 and 237:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 238 and 239:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 240 and 241:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 242 and 243:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 244 and 245:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 246 and 247:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 248 and 249:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 250 and 251:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 252 and 253:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 254 and 255:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 256 and 257:

The U.S. Climate Change Science Pro

- Page 258:

U.S. Climate Change Science Program