Full report. - Social Research and Demonstration Corp

Full report. - Social Research and Demonstration Corp

Full report. - Social Research and Demonstration Corp

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

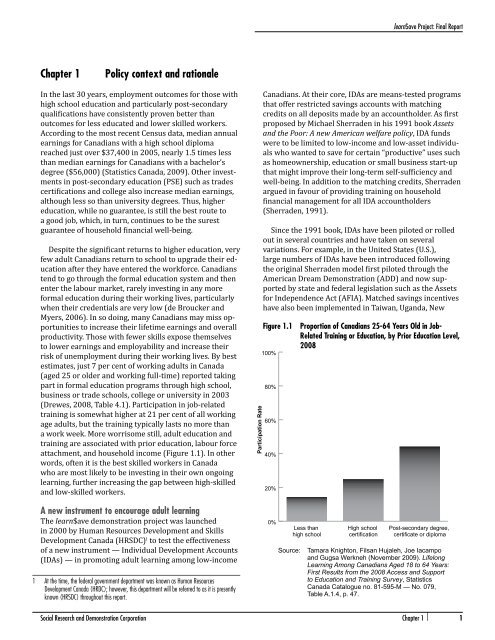

learn$ave Project: Final ReportChapter 1Policy context <strong>and</strong> rationaleIn the last 30 years, employment outcomes for those withhigh school education <strong>and</strong> particularly post-secondaryqualifications have consistently proven better thanoutcomes for less educated <strong>and</strong> lower skilled workers.According to the most recent Census data, median annualearnings for Canadians with a high school diplomareached just over $37,400 in 2005, nearly 1.5 times lessthan median earnings for Canadians with a bachelor’sdegree ($56,000) (Statistics Canada, 2009). Other investmentsin post-secondary education (PSE) such as tradescertifications <strong>and</strong> college also increase median earnings,although less so than university degrees. Thus, highereducation, while no guarantee, is still the best route toa good job, which, in turn, continues to be the surestguarantee of household financial well-being.Despite the significant returns to higher education, veryfew adult Canadians return to school to upgrade their educationafter they have entered the workforce. Canadianstend to go through the formal education system <strong>and</strong> thenenter the labour market, rarely investing in any moreformal education during their working lives, particularlywhen their credentials are very low (de Broucker <strong>and</strong>Myers, 2006). In so doing, many Canadians may miss opportunitiesto increase their lifetime earnings <strong>and</strong> overallproductivity. Those with fewer skills expose themselvesto lower earnings <strong>and</strong> employability <strong>and</strong> increase theirrisk of unemployment during their working lives. By bestestimates, just 7 per cent of working adults in Canada(aged 25 or older <strong>and</strong> working full-time) <strong>report</strong>ed takingpart in formal education programs through high school,business or trade schools, college or university in 2003(Drewes, 2008, Table 4.1). Participation in job-relatedtraining is somewhat higher at 21 per cent of all workingage adults, but the training typically lasts no more thana work week. More worrisome still, adult education <strong>and</strong>training are associated with prior education, labour forceattachment, <strong>and</strong> household income (Figure 1.1). In otherwords, often it is the best skilled workers in Canadawho are most likely to be investing in their own ongoinglearning, further increasing the gap between high-skilled<strong>and</strong> low-skilled workers.A new instrument to encourage adult learningThe learn$ave demonstration project was launchedin 2000 by Human Resources Development <strong>and</strong> SkillsDevelopment Canada (HRSDC) 1 to test the effectivenessof a new instrument — Individual Development Accounts(IDAs) — in promoting adult learning among low-income1 At the time, the federal government department was known as Human ResourcesDevelopment Canada (HRDC); however, this department will be referred to as it is presentlyknown (HRSDC) throughout this <strong>report</strong>.Participation RateCanadians. At their core, IDAs are means-tested programsthat offer restricted savings accounts with matchingcredits on all deposits made by an accountholder. As firstproposed by Michael Sherraden in his 1991 book Assets<strong>and</strong> the Poor: A new American welfare policy, IDA fundswere to be limited to low-income <strong>and</strong> low-asset individualswho wanted to save for certain “productive” uses suchas homeownership, education or small business start-upthat might improve their long-term self-sufficiency <strong>and</strong>well-being. In addition to the matching credits, Sherradenargued in favour of providing training on householdfinancial management for all IDA accountholders(Sherraden, 1991).Since the 1991 book, IDAs have been piloted or rolledout in several countries <strong>and</strong> have taken on severalvariations. For example, in the United States (U.S.),large numbers of IDAs have been introduced followingthe original Sherraden model first piloted through theAmerican Dream <strong>Demonstration</strong> (ADD) <strong>and</strong> now supportedby state <strong>and</strong> federal legislation such as the Assetsfor Independence Act (AFIA). Matched savings incentiveshave also been implemented in Taiwan, Ug<strong>and</strong>a, NewFigure 1.1 Proportion of Canadians 25-64 Years Old in Job-Related Training or Education, by Prior Education Level,2008100%80%60%40%20%0%Source:Less thanhigh schoolHigh schoolcertificationPost-secondary degree,certificate or diplomaTamara Knighton, Filsan Hujaleh, Joe Iacampo<strong>and</strong> Gugsa Werkneh (November 2009). LifelongLearning Among Canadians Aged 18 to 64 Years:First Results from the 2008 Access <strong>and</strong> Supportto Education <strong>and</strong> Training Survey, StatisticsCanada Catalogue no. 81-595-M — No. 079,Table A.1.4, p. 47.<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Demonstration</strong> <strong>Corp</strong>oration Chapter 1 | 1