MacroeconomicsI_working_version (1)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

76<br />

Chapter 8<br />

S<br />

Real wage<br />

Labour Supply<br />

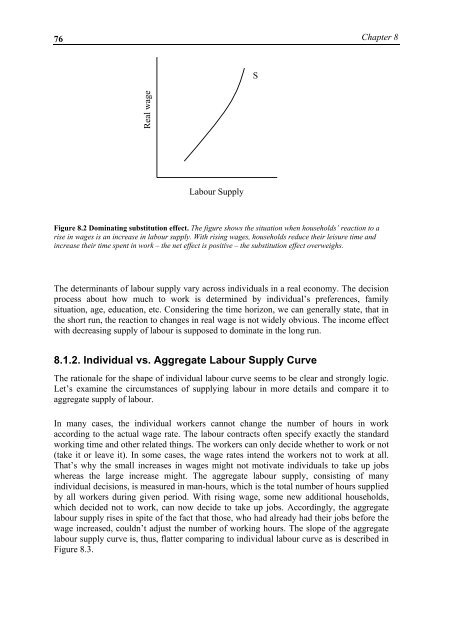

Figure 8.2 Dominating substitution effect. The figure shows the situation when households’ reaction to a<br />

rise in wages is an increase in labour supply. With rising wages, households reduce their leisure time and<br />

increase their time spent in work – the net effect is positive – the substitution effect overweighs.<br />

The determinants of labour supply vary across individuals in a real economy. The decision<br />

process about how much to work is determined by individual’s preferences, family<br />

situation, age, education, etc. Considering the time horizon, we can generally state, that in<br />

the short run, the reaction to changes in real wage is not widely obvious. The income effect<br />

with decreasing supply of labour is supposed to dominate in the long run.<br />

8.1.2. Individual vs. Aggregate Labour Supply Curve<br />

The rationale for the shape of individual labour curve seems to be clear and strongly logic.<br />

Let’s examine the circumstances of supplying labour in more details and compare it to<br />

aggregate supply of labour.<br />

In many cases, the individual workers cannot change the number of hours in work<br />

according to the actual wage rate. The labour contracts often specify exactly the standard<br />

<strong>working</strong> time and other related things. The workers can only decide whether to work or not<br />

(take it or leave it). In some cases, the wage rates intend the workers not to work at all.<br />

That’s why the small increases in wages might not motivate individuals to take up jobs<br />

whereas the large increase might. The aggregate labour supply, consisting of many<br />

individual decisions, is measured in man-hours, which is the total number of hours supplied<br />

by all workers during given period. With rising wage, some new additional households,<br />

which decided not to work, can now decide to take up jobs. Accordingly, the aggregate<br />

labour supply rises in spite of the fact that those, who had already had their jobs before the<br />

wage increased, couldn’t adjust the number of <strong>working</strong> hours. The slope of the aggregate<br />

labour supply curve is, thus, flatter comparing to individual labour curve as is described in<br />

Figure 8.3.