Review of anti-corruption strategies Rob McCusker - Australian ...

Review of anti-corruption strategies Rob McCusker - Australian ...

Review of anti-corruption strategies Rob McCusker - Australian ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

It should be decided whether the focus should be placed upon the <strong>of</strong>fice or the <strong>of</strong>ficeholder. For example,<br />

providing training to <strong>of</strong>ficials to allow them to manage resources in legitimate and effective manner<br />

may simply provide them with transferable skills for a lucrative post outside the corrupt government<br />

department. Equally, a trained <strong>of</strong>ficial in an unresponsive and inherently corrupt department may have little<br />

opportunity to apply that training in a systematic <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> effort.<br />

It is necessary to establish whether the focus <strong>of</strong> the <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> strategy should be placed upon<br />

protecting state revenue through the enhancement <strong>of</strong> the integrity <strong>of</strong>, for example, the tax and customs<br />

agencies or upon investigating evidence <strong>of</strong> criminal activity such as corrupt contract negotiations. The<br />

former will assist in creating financial stability and the latter demonstrate the capacity and commitment <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> efforts.<br />

It must be ascertained whether the aim <strong>of</strong> the <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> strategy is to seek retribution against<br />

malfeasance, or restitution. Aside from the moral case for and against each in the <strong>corruption</strong> context<br />

there remains an issue <strong>of</strong> practicality. The former requires an effective criminal justice system and the<br />

latter would require effective asset tracing and confiscation systems.<br />

An assessment should be undertaken <strong>of</strong> the relative benefits <strong>of</strong> targeting vulnerable departments or<br />

<strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> agencies in terms <strong>of</strong> achieving systematic <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> reform. Risk assessments <strong>of</strong><br />

departments and their procedures may identify important <strong>corruption</strong> vulnerabilities and thereby direct and<br />

enhance <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> efforts.<br />

An assessment should be made <strong>of</strong> donor coordination given that, although virtually all donors have<br />

policies on <strong>corruption</strong>, there is not necessarily an overarching process <strong>of</strong> coordination between donors.<br />

The lack <strong>of</strong> a strategy may result in a number <strong>of</strong> donors operating in a single country with wholly different<br />

aims and objectives, modes <strong>of</strong> operation and conceptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>corruption</strong>.<br />

It has been suggested that the targeting <strong>of</strong> the public sector through processes such as the redrafting<br />

and updating <strong>of</strong> legislation, enhancing the judiciary and ensuring the accountability <strong>of</strong> public service<br />

departments is, while both logical and laudable, time consuming, expensive and prone to relapse.<br />

Similarly, authorising externally appointed and funded agencies to engage with countries on <strong>corruption</strong><br />

issues may have negative impacts, given that such agencies will, without significant host country<br />

government support, possibly be doomed to short-term success and run the risk <strong>of</strong> creating an<br />

atmosphere <strong>of</strong> resentment (and subsequent non-cooperation) among the targeted sectors in that host<br />

country (Doig & Riley 1998).<br />

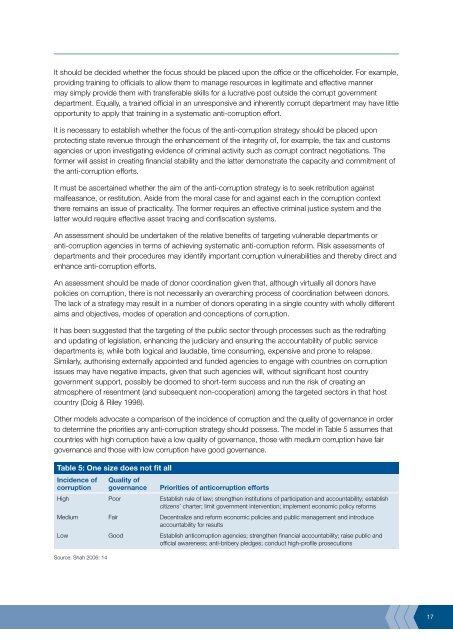

Other models advocate a comparison <strong>of</strong> the incidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>corruption</strong> and the quality <strong>of</strong> governance in order<br />

to determine the priorities any <strong>anti</strong>-<strong>corruption</strong> strategy should possess. The model in Table 5 assumes that<br />

countries with high <strong>corruption</strong> have a low quality <strong>of</strong> governance, those with medium <strong>corruption</strong> have fair<br />

governance and those with low <strong>corruption</strong> have good governance.<br />

Table 5: One size does not fit all<br />

Incidence <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>corruption</strong><br />

Quality <strong>of</strong><br />

governance Priorities <strong>of</strong> <strong>anti</strong><strong>corruption</strong> efforts<br />

High Poor Establish rule <strong>of</strong> law; strengthen institutions <strong>of</strong> participation and accountability; establish<br />

citizens’ charter; limit government intervention; implement economic policy reforms<br />

Medium Fair Decentralize and reform economic policies and public management and introduce<br />

accountability for results<br />

Low Good Establish <strong>anti</strong><strong>corruption</strong> agencies; strengthen financial accountability; raise public and<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficial awareness; <strong>anti</strong>-bribery pledges; conduct high-pr<strong>of</strong>ile prosecutions<br />

Source: Shah 2006: 14