Journal - Comune di Monteleone di Spoleto

Journal - Comune di Monteleone di Spoleto

Journal - Comune di Monteleone di Spoleto

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

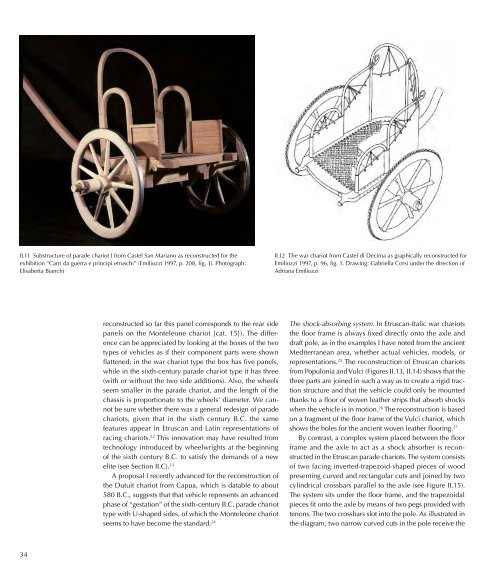

ii.11 Substructure of parade chariot i from Castel San mariano as reconstructed for the<br />

exhibition “Carri da guerra e principi etruschi” (emiliozzi 1997, p. 208, fig. 1). Photo graph:<br />

elisabetta Bianchi<br />

34<br />

reconstructed so far this panel corresponds to the rear side<br />

panels on the monteleone chariot [cat. 15]). The <strong>di</strong>fference<br />

can be appreciated by looking at the boxes of the two<br />

types of vehicles as if their component parts were shown<br />

flattened: in the war chariot type the box has five panels,<br />

while in the sixth-century parade chariot type it has three<br />

(with or without the two side ad<strong>di</strong>tions). also, the wheels<br />

seem smaller in the parade chariot, and the length of the<br />

chassis is proportionate to the wheels’ <strong>di</strong>ameter. We cannot<br />

be sure whether there was a general redesign of parade<br />

chariots, given that in the sixth century B.C. the same<br />

features appear in etruscan and latin representations of<br />

racing chariots. 22 This innovation may have resulted from<br />

technology introduced by wheelwrights at the beginning<br />

of the sixth century B.C. to satisfy the demands of a new<br />

elite (see Section ii.C). 23<br />

a proposal i recently advanced for the reconstruction of<br />

the dutuit chariot from Capua, which is datable to about<br />

580 B.C., suggests that that vehicle represents an advanced<br />

phase of “gestation” of the sixth-century B.C. parade chariot<br />

type with u-shaped sides, of which the monteleone chariot<br />

seems to have become the standard. 24<br />

ii.12 The war chariot from Castel <strong>di</strong> decima as graphically reconstructed for<br />

emiliozzi 1997, p. 96, fig. 1. drawing: Gabriella Corsi under the <strong>di</strong>rection of<br />

adriana emiliozzi<br />

The shock-absorbing system. in etruscan-italic war chariots<br />

the floor frame is always fixed <strong>di</strong>rectly onto the axle and<br />

draft pole, as in the examples i have noted from the ancient<br />

me<strong>di</strong>terranean area, whether actual vehicles, models, or<br />

representations. 25 The reconstruction of etruscan chariots<br />

from Populonia and Vulci (Figures ii.13, ii.14) shows that the<br />

three parts are joined in such a way as to create a rigid traction<br />

structure and that the vehicle could only be mounted<br />

thanks to a floor of woven leather strips that absorb shocks<br />

when the vehicle is in motion. 26 The reconstruction is based<br />

on a fragment of the floor frame of the Vulci chariot, which<br />

shows the holes for the ancient woven leather flooring. 27<br />

By contrast, a complex system placed between the floor<br />

frame and the axle to act as a shock absorber is reconstructed<br />

in the etruscan parade chariots. The system consists<br />

of two facing inverted-trapezoid-shaped pieces of wood<br />

presenting curved and rectangular cuts and joined by two<br />

cylindrical crossbars parallel to the axle (see Figure ii.15).<br />

The system sits under the floor frame, and the trapezoidal<br />

pieces fit onto the axle by means of two pegs provided with<br />

tenons. The two crossbars slot into the pole. as illustrated in<br />

the <strong>di</strong>agram, two narrow curved cuts in the pole receive the