Comparative Parasitology 67(1) 2000 - Peru State College

Comparative Parasitology 67(1) 2000 - Peru State College

Comparative Parasitology 67(1) 2000 - Peru State College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COMPARATIVE PARASITOLOGY, <strong>67</strong>(1), JANUARY <strong>2000</strong><br />

(Leon-Regagnon et al., 1999). Species of Haematoloechus<br />

apparently have experienced a diversification<br />

in frogs and salamanders in central<br />

Mexico, representing the group with the highest<br />

species richness (6) in our samples. Glypthelmins,<br />

parasitic mainly in frogs of the new world,<br />

also shows high species richness. However, the<br />

presence at least of 4 species is mainly the result<br />

of independent host capture events, either from<br />

the neotropical or nearctic zones.<br />

The distribution of the nonendemic frogs from<br />

the lowlands ranges from Ecuador and Colombia<br />

to Veracruz, Mexico (R. vaillanti), to Sonora,<br />

northwestern Mexico (L. melanonotus), and Texas<br />

(S. baudinii). Their digenean fauna in Veracruz<br />

is composed of a combination of neotropical<br />

and nearctic species. Only 2 digenean species,<br />

Glypthelmins sp. and M. monas, were recovered<br />

from L. melanonotus and S. baudinii,<br />

respectively. The former probably represents an<br />

undescribed species, and M. monas has been reported<br />

in numerous host genera in South America<br />

and Africa (Prudhoe and Bray, 1982). Seven<br />

digenean species were collected from R. vaillanti,<br />

and 3 of them show a neotropical distribution:<br />

C. rodriguezi in Panama (Caballero, 1955) and<br />

G. parva in Brazil (Prudhoe and Bray, 1982),<br />

both described from Leptodactylus ocellatus,<br />

and G. facioi in Costa Rica (Brenes et al., 1959)<br />

and Veracruz, Mexico (Razo-Mendivil et al.,<br />

1999), from Rana palmipes Spix, 1824, and R.<br />

vaillanti, respectively. The presence of these<br />

neotropical digeneans in Los Tuxtlas reflects the<br />

geographic distribution of the host genus Leptodactylus<br />

and the "Rana palmipes complex"<br />

(Frost, 1985; Hillis and De Sa, 1988). One species<br />

is endemic, L. (L.) macrocirra, and the 3<br />

remaining species parasitizing R. vaillanti have<br />

a nearctic distribution; 2 of these species (G. attenuata<br />

and C. americanus) are also present in<br />

the endemic frogs of the Transverse Volcanic<br />

Axis, and the third species (H. medioplexus) has<br />

been recorded in several species of frogs from<br />

the United <strong>State</strong>s and Canada, most commonly<br />

in members of the "Rana pipiens complex."<br />

The 3 species have a low host specificity and<br />

have been able to colonize several host groups,<br />

thus expanding their distribution range.<br />

Apparently, a mixture of neotropical and<br />

nearctic species of parasites is taking effect in<br />

the lowlands of the Gulf of Mexico, with a series<br />

of very interesting phenomena of colonization of<br />

new hosts and habitats. Little is known about the<br />

amphibian parasite fauna of the tropical lowlands<br />

of the Pacific slope of Mexico or the<br />

southeastern part of the country. Those areas<br />

will undoubtedly be a source of extensive phylogenetic<br />

and biogeographic information on parasites<br />

and hosts in the future.<br />

Contemporary ecological conditions are also<br />

important determinants of the parasitic fauna of<br />

a host species. Several authors have demonstrated<br />

a marked correlation between the relative<br />

amount of time spent in association with aquatic<br />

habitats and the number of species of platyhelminths<br />

hosted by frogs (Brandt, 1936; Prokopic<br />

and Krivanec, 1975; Brooks, 1976, 1984; Guillen,<br />

1992). Our data clearly demonstrate that<br />

frogs and salamanders harbor the richer digenean<br />

fauna compared with the less water-dependent<br />

hylids or toads, where digeneans were almost<br />

or absolutely absent (the small sample size<br />

in leptodactylids precludes any discussion about<br />

their helminth fauna). Within frogs and salamanders,<br />

diet is the factor that most determines the<br />

richness of the digenean communities. Frogs become<br />

infected when they prey upon insects or<br />

copepods (which is the case in species of Haematoloechus<br />

and Halipegus, respectively), when<br />

they swallow their own skin bearing encysted<br />

metacercariae during ecdysis, or when they feed<br />

upon infected tadpoles (species of Catadiscus,<br />

Cephalogonimus, Glypthelmins, Gorgoderina,<br />

and Megalodiscus) (Yamaguti, 1975; Prudhoe<br />

and Bray, 1982). Salamanders of the genus Ambystoma<br />

Tschudi, 1838, hosted fewer digenean<br />

species than frogs. Garcia-Altamirano et al.<br />

(1993) reported that A. dumerilii in Lake Patzcuaro<br />

feeds mainly on crayfish and fish. As evidenced<br />

by the presence of C. americanus, G.<br />

attenuata, and Haematoloechus spp. in salamanders<br />

of our samples, it is possible that they oc-<br />

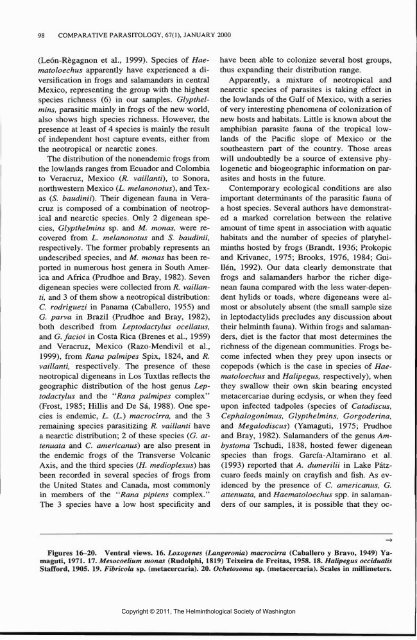

Figures 16-20. Ventral views. 16. Loxogenes (I^angeronia) macrocirra (Caballero y Bravo, 1949) Yamaguti,<br />

1971. 17. Mesocoelium monas (Rudolphi, 1819) Teixeira de Freitas, 1958. 18. Halipegus occidualis<br />

Stafford, 1905. 19. Fibricola sp. (inetacercaria). 20. Ochetosoma sp. (metacercaria). Scales in millimeters.<br />

Copyright © 2011, The Helminthological Society of Washington