- Page 2:

Classical and Romantic Performing P

- Page 6:

Classical and Romantic Performing P

- Page 10:

To Dorothea, who will not read this

- Page 14:

Preface This is the book we have be

- Page 18:

Acknowledgements This book is the r

- Page 22:

Contents INTRODUCTION 1 1ACCENTUATI

- Page 26:

16 PARALIPOMENA 588 The Fermata 588

- Page 30:

Introduction A comprehensive study

- Page 34:

INTRODUCTION 3 supremacy with vario

- Page 38:

INTRODUCTION 5 crescendo or diminue

- Page 42:

1 Accentuation in Theory Accentuati

- Page 46:

and wished to replace it with a cre

- Page 50:

Similar hierarchical principles wer

- Page 54:

Ex. 1.4. Löhlein, Anweisung zum Vi

- Page 58:

CATEGORIES OF ACCENTUATION 15 thems

- Page 62:

CATEGORIES OF ACCENTUATION 17 in th

- Page 66:

aspects of accentuation, however, t

- Page 70:

eats, for the accentual relationshi

- Page 74:

Ex. 1.12. Mozart, Violin Sonata K.

- Page 78:

Ex. 1.15. Türk, Klavierschule, I,

- Page 82:

Ex. 1.16. Sulzer, Allgemeine Theori

- Page 86:

2 Accentuation in Practice In his d

- Page 90:

INDICATIONS OF ACCENT 31 already be

- Page 94:

Ex. 2.2.Türk, Klavierschule, VI,

- Page 98:

and in playing them a considerable

- Page 102:

makes evident the tonality must rec

- Page 106:

Syncopation was, however, often des

- Page 110:

Ex. 2.17.Baillot, L'Art du violon,

- Page 114:

Ex. 2.19.Callcott, Musical Grammar,

- Page 118:

Ex. 2.22.Weber, Mass in E flat J. 2

- Page 122:

INDICATIONS OF ACCENT 47 Ex. 2.24.(

- Page 126:

Ex. 2.27.Garcia, New Treatise, 52 E

- Page 130:

INDICATIONS OF ACCENT 51 all strong

- Page 134:

the first note must not only be mad

- Page 138:

Some revealing examples of this typ

- Page 142:

ass voice by the most distant of hi

- Page 146:

3 The Notation of Accents and Dynam

- Page 150:

Reichardt's assumption that perform

- Page 154:

large number of works where the abs

- Page 158:

Ex. 3.5. Schumann, Violin Sonata op

- Page 162:

NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 67

- Page 166:

Ex. 3.11. Bennett, The Naiads Forte

- Page 170:

Ex. 3.13. Haydn, String Quartet op.

- Page 174:

interesting use of fp by Mozart occ

- Page 178:

NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 75

- Page 182:

Ex. 3.21. Schumann, Fourth Symphony

- Page 186:

NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 79

- Page 190:

Ex. 3.25. Haydn, String Quartet op.

- Page 194:

Ex. 3.28. Beethoven, String Quartet

- Page 198:

Ex. 3.31. Cherubini, Requiem in C m

- Page 202:

Ex. 3.33. Spohr, String Quartet op.

- Page 206:

marking may have been seen as havin

- Page 210:

Ex. 3.38. Haydn, String Quartet op.

- Page 214: NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 93

- Page 218: Ex. 3.43. Brahms, Piano Trio op. 8/

- Page 222: The number of signs introduced duri

- Page 226: NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 99

- Page 230: NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 10

- Page 234: separation between notes would also

- Page 238: Ex. 3.54. Schumann, Album für die

- Page 242: NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 10

- Page 246: NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMICS 10

- Page 250: Ex. 3.63. Haydn, Symphony no. 104/i

- Page 254: Ex. 3.66. Meyerbeer, Les Huguenots,

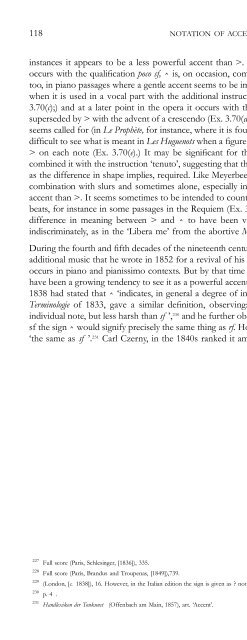

- Page 258: occurs not only in piano contexts,

- Page 262: stronger attack followed immediatel

- Page 268: 120 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 272: 122 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 276: 124 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 280: 126 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 284: 128 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 288: 130 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 292: 132 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 296: 134 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 300: 136 NOTATION OF ACCENTS AND DYNAMIC

- Page 304: 4 Articulation and Phrasing Just as

- Page 308: 140 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING expre

- Page 312: 142 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING deliv

- Page 316:

144 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING he ag

- Page 320:

146 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING symme

- Page 324:

148 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING evide

- Page 328:

150 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 332:

152 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 336:

154 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 340:

156 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 344:

158 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING ‘ei

- Page 348:

160 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING movem

- Page 352:

162 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 356:

164 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING Ex. 4

- Page 360:

166 ARTICULATION AND PHRASING the p

- Page 364:

5 Articulation and Expression The i

- Page 368:

170 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION In

- Page 372:

172 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Tow

- Page 376:

174 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION A c

- Page 380:

176 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 384:

178 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION The

- Page 388:

180 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 392:

182 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION amb

- Page 396:

184 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 400:

186 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 404:

188 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 408:

190 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 412:

192 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 416:

194 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION Ex.

- Page 420:

196 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION pra

- Page 424:

198 ARTICULATION AND EXPRESSION str

- Page 428:

6 The Notation of Articulation and

- Page 432:

202 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 436:

204 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 440:

206 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 444:

208 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 448:

210 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 452:

212 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 456:

214 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 460:

216 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 464:

218 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 468:

220 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 472:

222 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 476:

224 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 480:

226 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 484:

228 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 488:

230 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 492:

232 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 496:

234 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 500:

236 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 504:

238 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 508:

240 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 512:

242 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 516:

244 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 520:

246 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 524:

248 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 528:

250 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 532:

252 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 536:

254 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 540:

256 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 544:

258 NOTATION OF ARTICULATION AND PH

- Page 548:

260 STRING BOWING FIG. 7.1. Woldema

- Page 552:

262 STRING BOWING were many accepte

- Page 556:

264 STRING BOWING Ex. 7.2. (a) Picc

- Page 560:

266 STRING BOWING Ex. 7.2.cont.

- Page 564:

268 STRING BOWING Dictionary of Mus

- Page 568:

270 STRING BOWING requires the same

- Page 572:

272 STRING BOWING were still oppose

- Page 576:

274 STRING BOWING extremely exact.

- Page 580:

276 STRING BOWING From this and oth

- Page 584:

278 STRING BOWING style was modifie

- Page 588:

280 STRING BOWING often, one violin

- Page 592:

8 Tempo Historical evidence and con

- Page 596:

284 TEMPO tempo when once taken, he

- Page 600:

286 TEMPO Presto of the fourth move

- Page 604:

288 TEMPO different traditions ofte

- Page 608:

290 TEMPO Late Eighteenth-Century a

- Page 612:

292 TEMPO (particularly in England

- Page 616:

294 TEMPO In his discussion of 2/4,

- Page 620:

296 TEMPO the so-called chamber sty

- Page 624:

298 TEMPO 1791. 556 Comparison of T

- Page 628:

300 TEMPO assumes that, in general,

- Page 632:

302 TEMPO Table 8.4. Beethoven's Me

- Page 636:

304 TEMPO courtly dances, the yards

- Page 640:

306 TEMPO Ex. 8.1.Hummel, A Complet

- Page 644:

308 TEMPO Ex. 8.3.Hummel, A Complet

- Page 648:

310 TEMPO fast as smaller notes in

- Page 652:

312 TEMPO composer. We are not accu

- Page 656:

314 ALLA BREVE same problem bedevil

- Page 660:

316 ALLA BREVE true value and is on

- Page 664:

318 ALLA BREVE mixture of antiquari

- Page 668:

320 ALLA BREVE striking. It is like

- Page 672:

322 ALLA BREVE cases, however, move

- Page 676:

324 ALLA BREVE Table 9.2. The Relat

- Page 680:

326 ALLA BREVE Table 9.3. The Relat

- Page 684:

328 ALLA BREVE Table 9.4. The Relat

- Page 688:

330 ALLA BREVE Table 9.5. The Relat

- Page 692:

332 ALLA BREVE R11b Un poco lento

- Page 696:

334 ALLA BREVE passionato ? = 84 ?

- Page 700:

10 Tempo Terms As the connotations

- Page 704:

338 TEMPO TERMS derive from them, h

- Page 708:

340 TEMPO TERMS mark, a tempo term,

- Page 712:

342 TEMPO TERMS Not all musicians,

- Page 716:

344 TEMPO TERMS of semiquavers than

- Page 720:

346 TEMPO TERMS The metronome marks

- Page 724:

348 TEMPO TERMS Ex. 10.1.cont. (b)

- Page 728:

350 TEMPO TERMS ‘andante con moto

- Page 732:

352 TEMPO TERMS slower than ‘anda

- Page 736:

354 TEMPO TERMS In Rossini's music,

- Page 740:

356 TEMPO TERMS than that indicated

- Page 744:

358 TEMPO TERMS gave metronome mark

- Page 748:

360 TEMPO TERMS and usually regarde

- Page 752:

362 TEMPO TERMS note a small gap oc

- Page 756:

364 TEMPO TERMS Maestoso Löhlein c

- Page 760:

366 TEMPO TERMS Allegretto Reichard

- Page 764:

368 TEMPO TERMS useful to consider

- Page 768:

370 TEMPO TERMS there was a very ma

- Page 772:

372 TEMPO TERMS seem faster. Wagner

- Page 776:

374 TEMPO TERMS Cantabile ‘Cantab

- Page 780:

376 TEMPO MODIFICATION certain spec

- Page 784:

378 TEMPO MODIFICATION (b) There ca

- Page 788:

380 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.2. T

- Page 792:

382 TEMPO MODIFICATION remarking th

- Page 796:

384 TEMPO MODIFICATION a nicety in

- Page 800:

386 TEMPO MODIFICATION the middle c

- Page 804:

388 TEMPO MODIFICATION regards regu

- Page 808:

390 TEMPO MODIFICATION surpasses it

- Page 812:

392 TEMPO MODIFICATION noted for hi

- Page 816:

394 TEMPO MODIFICATION Conservatoir

- Page 820:

396 TEMPO MODIFICATION Modication o

- Page 824:

398 TEMPO MODIFICATION Türk had st

- Page 828:

400 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.8. (a

- Page 832:

402 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.9.con

- Page 836:

404 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.9.con

- Page 840:

406 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.12. B

- Page 844:

408 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.14.co

- Page 848:

410 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.16.co

- Page 852:

412 TEMPO MODIFICATION Ex. 11.17. C

- Page 856:

414 TEMPO MODIFICATION case, like a

- Page 860:

416 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 864:

418 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 868:

420 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 872:

422 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 876:

424 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 880:

426 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 884:

428 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 888:

430 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 892:

432 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 896:

434 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 900:

436 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 904:

438 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 908:

440 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 912:

442 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 916:

444 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 920:

446 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 924:

448 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 928:

450 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 932:

452 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 936:

454 EMBELLISHMENT, ORNAMENTATION, I

- Page 940:

456 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS fo

- Page 944:

458 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 948:

460 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS th

- Page 952:

462 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS 6)

- Page 956:

464 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS On

- Page 960:

466 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 964:

468 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 968:

470 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS De

- Page 972:

472 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 976:

474 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 980:

476 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS co

- Page 984:

478 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 988:

480 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 992:

482 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 996:

484 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1000:

486 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS sl

- Page 1004:

488 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1008:

490 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Fr

- Page 1012:

492 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS st

- Page 1016:

494 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS

- Page 1020:

496 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Jo

- Page 1024:

498 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS fi

- Page 1028:

500 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1032:

502 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1036:

504 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS fa

- Page 1040:

506 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1044:

508 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1048:

510 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1052:

512 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1056:

514 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS Ex

- Page 1060:

516 APPOGGIATURAS, TRILLS, TURNS wh

- Page 1064:

518 VIBRATO also have been applied

- Page 1068:

520 VIBRATO Ex. 14.2.Lussy, Musical

- Page 1072:

522 VIBRATO vibrato in singing (for

- Page 1076:

524 VIBRATO Studies of wind instrum

- Page 1080:

526 VIBRATO whether the adagio is p

- Page 1084:

528 VIBRATO Such views, though perh

- Page 1088:

530 VIBRATO gives the sound of the

- Page 1092:

532 VIBRATO by this great fault. Th

- Page 1096:

534 VIBRATO At about the same time

- Page 1100:

536 VIBRATO have sounded quite diff

- Page 1104:

538 VIBRATO most solo players. 1023

- Page 1108:

540 VIBRATO Ex. 14.9.Lasser, Vollst

- Page 1112:

542 VIBRATO mentioned. For the flut

- Page 1116:

544 VIBRATO flute methods. It is di

- Page 1120:

546 VIBRATO Indications of a change

- Page 1124:

548 VIBRATO Ex. 14.20.Löhlein, Anw

- Page 1128:

550 VIBRATO and in his later flute

- Page 1132:

552 VIBRATO Ex. 14.27.Baillot, L'Ar

- Page 1136:

554 VIBRATO would have been expecte

- Page 1140:

556 VIBRATO Ex. 14.33.Weber, Der Fr

- Page 1144:

15 Portamento The term ‘portament

- Page 1148:

560 PORTAMENTO Whatever the words u

- Page 1152:

562 PORTAMENTO like the Bourgeois G

- Page 1156:

564 PORTAMENTO And he went on to ad

- Page 1160:

566 PORTAMENTO and close parallels

- Page 1164:

568 PORTAMENTO Not only could the

- Page 1168:

570 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.10.García, N

- Page 1172:

572 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.13.Bériot, M

- Page 1176:

574 PORTAMENTO This ornament is eff

- Page 1180:

576 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.17.Dotzauer,

- Page 1184:

578 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.21.Spohr, Vio

- Page 1188:

580 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.25.Bériot, M

- Page 1192:

582 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.28.Meyerbeer,

- Page 1196:

584 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.34.Berwald Vi

- Page 1200:

586 PORTAMENTO Ex. 15.37.cont. Towa

- Page 1204:

The Fermata 16 Paralipomena The fer

- Page 1208:

590 PARALIPOMENA 1. ‘Each embelli

- Page 1212:

592 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.4. D. Corri

- Page 1216:

594 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.7. Haydn, S

- Page 1220:

596 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.10. Weber,

- Page 1224:

598 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.12. HÄser,

- Page 1228:

600 PARALIPOMENA The recitatives of

- Page 1232:

602 PARALIPOMENA keyboard instrumen

- Page 1236:

604 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.18. Meyerbe

- Page 1240:

606 PARALIPOMENA he implied that or

- Page 1244:

608 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.20. Meyerbe

- Page 1248:

610 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.22. Clement

- Page 1252:

612 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.24. P. A. C

- Page 1256:

614 PARALIPOMENA written equal pair

- Page 1260:

616 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.30. Haydn,

- Page 1264:

618 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.34. Schuber

- Page 1268:

620 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.35.cont. fi

- Page 1272:

622 PARALIPOMENA Violinspielen posi

- Page 1276:

624 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.41. Mozart,

- Page 1280:

626 PARALIPOMENA Ex. 16.43. Schuber

- Page 1284:

628 PARALIPOMENA of its systematize

- Page 1288:

630 PARALIPOMENA [Takttheile] (beat

- Page 1292:

632 PARALIPOMENA musicians might se

- Page 1296:

634 BIBLIOGRAPHY AUER, LEOPOLD, Vio

- Page 1300:

636 BIBLIOGRAPHY CRUTCHFIELD, WILL,

- Page 1304:

638 BIBLIOGRAPHY HABENECK, FRANÇOI

- Page 1308:

640 BIBLIOGRAPHY MARTIN, DAVID, ‘

- Page 1312:

642 BIBLIOGRAPHY SASLOV ISIDOR, ‘

- Page 1316:

644 BIBLIOGRAPHY WEIPPERT, JOHN ERH

- Page 1320:

646 INDEX appogiando , seearpeggiat

- Page 1324:

648 INDEX cadenza 158, 420, 543, 54

- Page 1328:

650 INDEX fermata ; pause 588, 591;

- Page 1332:

652 INDEX Joachim, Joseph 258, 268,

- Page 1336:

654 INDEX mezza voce 61 mezzo forte

- Page 1340:

656 INDEX portato 129, 130, 131, 20

- Page 1344:

658 INDEX Schumann, Robert Alexande

- Page 1348:

660 INDEX terms of tempo and expres

- Page 1352:

662 INDEX Weber, Carl Maria von ; E