Neil D. Burgess, Paul Harrison, Peter Sumbi, James Laizer, Adam ...

Neil D. Burgess, Paul Harrison, Peter Sumbi, James Laizer, Adam ...

Neil D. Burgess, Paul Harrison, Peter Sumbi, James Laizer, Adam ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MANAGEMENT ISSUES: TANZANIA’S COASTAL FORESTS 2011<br />

The soils under the remaining patches of lowland forest are more fertile than those of surrounding<br />

woodlands and hence face pressure to be converted for agriculture. Growing population pressures also<br />

tend to decrease the length of fallow periods. Plantations of coconut, sisal and cashew nut also occupy<br />

considerable areas of coastal land, replacing lowland Coastal Forest and other natural habitats.<br />

A newly emerging threat is the establishment of large industrial plantations for the production of<br />

biofuels on the eastern African coast. Large areas of woodland and coastal forest habitats have already<br />

been cleared for Jatropha production in Kilwa District and around Pugu close to Dar es Salaam, and<br />

sugar cane plantations are also planned for the Bagamoyo area. Land allocation for plantations of trees<br />

is also being explored in southern Tanzania, through Green Resources, and there are also major<br />

development plans for agriculture in southern Tanzania, with potential for huge amounts of inward<br />

investment. These kinds of agricultural developments are proceeding rapidly and have the potential to<br />

transform the coastal region of Tanzania. In particular these developments have the potential to split<br />

the remaining migration corridors between the reserved patches of forest in many of coastal districts.<br />

4.4.2 Charcoal production<br />

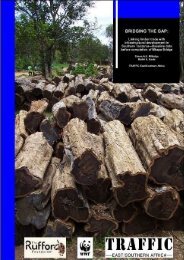

Charcoal production is a major cause of habitat loss in areas close to large cities and alongside main<br />

roads, particularly in Tanzania. Although not well quantified, the business of charcoal production has<br />

heavily impacted forest areas up to 200 kilometres from Dar-es-Salaam, and is spreading ever further<br />

into the bush. Away from towns and roads this threat is much less important as local people use<br />

firewood for cooking and transport difficulties discourage charcoal production as a cash crop. The major<br />

supply routes of charcoal to Dar es Salaam are along the Kilwa, Morogoro and Pugu roads; with the<br />

Kilwa road accounting for 50% of the total supply – much of this being sourced from the forests and<br />

woodlands up to 150 km distance from Dar es Salaam (Ahrends 2005; Ahrends et al. 2010).<br />

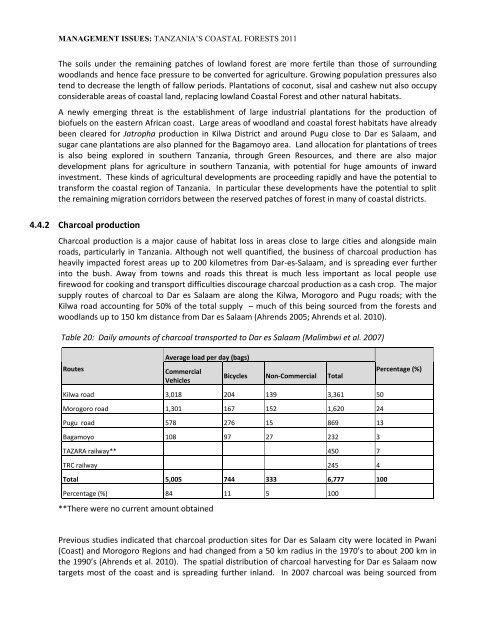

Table 20: Daily amounts of charcoal transported to Dar es Salaam (Malimbwi et al. 2007)<br />

Routes<br />

Average load per day (bags)<br />

Commercial<br />

Vehicles<br />

Bicycles Non-Commercial Total<br />

Kilwa road 3,018 204 139 3,361 50<br />

Morogoro road 1,301 167 152 1,620 24<br />

Pugu road 578 276 15 869 13<br />

Bagamoyo 108 97 27 232 3<br />

TAZARA railway** 450 7<br />

TRC railway 245 4<br />

Total 5,005 744 333 6,777 100<br />

Percentage (%) 84 11 5 100<br />

**There were no current amount obtained<br />

Percentage (%)<br />

Previous studies indicated that charcoal production sites for Dar es Salaam city were located in Pwani<br />

(Coast) and Morogoro Regions and had changed from a 50 km radius in the 1970’s to about 200 km in<br />

the 1990’s (Ahrends et al. 2010). The spatial distribution of charcoal harvesting for Dar es Salaam now<br />

targets most of the coast and is spreading further inland. In 2007 charcoal was being sourced from