The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

• 140 • W.S.Hanson<br />

eventually settling down in<br />

permanent fortresses at York,<br />

Caerleon and Chester. <strong>The</strong> bulk <strong>of</strong><br />

the military garrison, however, was<br />

made up <strong>of</strong> auxiliary troops,<br />

including <strong>ca</strong>valry, sub-divided into<br />

units approximately 500 or 1,000<br />

strong. <strong>The</strong>se were non-citizen<br />

soldiers, recruited <strong>from</strong> the<br />

provinces <strong>of</strong> the Empire, who<br />

formed the main front-line and<br />

garrison troops. <strong>The</strong>y were housed<br />

in forts that varied in size<br />

considerably <strong>from</strong> 0.8 to 4 ha in<br />

internal area (Figure 8.5). Three<br />

examples (Elginhaugh, Housesteads<br />

and Vindolanda) are described<br />

below. Indeed, there is still much<br />

debate about the relationship<br />

between auxiliary fort sizes and the<br />

different types <strong>of</strong> unit known,<br />

particularly in relation to the<br />

housing <strong>of</strong> <strong>ca</strong>valry horses inside or<br />

outside the fort. What is becoming<br />

increasingly clear, however, is that<br />

there is no simple correlation<br />

between auxiliary unit and fort, with<br />

units being split between different<br />

forts and/or different units<br />

occupying the same fort. <strong>The</strong><br />

division <strong>of</strong> units is further attested<br />

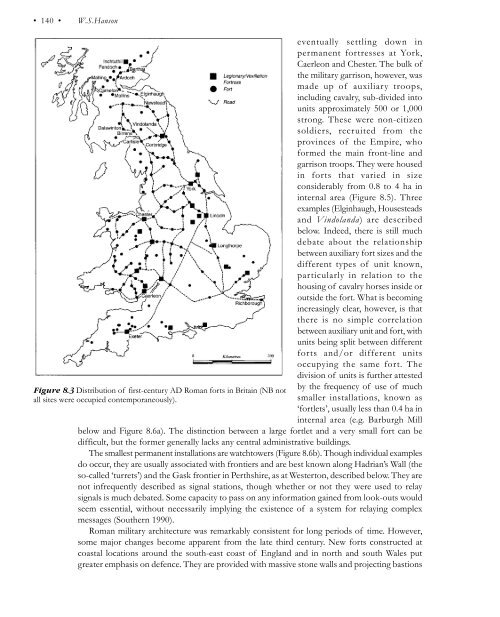

Figure 8.3 Distribution <strong>of</strong> first-century AD Roman forts in <strong>Britain</strong> (NB not<br />

by the frequency <strong>of</strong> use <strong>of</strong> much<br />

all sites were occupied contemporaneously).<br />

smaller installations, known as<br />

‘fortlets’, usually less than 0.4 ha in<br />

internal area (e.g. Barburgh Mill<br />

below and Figure 8.6a). <strong>The</strong> distinction between a large fortlet and a very small fort <strong>ca</strong>n be<br />

difficult, but the former generally lacks any central administrative buildings.<br />

<strong>The</strong> smallest permanent installations are watchtowers (Figure 8.6b). Though individual examples<br />

do occur, they are usually associated with frontiers and are best known along Hadrian’s Wall (the<br />

so-<strong>ca</strong>lled ‘turrets’) and the Gask frontier in Perthshire, as at Westerton, described below. <strong>The</strong>y are<br />

not infrequently described as signal stations, though whether or not they were used to relay<br />

signals is much debated. Some <strong>ca</strong>pacity to pass on any information gained <strong>from</strong> look-outs would<br />

seem essential, without necessarily implying the existence <strong>of</strong> a system for relaying complex<br />

messages (Southern 1990).<br />

Roman military architecture was remarkably consistent for long periods <strong>of</strong> time. However,<br />

some major changes become apparent <strong>from</strong> the late third century. New forts constructed at<br />

coastal lo<strong>ca</strong>tions around the south-east coast <strong>of</strong> England and in north and south Wales put<br />

greater emphasis on defence. <strong>The</strong>y are provided with massive stone walls and projecting bastions

![SS Sir Francis [+1917] - waughfamily.ca](https://img.yumpu.com/49438251/1/190x245/ss-sir-francis-1917-waughfamilyca.jpg?quality=85)