The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Middle Ages: rural settlement and manors<br />

• 255 •<br />

arable effort in the twelfth and<br />

thirteenth centuries was directed<br />

towards the cultivation <strong>of</strong> oats<br />

(Avena sp.). Such a fact is <strong>of</strong>ten (as<br />

there) already known <strong>from</strong> the<br />

documentary evidence, and what is<br />

more exciting is the unique<br />

opportunity such finds present <strong>of</strong><br />

assessing the quality <strong>of</strong> medieval<br />

crops (Bell 1989).<br />

Manor houses themselves have<br />

been studied by archaeologists<br />

through ex<strong>ca</strong>vation, by architectural<br />

historians who have looked at<br />

standing examples, and by<br />

historians using documents, usually<br />

financial accounts <strong>of</strong> construction<br />

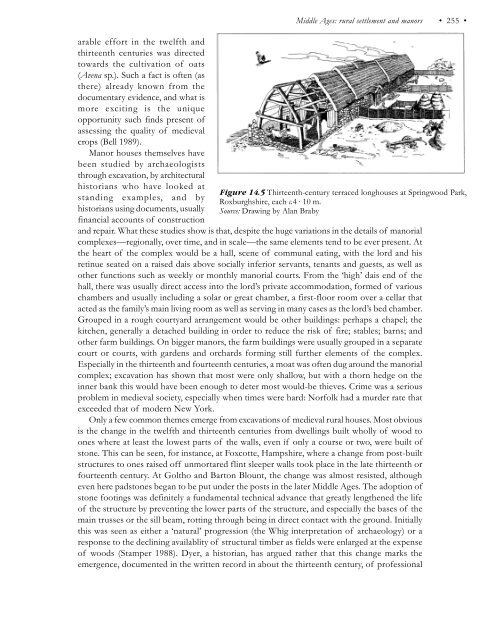

Figure 14.5 Thirteenth-century terraced longhouses at Springwood Park,<br />

Roxburghshire, each c.4 · 10 m.<br />

Source: Drawing by Alan Braby<br />

and repair. What these studies show is that, despite the huge variations in the details <strong>of</strong> manorial<br />

complexes—regionally, over time, and in s<strong>ca</strong>le—the same elements tend to be ever present. At<br />

the heart <strong>of</strong> the complex would be a hall, scene <strong>of</strong> communal eating, with the lord and his<br />

retinue seated on a raised dais above socially inferior servants, tenants and guests, as well as<br />

other functions such as weekly or monthly manorial courts. From the ‘high’ dais end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hall, there was usually direct access into the lord’s private accommodation, formed <strong>of</strong> various<br />

chambers and usually including a solar or great chamber, a first-floor room over a cellar that<br />

acted as the family’s main living room as well as serving in many <strong>ca</strong>ses as the lord’s bed chamber.<br />

Grouped in a rough courtyard arrangement would be other buildings: perhaps a chapel; the<br />

kitchen, generally a detached building in order to reduce the risk <strong>of</strong> fire; stables; barns; and<br />

other farm buildings. On bigger manors, the farm buildings were usually grouped in a separate<br />

court or courts, with gardens and orchards forming still further elements <strong>of</strong> the complex.<br />

Especially in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a moat was <strong>of</strong>ten dug around the manorial<br />

complex; ex<strong>ca</strong>vation has shown that most were only shallow, but with a thorn hedge on the<br />

inner bank this would have been enough to deter most would-be thieves. Crime was a serious<br />

problem in medieval society, especially when times were hard: Norfolk had a murder rate that<br />

exceeded that <strong>of</strong> modern New York.<br />

Only a few common themes emerge <strong>from</strong> ex<strong>ca</strong>vations <strong>of</strong> medieval rural houses. Most obvious<br />

is the change in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries <strong>from</strong> dwellings built wholly <strong>of</strong> wood to<br />

ones where at least the lowest parts <strong>of</strong> the walls, even if only a course or two, were built <strong>of</strong><br />

stone. This <strong>ca</strong>n be seen, for instance, at Foxcotte, Hampshire, where a change <strong>from</strong> post-built<br />

structures to ones raised <strong>of</strong>f unmortared flint sleeper walls took place in the late thirteenth or<br />

fourteenth century. At Goltho and Barton Blount, the change was almost resisted, although<br />

even here padstones began to be put under the posts in the later Middle Ages. <strong>The</strong> adoption <strong>of</strong><br />

stone footings was definitely a fundamental techni<strong>ca</strong>l advance that greatly lengthened the life<br />

<strong>of</strong> the structure by preventing the lower parts <strong>of</strong> the structure, and especially the bases <strong>of</strong> the<br />

main trusses or the sill beam, rotting through being in direct contact with the ground. Initially<br />

this was seen as either a ‘natural’ progression (the Whig interpretation <strong>of</strong> archaeology) or a<br />

response to the declining availablity <strong>of</strong> structural timber as fields were enlarged at the expense<br />

<strong>of</strong> woods (Stamper 1988). Dyer, a historian, has argued rather that this change marks the<br />

emergence, documented in the written record in about the thirteenth century, <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional

![SS Sir Francis [+1917] - waughfamily.ca](https://img.yumpu.com/49438251/1/190x245/ss-sir-francis-1917-waughfamilyca.jpg?quality=85)