The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

• 232 • Roberta Gilchrist<br />

multiple churches might result, such<br />

as at Beechamwell, Norfolk, where<br />

the convergence <strong>of</strong> three settlements<br />

resulted in the co-existence <strong>of</strong> three<br />

parish churches in a single village. In<br />

eastern England, <strong>ca</strong>ses <strong>of</strong> multiple<br />

lordship oc<strong>ca</strong>sionally resulted in the<br />

sharing <strong>of</strong> a single churchyard by two<br />

to three parish churches, such as at<br />

Reepham, Norfolk. In regions <strong>of</strong><br />

dispersed settlement, churches may<br />

have been founded in relative<br />

isolation, although this appearance<br />

may sometimes be deceptive.<br />

Agricultural shifts, such as a<br />

transition <strong>from</strong> arable to pastoral<br />

farming, could <strong>ca</strong>use the movement<br />

<strong>of</strong> settlement to areas <strong>of</strong> free<br />

grazing, such as greens and parish<br />

boundaries. In such <strong>ca</strong>ses, early<br />

village sites were deserted and<br />

churches that now appear to be<br />

isolated in the lands<strong>ca</strong>pe were once<br />

in close proximity to their<br />

communities. Churches in towns<br />

were placed in order to encourage<br />

easy access: on street corners, on<br />

main thoroughfares, at markets,<br />

bridges and at gates in town walls,<br />

so that travellers and pilgrims could<br />

visit them easily when beginning or<br />

completing a journey.<br />

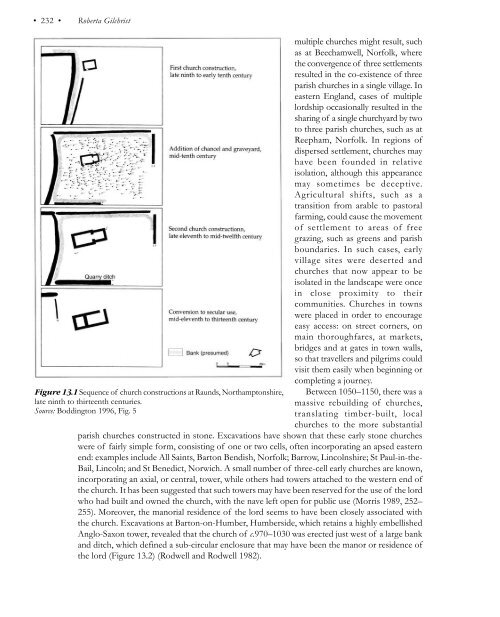

Figure 13.1 Sequence <strong>of</strong> church constructions at Raunds, Northamptonshire, Between 1050–1150, there was a<br />

late ninth to thirteenth centuries.<br />

massive rebuilding <strong>of</strong> churches,<br />

Source: Boddington 1996, Fig. 5<br />

translating timber-built, lo<strong>ca</strong>l<br />

churches to the more substantial<br />

parish churches constructed in stone. Ex<strong>ca</strong>vations have shown that these early stone churches<br />

were <strong>of</strong> fairly simple form, consisting <strong>of</strong> one or two cells, <strong>of</strong>ten incorporating an apsed eastern<br />

end: examples include All Saints, Barton Bendish, Norfolk; Barrow, Lincolnshire; St Paul-in-the-<br />

Bail, Lincoln; and St Benedict, Norwich. A small number <strong>of</strong> three-cell early churches are known,<br />

incorporating an axial, or central, tower, while others had towers attached to the western end <strong>of</strong><br />

the church. It has been suggested that such towers may have been reserved for the use <strong>of</strong> the lord<br />

who had built and owned the church, with the nave left open for public use (Morris 1989, 252–<br />

255). Moreover, the manorial residence <strong>of</strong> the lord seems to have been closely associated with<br />

the church. Ex<strong>ca</strong>vations at Barton-on-Humber, Humberside, which retains a highly embellished<br />

<strong>An</strong>glo-Saxon tower, revealed that the church <strong>of</strong> c.970–1030 was erected just west <strong>of</strong> a large bank<br />

and ditch, which defined a sub-circular enclosure that may have been the manor or residence <strong>of</strong><br />

the lord (Figure 13.2) (Rodwell and Rodwell 1982).

![SS Sir Francis [+1917] - waughfamily.ca](https://img.yumpu.com/49438251/1/190x245/ss-sir-francis-1917-waughfamilyca.jpg?quality=85)