- Page 2 and 3: A Dictionary of Linguistics and Pho

- Page 4 and 5: A Dictionary of Linguistics and Pho

- Page 6 and 7: Contents Preface to the Sixth Editi

- Page 8 and 9: Preface to the Sixth Edition vii di

- Page 10 and 11: Preface to the Sixth Edition ix lan

- Page 12 and 13: Acknowledgements For the first edit

- Page 14 and 15: List of Abbreviations Term Gloss Re

- Page 16 and 17: List of Abbreviations xv DAF delaye

- Page 18 and 19: List of Abbreviations xvii IE Indo-

- Page 20 and 21: List of Abbreviations xix part, PAR

- Page 22 and 23: List of Abbreviations xxi UTAH unif

- Page 24 and 25: List of Symbols xxiii * asterisk; s

- Page 26 and 27: The International Phonetic Alphabet

- Page 28 and 29: 2 A-binding abessive’) is found i

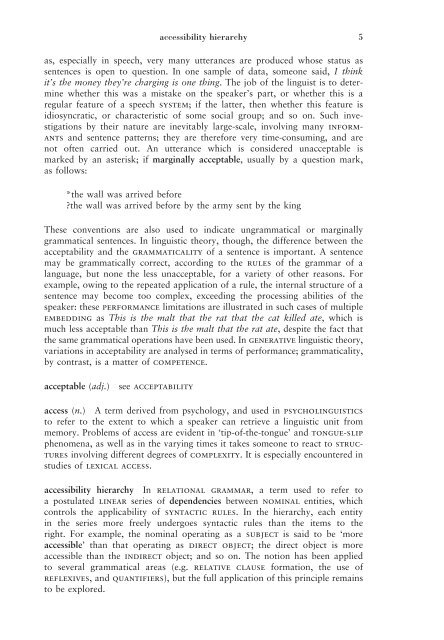

- Page 32 and 33: 6 accessible accessible (adj.) see

- Page 34 and 35: 8 acquire fundamental frequency of

- Page 36 and 37: 10 actualization actualization (n.)

- Page 38 and 39: 12 adjoin class in English (and sim

- Page 40 and 41: 14 adultocentric linguistic area. A

- Page 42 and 43: 16 affixal morphology are a type of

- Page 44 and 45: 18 AGR AGR /caìv/ see agreement ag

- Page 46 and 47: 20 allegro with illative, adessive

- Page 48 and 49: 22 alternative set usual symbol for

- Page 50 and 51: 24 anacoluthon greater the intensit

- Page 52 and 53: 26 anchor vowels are also known as

- Page 54 and 55: 28 antiformant (2) The term is also

- Page 56 and 57: 30 aphesis aphesis /cafvs}s/ (n.),

- Page 58 and 59: 32 appropriateness appropriateness

- Page 60 and 61: 34 arity other term to the predicat

- Page 62 and 63: 36 articulator model airflow throug

- Page 64 and 65: 38 aspect aspect (n.) (asp) A categ

- Page 66 and 67: 40 assimilatory Several types of as

- Page 68 and 69: 42 asymmetric rhythmic theory man d

- Page 70 and 71: 44 auditory phonetics and John MacD

- Page 72 and 73: 46 auxiliary linear arrangement of

- Page 74 and 75: B baby-talk (n.) see child-directed

- Page 76 and 77: 50 barrier barrier (n.) A term used

- Page 78 and 79: 52 benefactive anticipate the devel

- Page 80 and 81:

54 binarity binarity, binarism (n.)

- Page 82 and 83:

56 bivalent phones, and vice versa

- Page 84 and 85:

58 Bloomfieldianism Bloomfieldianis

- Page 86 and 87:

60 bow-wow theory bow-wow theory Th

- Page 88 and 89:

62 branching quantifiers branching

- Page 90 and 91:

C C An abbreviation in government-b

- Page 92 and 93:

66 caregiver/caretaker speech VOWEL

- Page 94 and 95:

68 cataphora used with an objective

- Page 96 and 97:

70 causative cause and effect leadi

- Page 98 and 99:

72 CHAIN (2) In government-binding

- Page 100 and 101:

74 checking in a short time interva

- Page 102 and 103:

76 Chomsky hierarchy and psychologi

- Page 104 and 105:

78 classification classification (n

- Page 106 and 107:

80 cline [!] formerly [t], and late

- Page 108 and 109:

82 coalesce in syllables in English

- Page 110 and 111:

84 cognise a cognate subject-verb-o

- Page 112 and 113:

86 collapse elements belonging to t

- Page 114 and 115:

88 comment term ‘command’, but

- Page 116 and 117:

90 communication science that langu

- Page 118 and 119:

92 competence lengthened when a syl

- Page 120 and 121:

94 complete assimilation complete a

- Page 122 and 123:

96 componential analysis the streng

- Page 124 and 125:

98 concatenate take into account th

- Page 126 and 127:

100 condition on extraction domains

- Page 128 and 129:

102 connection connection (n.) A te

- Page 130 and 131:

104 conspire conspire (v.) see cons

- Page 132 and 133:

106 constraint demotion algorithm L

- Page 134 and 135:

108 contact assimilation restricted

- Page 136 and 137:

110 contextualize semantics. Contex

- Page 138 and 139:

112 contrary that John has not gone

- Page 140 and 141:

114 conversational turn conversatio

- Page 142 and 143:

116 copula copula (n.) A term used

- Page 144 and 145:

118 corpus-internal/-external evide

- Page 146 and 147:

120 counter-agent much information.

- Page 148 and 149:

122 creativity such as Oh I don’t

- Page 150 and 151:

124 cross-sectional co-referential.

- Page 152 and 153:

126 cycle phrase-marker (the first

- Page 154 and 155:

D dangling participle In traditiona

- Page 156 and 157:

130 deadjectival such as ∃(e[hit(

- Page 158 and 159:

132 default default (n.) The applic

- Page 160 and 161:

134 delayed delayed (adj.) One of t

- Page 162 and 163:

136 denotation example, in the gard

- Page 164 and 165:

138 dependent relation holds betwee

- Page 166 and 167:

140 descriptive adequacy/grammar/li

- Page 168 and 169:

142 diachronic [ai] etc.; a diamorp

- Page 170 and 171:

144 dialectalization particular pro

- Page 172 and 173:

146 diphthong has also been called

- Page 174 and 175:

148 discourse argues that languages

- Page 176 and 177:

150 disharmony signal can be analys

- Page 178 and 179:

152 distinctiveness for particular

- Page 180 and 181:

154 distributed representation dist

- Page 182 and 183:

156 donkey sentence and N are direc

- Page 184 and 185:

158 downward entailing generally as

- Page 186 and 187:

160 dynamic linguistics/phonetics/p

- Page 188 and 189:

162 ecological linguistics cultural

- Page 190 and 191:

164 egressive egressive (adj.) A te

- Page 192 and 193:

166 elision elision (n.) A term use

- Page 194 and 195:

168 empiricism empiricism (n.) An a

- Page 196 and 197:

170 entrench follows from (is entai

- Page 198 and 199:

172 equi NP deletion equative sente

- Page 200 and 201:

174 état de langue the increased u

- Page 202 and 203:

176 evaluative (periodicity), such

- Page 204 and 205:

178 exhaustiveness phonetics, the a

- Page 206 and 207:

180 exponence exponence (n.) A conc

- Page 208 and 209:

182 extralinguistic it is possible

- Page 210 and 211:

F face (n.) In pragmatics and inter

- Page 212 and 213:

186 fatherese remote degree of rela

- Page 214 and 215:

188 felicity conditions felicity co

- Page 216 and 217:

190 finite automata independent sen

- Page 218 and 219:

192 flat flat (adj.) (1) A term use

- Page 220 and 221:

194 FOOTBIN FOOTBIN (n.) In optimal

- Page 222 and 223:

196 formant formant (n.) (F) A term

- Page 224 and 225:

198 free used to specify the range

- Page 226 and 227:

200 front /r/ is often articulated

- Page 228 and 229:

202 functional application/composit

- Page 230 and 231:

204 fusion component in a complex s

- Page 232 and 233:

206 gemination gemination (n.) A te

- Page 234 and 235:

208 generalized quantifier theory s

- Page 236 and 237:

210 genitive genitive (adj./n.) (ge

- Page 238 and 239:

212 gliding vowel gliding vowel see

- Page 240 and 241:

214 goal different university centr

- Page 242 and 243:

216 government theory government an

- Page 244 and 245:

218 grammar induction term traditio

- Page 246 and 247:

220 grapheme grapheme (n.) The mini

- Page 248 and 249:

222 ground noun ground noun see gri

- Page 250 and 251:

224 hapax legomenon hapax legomenon

- Page 252 and 253:

226 head-driven phrase-structure gr

- Page 254 and 255:

228 hiatus heuristic’), and used

- Page 256 and 257:

230 hodiernal linguistic data; oppo

- Page 258 and 259:

232 horizontal grouping/splitting h

- Page 260 and 261:

I iamb (n.) A traditional term in m

- Page 262 and 263:

236 idiom idiom (n.) A term used in

- Page 264 and 265:

238 imperfect tense imperfect tense

- Page 266 and 267:

240 inclusive given an excluding in

- Page 268 and 269:

242 indicative has come to be known

- Page 270 and 271:

244 inflectional language (2) (INFL

- Page 272 and 273:

246 inheritance inheritance (n.) A

- Page 274 and 275:

248 instrumental and business. As o

- Page 276 and 277:

250 interlingua view, phonology wou

- Page 278 and 279:

252 interruptibility interruptibili

- Page 280 and 281:

254 invariable in generative gramma

- Page 282 and 283:

256 isogloss intervals throughout a

- Page 284 and 285:

J Jakobsonian (adj.) Characteristic

- Page 286 and 287:

K Katz-Postal hypothesis A proposed

- Page 288 and 289:

262 knowledge about language knowle

- Page 290 and 291:

264 labio-velar for a labio-dental

- Page 292 and 293:

266 language acquisition device of

- Page 294 and 295:

268 language minority in the USA);

- Page 296 and 297:

270 last-cyclic rules former headin

- Page 298 and 299:

272 learning language can in princi

- Page 300 and 301:

274 lenis studied in terms of the n

- Page 302 and 303:

276 level-skipping level-skipping (

- Page 304 and 305:

278 lexical retrieval ‘types’ i

- Page 306 and 307:

280 lexotactics are used to simplif

- Page 308 and 309:

282 linear precedence rule linear p

- Page 310 and 311:

284 linguistics recent and rapid, h

- Page 312 and 313:

286 lip-rounding lip-rounding see r

- Page 314 and 315:

288 locus case form (‘a locative

- Page 316 and 317:

290 loopback follows the course of

- Page 318 and 319:

M macrolinguistics (n.) A term used

- Page 320 and 321:

294 manner adverb(ial) features, so

- Page 322 and 323:

296 marker sentences illustrate thi

- Page 324 and 325:

298 maximal-command The student who

- Page 326 and 327:

300 meaning construction the impera

- Page 328 and 329:

302 meronymy to as ‘phonemic spli

- Page 330 and 331:

304 metrical phonology L3 L2 L1 x t

- Page 332 and 333:

306 minimal free form of go is Mary

- Page 334 and 335:

308 mixing mixing (n.) M-level (n.)

- Page 336 and 337:

310 modifier modification-head-qual

- Page 338 and 339:

312 Montague grammar Montague gramm

- Page 340 and 341:

314 morpheme-based morphology morph

- Page 342 and 343:

316 morphotactics morphotactics (n.

- Page 344 and 345:

318 multilingual the same set of fe

- Page 346 and 347:

N narrative (adj./n.) An applicatio

- Page 348 and 349:

322 nativism it as a second or fore

- Page 350 and 351:

324 negative concord (as in French

- Page 352 and 353:

326 neurological linguistics neurol

- Page 354 and 355:

328 noise The notion has achieved s

- Page 356 and 357:

330 non-definite non-definite (adj.

- Page 358 and 359:

332 non-sexist language table. Such

- Page 360 and 361:

334 noun incorporation are often de

- Page 362 and 363:

O object (n.) (O, Obj, OBJ) A term

- Page 364 and 365:

338 obsolete previous era, such as

- Page 366 and 367:

340 open The structure is ill forme

- Page 368 and 369:

342 opposition opposition (n.) A te

- Page 370 and 371:

344 order is introduced, correspond

- Page 372 and 373:

346 overt The notion of complete ov

- Page 374 and 375:

348 palato-alveolar whole of the up

- Page 376 and 377:

350 parametric phonetics (2) See pa

- Page 378 and 379:

352 particle The name comes from th

- Page 380 and 381:

354 past perfect past perfect see p

- Page 382 and 383:

356 perception perception (n.) The

- Page 384 and 385:

358 peripheral at the next level, h

- Page 386 and 387:

360 phatic communion during which t

- Page 388 and 389:

362 phoneme have as few as fifteen

- Page 390 and 391:

364 phonetic setting reflects the a

- Page 392 and 393:

366 phonostylistics both of which r

- Page 394 and 395:

368 phylogeny generative device. Ph

- Page 396 and 397:

370 pitch meter also been applied t

- Page 398 and 399:

372 plethysmograph (2) In the study

- Page 400 and 401:

374 polysyllable large proportion o

- Page 402 and 403:

376 positive (e.g. unsuccessful can

- Page 404 and 405:

378 postvocalic postvocalic (adj.)

- Page 406 and 407:

380 Prague School to do with narrat

- Page 408 and 409:

382 predicate calculus fixed number

- Page 410 and 411:

384 prerequisites prerequisites (n.

- Page 412 and 413:

386 primitive primitive (adj./n.) A

- Page 414 and 415:

388 process procedures, of which th

- Page 416 and 417:

390 pro-form or pattern. A pattern

- Page 418 and 419:

392 prop relative pronouns, e.g. wh

- Page 420 and 421:

394 protasis unit, such as consonan

- Page 422 and 423:

396 psycholexicology interest, frig

- Page 424 and 425:

Q qualia structure /ckwe}l}v/, sing

- Page 426 and 427:

400 question produce such changes,

- Page 428 and 429:

402 rank classical TG subject-raisi

- Page 430 and 431:

404 reassociation taken together as

- Page 432 and 433:

406 recursively enumerable These ru

- Page 434 and 435:

408 referent referent (n.) A term u

- Page 436 and 437:

410 regular grammar the notion was

- Page 438 and 439:

412 relativized minimality relativi

- Page 440 and 441:

414 resonance resonance (n.) A term

- Page 442 and 443:

416 reversible reversible (adj.) se

- Page 444 and 445:

418 right dislocation right disloca

- Page 446 and 447:

420 root-and-pattern applies only t

- Page 448 and 449:

S S′ An abbreviation used in gene

- Page 450 and 451:

424 scansion by establishing four t

- Page 452 and 453:

426 segment segment (n.) A term use

- Page 454 and 455:

428 semanticity semanticity (n.) A

- Page 456 and 457:

430 semantic selection semantic sel

- Page 458 and 459:

432 semology that of a vowel; thoug

- Page 460 and 461:

434 serial relationship he will win

- Page 462 and 463:

436 sight translation a narrow, gro

- Page 464 and 465:

438 single-feature assimilation sin

- Page 466 and 467:

440 sluicing the sentence The child

- Page 468 and 469:

442 sonorant sonorant (adj./n.) (so

- Page 470 and 471:

444 space grammar (6) In the lingui

- Page 472 and 473:

446 speech act illocutionary force

- Page 474 and 475:

448 speech time acoustic or articul

- Page 476 and 477:

450 stability enriched by the inclu

- Page 478 and 479:

452 statistical universal the aim o

- Page 480 and 481:

454 stray system deals with an aspe

- Page 482 and 483:

456 stress-foot but in the phrase t

- Page 484 and 485:

458 structural ambiguity largely da

- Page 486 and 487:

460 stylistics stylistics (n.) A br

- Page 488 and 489:

462 subjective subjective (adj.) su

- Page 490 and 491:

464 substratum superiority, as can

- Page 492 and 493:

466 supplementary movements supplem

- Page 494 and 495:

468 syllable produce consonants. Th

- Page 496 and 497:

470 syndeton synchronically to refe

- Page 498 and 499:

472 synthesis examples: syntactical

- Page 500 and 501:

474 systematic phonetics systematic

- Page 502 and 503:

476 tactic the fact that their intu

- Page 504 and 505:

478 taxis relationship. Combination

- Page 506 and 507:

480 tensed Tense forms (i.e. variat

- Page 508 and 509:

482 text deixis the text in which t

- Page 510 and 511:

484 theolinguistics theolinguistics

- Page 512 and 513:

486 tonal polarity tonal polarity s

- Page 514 and 515:

488 tonogenesis on the meaning inte

- Page 516 and 517:

490 transcription literary excellen

- Page 518 and 519:

492 transformation (where be is a f

- Page 520 and 521:

494 transitivity transitivity (n.)

- Page 522 and 523:

496 triadic triadic (adj.) A term u

- Page 524 and 525:

498 truth value functions which map

- Page 526 and 527:

U ultimate constituent (UC) A term

- Page 528 and 529:

502 unfooted binary feature matrice

- Page 530 and 531:

504 universal universal (adj./n.) A

- Page 532 and 533:

506 uvular But it has proved very d

- Page 534 and 535:

508 valley valley (n.) see peak, sy

- Page 536 and 537:

510 velaric A loose auditory label

- Page 538 and 539:

512 vertical grouping/splitting wor

- Page 540 and 541:

514 vocal lips (2) In phonetics, a

- Page 542 and 543:

516 voice qualifier sometimes made

- Page 544 and 545:

518 vowel shift vowel shift see sou

- Page 546 and 547:

520 weak generative capacity weak g

- Page 548 and 549:

522 word different structural types

- Page 550 and 551:

524 word grammar In a more restrict

- Page 552 and 553:

526 X-tier X-tier (n.) A term used

- Page 554 and 555:

Z zero (adj./n.) A term used in som