Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

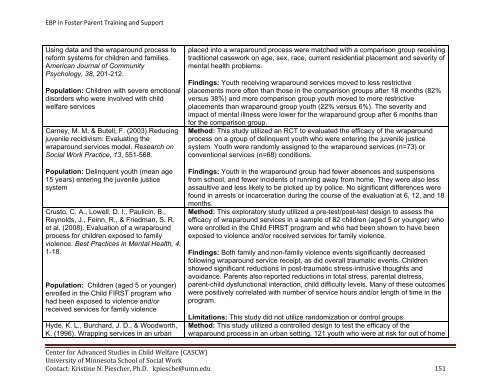

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>Us<strong>in</strong>g data <strong>and</strong> the wraparound process toreform systems for children <strong>and</strong> families.American Journal of CommunityPsychology, 38, 201-212.Population: Children with severe emotionaldisorders who were <strong>in</strong>volved with childwelfare servicesCarney, M. M, & Butell, F. (2003).Reduc<strong>in</strong>gjuvenile recidivism: Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g thewraparound services model. Research onSocial Work <strong>Practice</strong>, 13, 551-568.Population: Del<strong>in</strong>quent youth (mean age15 years) enter<strong>in</strong>g the juvenile justicesystemCrusto, C. A., Lowell, D. I., Paulic<strong>in</strong>, B.,Reynolds, J., Fe<strong>in</strong>n, R., & Friedman, S. R.et al. (2008). Evaluation of a wraparoundprocess for children exposed to familyviolence. Best <strong>Practice</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Mental Health, 4,1-18.Population: Children (aged 5 or younger)enrolled <strong>in</strong> the Child FIRST program whohad been exposed to violence <strong>and</strong>/orreceived services for family violenceHyde, K. L., Burchard, J. D., & Woodworth,K. (1996). Wrapp<strong>in</strong>g services <strong>in</strong> an urbanplaced <strong>in</strong>to a wraparound process were matched with a comparison group receiv<strong>in</strong>gtraditional casework on age, sex, race, current residential placement <strong>and</strong> severity ofmental health problems.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: Youth receiv<strong>in</strong>g wraparound services moved to less restrictiveplacements more often than those <strong>in</strong> the comparison groups after 18 months (82%versus 38%) <strong>and</strong> more comparison group youth moved to more restrictiveplacements than wraparound group youth (22% versus 6%). The severity <strong>and</strong>impact of mental illness were lower for the wraparound group after 6 months thanfor the comparison group.Method: This study utilized an RCT to evaluated the efficacy of the wraparoundprocess on a group of del<strong>in</strong>quent youth who were enter<strong>in</strong>g the juvenile justicesystem. Youth were r<strong>and</strong>omly assigned to the wraparound services (n=73) orconventional services (n=68) conditions.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: Youth <strong>in</strong> the wraparound group had fewer absences <strong>and</strong> suspensionsfrom school, <strong>and</strong> fewer <strong>in</strong>cidents of runn<strong>in</strong>g away from home. They were also lessassaultive <strong>and</strong> less likely to be picked up by police. No significant differences werefound <strong>in</strong> arrests or <strong>in</strong>carceration dur<strong>in</strong>g the course of the evaluation at 6, 12, <strong>and</strong> 18months.Method: This exploratory study utilized a pre-test/post-test design to assess theefficacy of wraparound services <strong>in</strong> a sample of 82 children (aged 5 or younger) whowere enrolled <strong>in</strong> the Child FIRST program <strong>and</strong> who had been shown to have beenexposed to violence <strong>and</strong>/or received services for family violence.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: Both family <strong>and</strong> non-family violence events significantly decreasedfollow<strong>in</strong>g wraparound service receipt, as did overall traumatic events. Childrenshowed significant reductions <strong>in</strong> post-traumatic stress-<strong>in</strong>trusive thoughts <strong>and</strong>avoidance. <strong>Parent</strong>s also reported reductions <strong>in</strong> total stress, parental distress,parent-child dysfunctional <strong>in</strong>teraction, child difficulty levels. Many of these outcomeswere positively correlated with number of service hours <strong>and</strong>/or length of time <strong>in</strong> theprogram.Limitations: This study did not utilize r<strong>and</strong>omization or control groups.Method: This study utilized a controlled design to test the efficacy of thewraparound process <strong>in</strong> an urban sett<strong>in</strong>g. 121 youth who were at risk for out of homeCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 151