Ten-Year Impacts of Burkina Faso’s BRIGHT Program

n?u=RePEc:mpr:mprres:2ecdd42bb503422b802ce20da2bf64b7&r=edu

n?u=RePEc:mpr:mprres:2ecdd42bb503422b802ce20da2bf64b7&r=edu

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

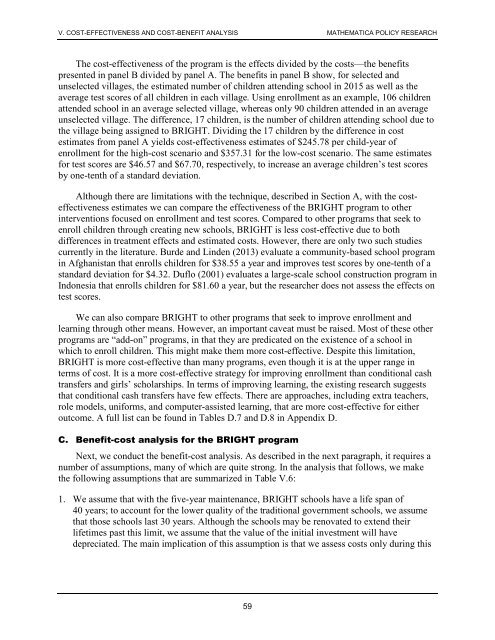

V. COST-EFFECTIVENESS AND COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH<br />

The cost-effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the program is the effects divided by the costs—the benefits<br />

presented in panel B divided by panel A. The benefits in panel B show, for selected and<br />

unselected villages, the estimated number <strong>of</strong> children attending school in 2015 as well as the<br />

average test scores <strong>of</strong> all children in each village. Using enrollment as an example, 106 children<br />

attended school in an average selected village, whereas only 90 children attended in an average<br />

unselected village. The difference, 17 children, is the number <strong>of</strong> children attending school due to<br />

the village being assigned to <strong>BRIGHT</strong>. Dividing the 17 children by the difference in cost<br />

estimates from panel A yields cost-effectiveness estimates <strong>of</strong> $245.78 per child-year <strong>of</strong><br />

enrollment for the high-cost scenario and $357.31 for the low-cost scenario. The same estimates<br />

for test scores are $46.57 and $67.70, respectively, to increase an average children’s test scores<br />

by one-tenth <strong>of</strong> a standard deviation.<br />

Although there are limitations with the technique, described in Section A, with the costeffectiveness<br />

estimates we can compare the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the <strong>BRIGHT</strong> program to other<br />

interventions focused on enrollment and test scores. Compared to other programs that seek to<br />

enroll children through creating new schools, <strong>BRIGHT</strong> is less cost-effective due to both<br />

differences in treatment effects and estimated costs. However, there are only two such studies<br />

currently in the literature. Burde and Linden (2013) evaluate a community-based school program<br />

in Afghanistan that enrolls children for $38.55 a year and improves test scores by one-tenth <strong>of</strong> a<br />

standard deviation for $4.32. Duflo (2001) evaluates a large-scale school construction program in<br />

Indonesia that enrolls children for $81.60 a year, but the researcher does not assess the effects on<br />

test scores.<br />

We can also compare <strong>BRIGHT</strong> to other programs that seek to improve enrollment and<br />

learning through other means. However, an important caveat must be raised. Most <strong>of</strong> these other<br />

programs are “add-on” programs, in that they are predicated on the existence <strong>of</strong> a school in<br />

which to enroll children. This might make them more cost-effective. Despite this limitation,<br />

<strong>BRIGHT</strong> is more cost-effective than many programs, even though it is at the upper range in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> cost. It is a more cost-effective strategy for improving enrollment than conditional cash<br />

transfers and girls’ scholarships. In terms <strong>of</strong> improving learning, the existing research suggests<br />

that conditional cash transfers have few effects. There are approaches, including extra teachers,<br />

role models, uniforms, and computer-assisted learning, that are more cost-effective for either<br />

outcome. A full list can be found in Tables D.7 and D.8 in Appendix D.<br />

C. Benefit-cost analysis for the <strong>BRIGHT</strong> program<br />

Next, we conduct the benefit-cost analysis. As described in the next paragraph, it requires a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> assumptions, many <strong>of</strong> which are quite strong. In the analysis that follows, we make<br />

the following assumptions that are summarized in Table V.6:<br />

1. We assume that with the five-year maintenance, <strong>BRIGHT</strong> schools have a life span <strong>of</strong><br />

40 years; to account for the lower quality <strong>of</strong> the traditional government schools, we assume<br />

that those schools last 30 years. Although the schools may be renovated to extend their<br />

lifetimes past this limit, we assume that the value <strong>of</strong> the initial investment will have<br />

depreciated. The main implication <strong>of</strong> this assumption is that we assess costs only during this<br />

59