From Page to Screen - WRAP: Warwick Research Archive Portal ...

From Page to Screen - WRAP: Warwick Research Archive Portal ...

From Page to Screen - WRAP: Warwick Research Archive Portal ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

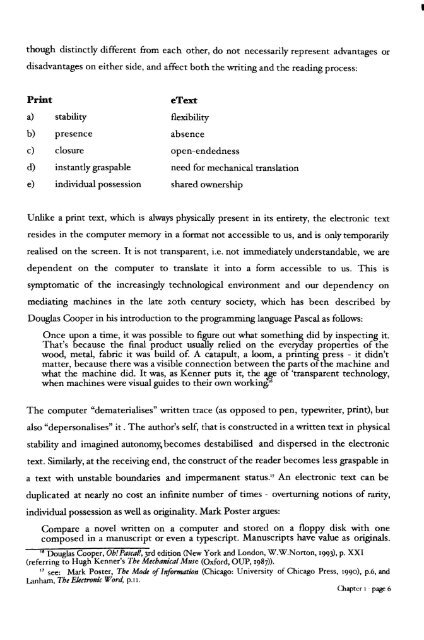

though distinctly different from each other, do not necessarily represent advantages or<br />

disadvantages on either side, and affect both the writing and the reading process:<br />

Print eText<br />

a) stability flexibility<br />

b) presence absence<br />

c) closure open-endedness<br />

d) instantlygraspable need for mechanical translation<br />

e) individual possession shared ownership<br />

Unlike a print text, which is always physically present in its entirety, the electronic text<br />

resides in the computer memory in a format not accessible <strong>to</strong> us, and is only temporarily<br />

realised on the screen. It is not transparent, i.e. not immediately understandable, we are<br />

dependent on the computer <strong>to</strong> translate it in<strong>to</strong> a form accessible <strong>to</strong> us. This is<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>matic of the increasingly technological environment and our dependency on<br />

mediating machines in the late zoth century society, which has been described by<br />

Douglas Cooper in his introduction <strong>to</strong> the programming language Pascal as follows:<br />

Once upon a time, it was possible <strong>to</strong> figure out what something did by inspecting it.<br />

That's because the final product usually relied on the everyday properties of the<br />

wood, metal, fabric it was build of. A catapult, a 100m, a printing press - it didn't<br />

matter, because there was a visible connection between the parts ofthe machine and<br />

what the machine did. It was, as Kenner puts it, the age of 'transparent technology,<br />

when machines were visual guides <strong>to</strong> their own workiniI6<br />

The computer "dematerialises" written trace (as opposed <strong>to</strong> pen, typewriter, print), but<br />

also "depersonalises" it. The author's self, that is constructed in a written text in physical<br />

stability and imagined au<strong>to</strong>nomy, becomes destabilised and dispersed in the electronic<br />

text. Similarly, at the receiving end, the construct ofthe reader becomes less graspable in<br />

a text with unstable boundaries and impermanent status." An electronic text can be<br />

duplicated at nearly no cost an infinite number of times - overturning notions of rarity,<br />

individual possession as well as originality. Mark Poster argues:<br />

Compare a novel written on a computer and s<strong>to</strong>red on a floppy disk with one<br />

composed in a manuscript or even a typescript. Manuscripts have value as originals.<br />

16 Douglas Cooper, Oh!Pascali, 3rd edition (New York and London, W.W.Nor<strong>to</strong>n, 1993>, p. XXI<br />

(referring <strong>to</strong> Hugh Kenner's The Mechanical Muse (Oxford, OUF, 1987».<br />

17 see: Mark Poster, The Mode of Information (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p.o, and<br />

Lanham. The Ekctronic Word, p.lI.<br />

Chapter I - page 6<br />

I