Colloquium on English - Research Institute for Waldorf Education

Colloquium on English - Research Institute for Waldorf Education

Colloquium on English - Research Institute for Waldorf Education

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

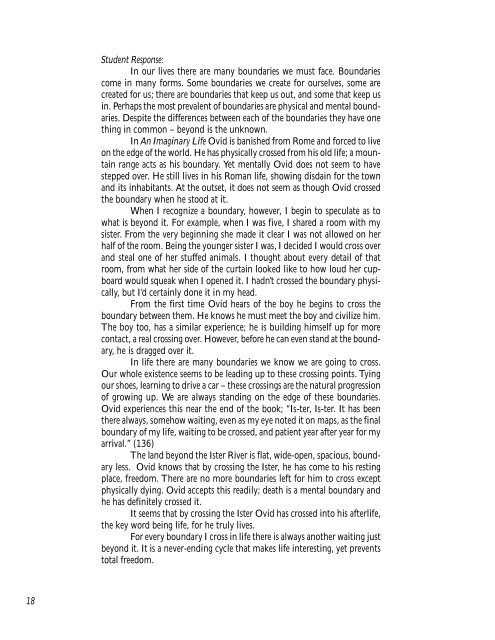

18<br />

Student Resp<strong>on</strong>se:<br />

In our lives there are many boundaries we must face. Boundaries<br />

come in many <strong>for</strong>ms. Some boundaries we create <strong>for</strong> ourselves, some are<br />

created <strong>for</strong> us; there are boundaries that keep us out, and some that keep us<br />

in. Perhaps the most prevalent of boundaries are physical and mental boundaries.<br />

Despite the differences between each of the boundaries they have <strong>on</strong>e<br />

thing in comm<strong>on</strong> – bey<strong>on</strong>d is the unknown.<br />

In An Imaginary Life Ovid is banished from Rome and <strong>for</strong>ced to live<br />

<strong>on</strong> the edge of the world. He has physically crossed from his old life; a mountain<br />

range acts as his boundary. Yet mentally Ovid does not seem to have<br />

stepped over. He still lives in his Roman life, showing disdain <strong>for</strong> the town<br />

and its inhabitants. At the outset, it does not seem as though Ovid crossed<br />

the boundary when he stood at it.<br />

When I recognize a boundary, however, I begin to speculate as to<br />

what is bey<strong>on</strong>d it. For example, when I was five, I shared a room with my<br />

sister. From the very beginning she made it clear I was not allowed <strong>on</strong> her<br />

half of the room. Being the younger sister I was, I decided I would cross over<br />

and steal <strong>on</strong>e of her stuffed animals. I thought about every detail of that<br />

room, from what her side of the curtain looked like to how loud her cupboard<br />

would squeak when I opened it. I hadn’t crossed the boundary physically,<br />

but I’d certainly d<strong>on</strong>e it in my head.<br />

From the first time Ovid hears of the boy he begins to cross the<br />

boundary between them. He knows he must meet the boy and civilize him.<br />

The boy too, has a similar experience; he is building himself up <strong>for</strong> more<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tact, a real crossing over. However, be<strong>for</strong>e he can even stand at the boundary,<br />

he is dragged over it.<br />

In life there are many boundaries we know we are going to cross.<br />

Our whole existence seems to be leading up to these crossing points. Tying<br />

our shoes, learning to drive a car – these crossings are the natural progressi<strong>on</strong><br />

of growing up. We are always standing <strong>on</strong> the edge of these boundaries.<br />

Ovid experiences this near the end of the book; “Is-ter, Is-ter. It has been<br />

there always, somehow waiting, even as my eye noted it <strong>on</strong> maps, as the final<br />

boundary of my life, waiting to be crossed, and patient year after year <strong>for</strong> my<br />

arrival.” (136)<br />

The land bey<strong>on</strong>d the Ister River is flat, wide-open, spacious, boundary<br />

less. Ovid knows that by crossing the Ister, he has come to his resting<br />

place, freedom. There are no more boundaries left <strong>for</strong> him to cross except<br />

physically dying. Ovid accepts this readily; death is a mental boundary and<br />

he has definitely crossed it.<br />

It seems that by crossing the Ister Ovid has crossed into his afterlife,<br />

the key word being life, <strong>for</strong> he truly lives.<br />

For every boundary I cross in life there is always another waiting just<br />

bey<strong>on</strong>d it. It is a never-ending cycle that makes life interesting, yet prevents<br />

total freedom.