Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

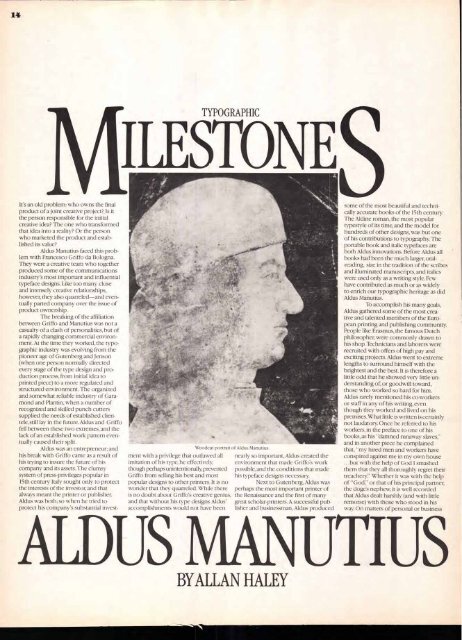

14<br />

It's an old problem: who owns the final<br />

product of a joint creative project?_Is it<br />

the person responsible for the initial<br />

creative idea? The one who transformed<br />

that idea into a reality? Or the person<br />

who marketed the product and established<br />

its value?<br />

Aldus Manutius faced this problem<br />

with Francesco Griffo da Bologna.<br />

They were a creative team who together<br />

produced some of the communications<br />

industry's most important and influential<br />

typeface designs. Like too many close<br />

and intensely creative relationships,<br />

however, they also quarreled—and eventually<br />

parted company over the issue of<br />

product ownership.<br />

The breaking of the affiliation<br />

between Griffo and Manutius was not a<br />

casualty of a clash of personalities, but of<br />

a rapidly changing commercial environment.<br />

At the time they worked, the typographic<br />

industry was evolving from the<br />

pioneer age of Gutenberg and Jenson<br />

(when one person normally directed<br />

every stage of the type design and production<br />

process, from initial idea to<br />

printed piece) to a more regulated and<br />

structured environment. The organized<br />

and somewhat reliable industry of Garamond<br />

and Plantin, when a number of<br />

recognized and skilled punch cutters<br />

supplied the needs of established clientele,<br />

still lay in the future. Aldus and Griffo<br />

fell between these two extremes, and the<br />

lack of an established work pattern eventually<br />

caused their split.<br />

Aldus was an entrepreneur; and<br />

his break with Griffo came as a result of<br />

his trying to insure the future of his<br />

company and its assets. The clumsy<br />

system of press-privileges popular in<br />

15th century Italy sought only to protect<br />

the interests of the investor, and that<br />

always meant the printer or publisher.<br />

Aldus was both; so when he tried to<br />

protect his company's substantial invest-<br />

ILESTONE<br />

TYPOGRAPHIC<br />

ment with a privilege that outlawed all<br />

imitation of his type, he effectively,<br />

though perhaps unintentionally, prevented<br />

Griffo from selling his best and most<br />

popular designs to other printers. It is no<br />

wonder that they quarreled. While there<br />

is no doubt about Griffo's creative genius,<br />

and that without his type designs Aldus'<br />

accomplishments would not have been<br />

nearly so important, Aldus created the<br />

environment that made Griffo's work<br />

possible, and the conditions that made<br />

his typeface designs necessary.<br />

Next to Gutenberg, Aldus was<br />

perhaps the most important printer of<br />

the Renaissance and the first of many<br />

great scholar-printers. A successful publisher<br />

and businessman, Aldus produced<br />

some of the most beautiful and technically<br />

accurate books of the 15th century.<br />

The Aldine roman, the most popular<br />

typestyle of its time, and the model for<br />

hundreds of other designs, was but one<br />

of his contributions to typography. The<br />

portable book and italic typefaces are<br />

both Aldus innovations. Before Aldus all<br />

books had been the much larger, oral-<br />

reading, size in the tradition of the scribes<br />

and illuminated manuscripts, and italics<br />

were used only as a writing style. Few<br />

have contributed as much or as widely<br />

to enrich our typographic heritage as did<br />

Aldus Manutius.<br />

To accomplish his many goals,<br />

Aldus gathered some of the most creative<br />

and talented members of the European<br />

printing and publishing community.<br />

People like Erasmus, the famous Dutch<br />

philosopher, were commonly drawn to<br />

his shop. Technicians and laborers were<br />

recruited with offers of high pay and<br />

exciting projects. Aldus went to extreme<br />

lengths to surround himself with the<br />

brightest and the best. It is therefore a<br />

little odd that he showed very little understanding<br />

of, or goodwill toward,<br />

those who worked so hard for him.<br />

Aldus rarely mentioned his co-workers<br />

or staff in any of his writing, even<br />

though they worked and lived on his<br />

premises. What little is written is certainly<br />

not laudatory. Once he referred to his<br />

workers, in the preface to one of his<br />

books, as his "damned runaway slaves,"<br />

and in another piece he complained<br />

that, "my hired men and workers have<br />

conspired against me in my own house<br />

...but with the help of God I smashed<br />

them that they all thoroughly regret their<br />

treachery" Whether it was with the help<br />

of "God," or that of his principal partner,<br />

the doge's nephew, it is well recorded<br />

that Aldus dealt harshly (and with little<br />

remorse) with those who stood in his<br />

way. On matters of personal or business<br />

ALDUS mANunus<br />

BYALLAN HALEY