Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Volume 12–4 (Low Res).pdf - U&lc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

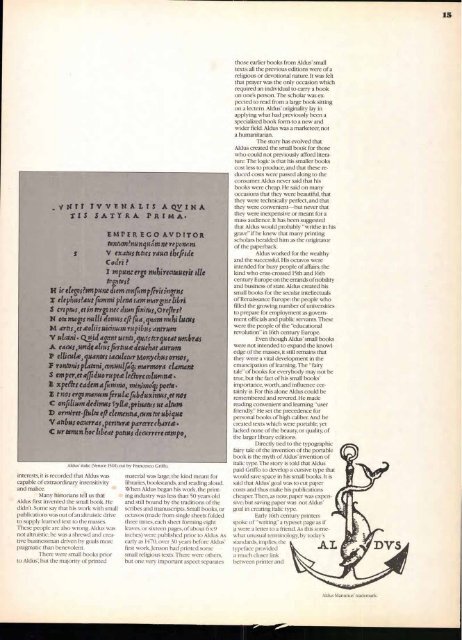

.,yN'TT TVVENALTS ACty:INA<br />

T1S SA.TYRA PRImA<br />

EMPER EGO AVDTTOR<br />

tanturn?nunqutm ne re ponem<br />

v exatus tocs rdua thefigde<br />

c °chi ?<br />

m punt ergo nuhirentautrit the<br />

trpses?<br />

It is elegas?pmpune diem confirm pflrisingens<br />

elephus?aut rummi plena ram margine Itbri<br />

S crsplus,etintrrgonecdamrt finitus,orefirs?<br />

N otamagrsWillidonutsef1 fut,cram nuhi lung<br />

M anis ,et Lou ir uicisu‘mrupibus antrum:<br />

V :da ta quid apt ucntz,gwas torqueat 107:brdS<br />

A tants , undtaltus fifrbuee dcuehat durum<br />

P cl/i cub e,quantits Sandefur Monychus ornos „<br />

rontanis platani,amustlfaig; marmora clamant<br />

S emper,et afficluo ru ?tee teflon coluInnit<br />

E xpeeIrs calms 4frim mirsima'q; poets.<br />

E t nos ergo manum firulecfiduluximus,et nos<br />

C onfilium cleclimus Sylice,piiikttus ut altum<br />

ormiret flubs: eft clemenna,cum tot ubique<br />

V a tsbus ocrurras ,pertturx parcerc chartie<br />

C ur tanun hoc ltheat potuss clecurrere atm po,<br />

Aldus' italic (Venice 1501) cut by Francesco Griffo.<br />

interests, it is recorded that Aldus was<br />

capable of extraordinary insensitivity<br />

and malice.<br />

Many historians tell us that<br />

Aldus first invented the small book. He<br />

didn't. Some say that his work with small<br />

publications was out of an altruistic drive<br />

to supply learned text to the masses.<br />

These people are also wrong. Aldus was<br />

not altruistic; he was a shrewd and creative<br />

businessman driven by goals more<br />

pragmatic than benevolent.<br />

There were small books prior<br />

to Aldus', but the majority of printed<br />

material was large; the kind meant for<br />

libraries, bookstands, and reading aloud.<br />

When Aldus began his work, the printing-industry<br />

was less than 50 years old<br />

and still bound by the traditions of the<br />

scribes and manuscripts. Small books, or<br />

octavos (made from single sheets folded<br />

three times, each sheet forming eight<br />

leaves, or sixteen pages, of about 6x9<br />

inches) were published prior to Aldus. As<br />

early as 1470, over 30 years before Aldus'<br />

first work, Jenson had printed some<br />

small religious texts. There were others,<br />

but one very important aspect separates<br />

those earlier books from Aldus' small<br />

texts: all the previous editions were of a<br />

religious or devotional nature. It was felt<br />

that prayer was the only occasion which<br />

required an individual to carry a book<br />

on one's person. The scholar was expected<br />

to read from a large book sitting<br />

on a lectern. Aldus' originality lay in<br />

applying what had previously been a<br />

specialized book form-to a new and<br />

wider field. Aldus was a marketeer, not<br />

a humanitarian.<br />

The story has evolved that<br />

Aldus created the small book for those<br />

who could not previously afford literature.<br />

The logic is that his smaller books<br />

cost less to produce, and that these reduced<br />

costs were passed along to the<br />

consumer. Aldus never said that his<br />

books were cheap. He said on many<br />

occasions that they were beautiful, that<br />

they were technically perfect, and that<br />

they were convenient—but never that<br />

they were inexpensive or meant for a<br />

mass audience. It has been suggested<br />

that Aldus would probably "writhe in his<br />

grave" if he knew that many printing<br />

scholars heralded him as the originator<br />

of the paperback.<br />

Aldus worked for the wealthy<br />

and the successful. His octavos were<br />

intended for busy people of affairs; the<br />

kind who criss-crossed 15th and 16th<br />

century Europe on the errands of nobility<br />

and business of state. Aldus created his<br />

small books for the secular intellectuals<br />

of Renaissance Europe: the people who<br />

filled the growing number of universities<br />

to prepare for employment as government<br />

officials and public servants. These<br />

were the people of the "educational<br />

revolution" in 16th century Europe.<br />

Even though Aldus' small books<br />

were not intended to expand the knowledge<br />

of the masses, it still remains that<br />

they were a vital development in the<br />

emancipation of learning. The "fairy<br />

tale" of books for everybody may not be<br />

true, but the fact of his small books'<br />

importance, worth, and influence certainly<br />

is. For this alone Aldus could be<br />

remembered and revered. He made<br />

reading convenient and learning "user<br />

friendly." He set the precedence for<br />

personal books of high caliber. And he<br />

created texts which were portable, yet<br />

lacked none of the beauty, or quality, of<br />

the larger library editions.<br />

Directly tied to the typographic<br />

fairy tale of the invention of the portable<br />

book is the myth of Aldus' invention'of<br />

italic type. The story is told that Aldus<br />

paid Griffo to develop a cursive type that<br />

would save space in his small books. It is<br />

said that Aldus' goal was to cut paper<br />

costs and thus make his publications<br />

cheaper. Then, as now, paper was expensive;<br />

but saving paper was not Aldus'<br />

goal in creating italic type.<br />

Early 16th century printers<br />

spoke of "writing" a typeset page as if<br />

it were a letter to a friend. As this somewhat<br />

unusual terminology, by today's<br />

standards, implies, the<br />

typeface provided<br />

a much closer link<br />

between printer and<br />

15