Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

5. Conclusions<br />

In all South-East Asian countries except Brunei Darussalam, Lao PDR and Singapore, local languages<br />

are used in education at least to some extent. Brunei and Singapore use several languages as the<br />

media of instruction in the government education system, whereas Lao PDR uses only the national<br />

language. However, it can be assumed that local languages are used orally also in these countries.<br />

In Myanmar, only the non-governmental sector provides local language education, and only in<br />

non-formal education. The use of local languages in Cambodia and Thailand is still at the beginning<br />

stages in some pilot projects. In Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Viet Nam, local languages<br />

are being used in various ways, but only in a few cases as the medium of instruction.<br />

Research and practical experiences from around the world demonstrate that the use of local languages<br />

in education is feasible. Curriculum development and materials production in local languages can<br />

be cost-effective. Innovative teaching and learning practises, and the use of native speakers of<br />

local languages as teachers, can help alleviate challenges that may seem to hinder the provision of<br />

education in the mother tongue. Local language education can be provided in ways that are not<br />

necessarily much more expensive than other basic education, particularly if education provided also<br />

reduces minority student retention and attrition rates (CAL 2001; Dutcher & Tucker 1996; Klaus<br />

2003a, 2003b; Litteral 1999; Obanya 1999; Patrinos & Velez 1996; Tucker 1998). This is an extremely<br />

important point, as a common argument against bilingual and multilingual education is its assumed<br />

costliness.<br />

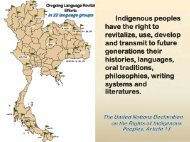

Furthermore, there is sufficient evidence to prove that all languages can be written, and consequently<br />

used, in education. Numerous cases from South-East Asia and around the world demonstrate that<br />

collaboration of local communities and linguists can produce viable writing systems for previously<br />

unwritten languages, or further develop languages that already have tentative writing systems. The<br />

use of newly written languages in education, however, usually requires also the contribution of<br />

education specialists. The initial language development of a previously unwritten language can be<br />

expensive, but cooperation between local communities, academics, NGOs, civil society organizations,<br />

various donor agencies, as well as national governments, enable this to happen even in small language<br />

communities. Language development can be economically viable through cooperation (e.g. Klaus<br />

2003a, 2003b; Litteral 1999; Robinson 1999; UNESCO 2003b). The principle of collaboration<br />

applies to all parts of local language education.<br />

Most members of ethnolinguistic minority communities in South-East Asia have to start their education<br />

in a language they neither understand nor speak. Lessons learned elsewhere in the use of local<br />

languages could certainly be adapted to these contexts. Biliteracy and mother tongue-based bilingual<br />

education benefit particularly those who are monolingual in a local language or who have an<br />

insufficient knowledge of the currently used medium of instruction. Consequently, it is imperative<br />

to search for different options that could be considered viable for alleviating the constraints of<br />

ethnolinguistic minority education in South-East Asia. This would benefit hundreds of minority<br />

communities and tens of millions of people.<br />

118