Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

Part II.pdf - MTB-MLE Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

There is a lot of variation in the use of local languages in education, depending on the geographical<br />

area and ethnolinguistic group. There are strong and weak forms of bilingual education, and various<br />

shades in between. In the strong forms, an ethnic language, usually a regional LWC with a long<br />

literate history, is used as the medium of instruction from primary school through high school. In<br />

such programmes, Mandarin is taught as a second language starting from Grade 2 or 3. The balance<br />

between the use of the local and national language differs. Minorities benefiting from strong forms<br />

of bilingual education include Kazakhs, Koreans, Mongolians, Uygurs and Tibetans (Blachford 1997;<br />

Huang 2003; Leclerc 2004d; Stites 1999; Zhou 1992).<br />

The weak forms of bilingual education offer local language instruction in pre-primary education<br />

for a fairly short period of time (6-12 months). After this, the minority children are mainstreamed<br />

with Chinese speaking students. Blachford (1997, 161) calls this type “in name only” bilingual<br />

education. Other examples of the weak forms are cases in which ethnic languages are taught as<br />

a subject at different levels of the educational system (Blachford 1997; Stites 1999; Xiao 1998;<br />

Zhou 1992). The most common local language use in Chinese bilingual education is found in<br />

transitional programmes. Such programmes start with the students’ mother tongue, but as soon as<br />

the students understand Mandarin to some extent, it becomes the main medium of instruction.<br />

The transitional programmes aim to help children learn the national language, but maintenance of<br />

the mother tongue is not seen as important (Blachford 1997; Stites 1999; Xiao 1998; Zhou 1992).<br />

Chinese experience shows, however, that learning achievements of students in bilingual programmes<br />

– even some transitional ones – are better than in Chinese-only education for ethnic minorities<br />

(Blachford 1997, 161; Huang 2003; Xiao 1998, 230).<br />

Common difficulties faced in the use of local languages in China include: a lack of writing systems;<br />

a lack of qualified minority language teachers; a lack of texts and materials in minority languages;<br />

translation of textbooks from Chinese into minority languages without any adaptation; rapid transition<br />

from local languages to Mandarin; and negative attitudes towards the importance and usefulness<br />

of minority language education (Blachford 1997, 161; Cobbey 2003; Huang 2003; Lin 1997; Stites<br />

1999, 95; Zhou 1992, 43). Reasons for good progress in bilingual education endeavours in China<br />

include: positive and progressive approaches to bilingual education by local authorities, strong<br />

support of academics, and the major role of minority communities in curriculum development and<br />

materials production.<br />

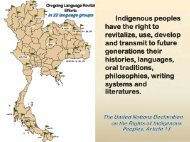

Many minority languages of Southwest China or related varieties are spoken in South-East Asia,<br />

as well. In this region, there are documented examples of well-established programmes of bilingual<br />

education and mother-tongue literacy. Some of them are allegedly strong forms of bilingual education,<br />

as with Bai, Dai, Jingpo, Naxi, Zhuang and Yi languages (APPEAL 2001; Huang 2003; Jernudd<br />

1999; Liu 2000). In practice, however, few such efforts continue today, and in many “bilingual<br />

programmes,” the local language component is weak (Blachford 1997, 162-163). For example,<br />

the bilingual education for the Bai cited in the literature has not been continued, except in a very<br />

limited way to help older elementary school students improve their essay writing (L. Billard, pers.<br />

comm. 2004). However, plans to implement a new bilingual project amongst the Bai are underway.<br />

Very promising are recent experiences among the Dong (or Kam) of Guizhou Province. A<br />

nine-year pilot programme of bilingual education launched in 2000 uses Dong and Mandarin, starting<br />

with two years of preschool in which only Dong is used. Mandarin is introduced in primary school,<br />

108