The Ecology of Hydric Hammocks - USGS National Wetlands ...

The Ecology of Hydric Hammocks - USGS National Wetlands ...

The Ecology of Hydric Hammocks - USGS National Wetlands ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

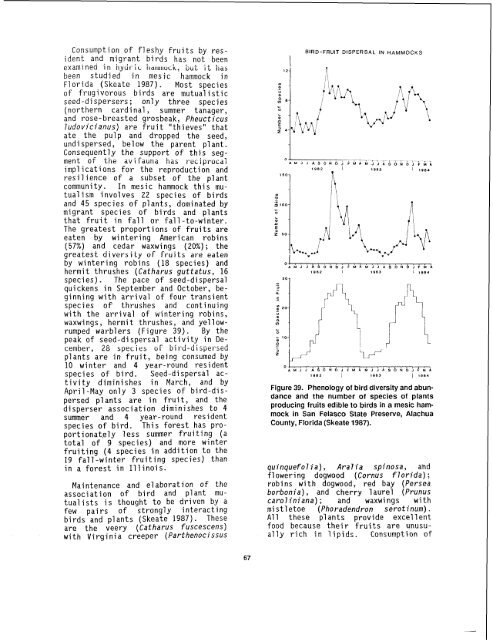

Consumption <strong>of</strong> fleshy fruits by residentand migrant birds has not beenexamined irl ityCir i~ iia~tltlt~~k, but it hasbeen studied in mesic hammock inFlorida (Skeate 1987). Most species<strong>of</strong> frugivorous birds are mutual isticseed-di spersers ; only three species(northern cardinal, summer tanager,and rose-breasted grosbeak, Pheucticus7udovicianus) are fruit "thieves" thatate the pulp and dropped the seed,undi spersed, be1 ow the parent plant.Consequently the support <strong>of</strong> this segment<strong>of</strong> the dvifauna has re~ipro~dlimp1 icati ons for the reproduction andresilience <strong>of</strong> a subset <strong>of</strong> the plantcommunity. In mesic hammock this mutualism involves 22 species <strong>of</strong> birdsand 45 species <strong>of</strong> plants, dominated bymigrant species <strong>of</strong> birds and plantsthat fruit in fall or fall -to-winter.<strong>The</strong> greatest proportions <strong>of</strong> fruits areeaten by wintering American robins(57%) and cedar waxwings (20%); thegreatest diversity <strong>of</strong> fruits are eatenby wintering robins (18 species) andhermit thrushes (Catharus guttatus, 16species). <strong>The</strong> pace <strong>of</strong> seed-dispersalquickens in September and October, beginningwith arrival <strong>of</strong> four transientspecies <strong>of</strong> thrushes and continuingwith the arrival <strong>of</strong> wintering robins,waxwings, hermit thrushes, and ye1 1 owrumpedwarblers (Figure 39). By thepeak <strong>of</strong> seed-dispersal activity in December,28 species <strong>of</strong> bi rd-di spersedplants are in fruit, being consumed by10 winter and 4 year-round residentspecies <strong>of</strong> bird. Seed-di spersal activitydiminishes in March, and byApril -May only 3 species <strong>of</strong> bird-dispersedplants are in fruit, and thedisperser association diminishes to 4summer and 4 year-round residentspecies <strong>of</strong> bird. This forest has proportionatglyless summer fruiting (atotal <strong>of</strong> 9 species) and more winterfruiting (4 species in addition to the19 fall-winter fruiting species) thanin a forest in Illinois.Maintenance and elaboration <strong>of</strong> theassociation <strong>of</strong> bird and plant mutualist~is thought to be driven by afew pairs <strong>of</strong> strongly interactingbirds and plants (Skeate 1987). <strong>The</strong>seare the veery (Catharus fuscescens)with Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus1BIRD-FRUIT DISPERSAL IN HAMMOCKSFigure 39. Phenology <strong>of</strong> bird diversity and abundanceand the number <strong>of</strong> species <strong>of</strong> plantsproducing fruits edible to birds in a mesic hammockin San Felasco State Preserve, AlachuaCounty, Florida (Skeate 1987).quinquefo7 ia) , Aral ia spinosa, andflowering dogwood (Cornus f 1 orida) ;robins with dogwood, red bay (Perseaborbonia), and cherry laurel (Prunuscaro7iniana) ; and waxwings withmistletoe (Phoradendron serotinum) .All these plants provide excellentfood because their fruits are unusuallyrich in lipids. Consumption <strong>of</strong>