- Page 2:

Peter Schneider Extragalactic Astro

- Page 8:

Prof. Dr. Peter Schneider Argelande

- Page 12:

Preface VI ter aspects are discusse

- Page 16:

List of Contents VIII 2.5.1 The Gra

- Page 20:

List of Contents X 5. Active Galact

- Page 24:

List of Contents XII 8. Cosmology I

- Page 28:

List of Contents XIV D. Recommended

- Page 32:

1. Introduction and Overview 2 Fig.

- Page 36:

1. Introduction and Overview 4 othe

- Page 40:

1. Introduction and Overview 6 obje

- Page 44:

1. Introduction and Overview 8 Fig.

- Page 48:

1. Introduction and Overview 10 Fig

- Page 52:

1. Introduction and Overview 12 Fig

- Page 56:

1. Introduction and Overview 14 Fig

- Page 60:

1. Introduction and Overview 16 of

- Page 64:

1. Introduction and Overview 18 app

- Page 68:

1. Introduction and Overview 20 Fig

- Page 72:

1. Introduction and Overview 22 Fig

- Page 76:

1. Introduction and Overview 24 Fig

- Page 80:

1. Introduction and Overview 26 spe

- Page 84:

1. Introduction and Overview 28 Fig

- Page 88:

1. Introduction and Overview 30 Fig

- Page 92:

1. Introduction and Overview 32 Fig

- Page 98:

2. The Milky Way as a Galaxy 35 The

- Page 102:

2.2 Determination of Distances With

- Page 106:

2.2 Determination of Distances With

- Page 110:

2.2 Determination of Distances With

- Page 114:

2.2 Determination of Distances With

- Page 118:

2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy Fig

- Page 122:

2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy a c

- Page 126:

2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy Fig

- Page 130: 2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy B-s

- Page 134: 2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy Fro

- Page 138: 2.3 The Structure of the Galaxy tha

- Page 142: 2.4 Kinematics of the Galaxy 57 2.4

- Page 146: 2.4 Kinematics of the Galaxy which

- Page 150: 2.4 Kinematics of the Galaxy where

- Page 154: 2.4 Kinematics of the Galaxy center

- Page 158: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

- Page 162: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

- Page 166: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

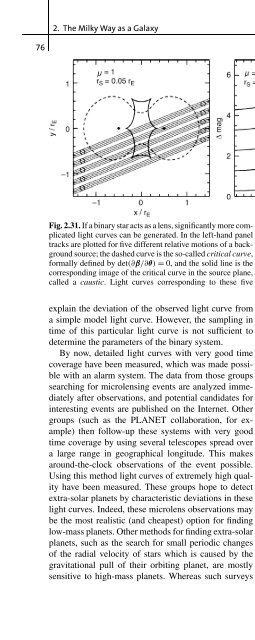

- Page 170: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

- Page 174: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

- Page 178: 2.5 The Galactic Microlensing Effec

- Page 184: 2. The Milky Way as a Galaxy 78 bee

- Page 188: 2. The Milky Way as a Galaxy 80 Fig

- Page 192: 2. The Milky Way as a Galaxy 82 Fig

- Page 196: 2. The Milky Way as a Galaxy 84 any

- Page 202: 3. The World of Galaxies 87 The ins

- Page 206: 3.1 Classification these names are

- Page 210: 3.2 Elliptical Galaxies 91 Fig. 3.5

- Page 214: 3.2 Elliptical Galaxies 93 Fig. 3.7

- Page 218: 3.2 Elliptical Galaxies anisotropic

- Page 222: 3.2 Elliptical Galaxies Fig. 3.12.

- Page 226: 3.3 Spiral Galaxies 99 Fig. 3.14. T

- Page 230:

3.3 Spiral Galaxies 101 Fig. 3.15.

- Page 234:

3.3 Spiral Galaxies luminous galaxi

- Page 238:

3.4 Scaling Relations 105 Fig. 3.20

- Page 242:

3.4 Scaling Relations gas, which ca

- Page 246:

3.5 Black Holes in the Centers of G

- Page 250:

3.5 Black Holes in the Centers of G

- Page 254:

3.6 Extragalactic Distance Determin

- Page 258:

3.6 Extragalactic Distance Determin

- Page 262:

3.7 Luminosity Function of Galaxies

- Page 266:

3.7 Luminosity Function of Galaxies

- Page 270:

3.8 Galaxies as Gravitational Lense

- Page 274:

3.8 Galaxies as Gravitational Lense

- Page 278:

3.8 Galaxies as Gravitational Lense

- Page 282:

3.8 Galaxies as Gravitational Lense

- Page 286:

3.8 Galaxies as Gravitational Lense

- Page 290:

3.9 Population Synthesis 131 Fig. 3

- Page 294:

3.9 Population Synthesis The integr

- Page 298:

3.9 Population Synthesis photometri

- Page 302:

3.9 Population Synthesis 137 Fig. 3

- Page 306:

3.10 Chemical Evolution of Galaxies

- Page 310:

4. Cosmology I: Homogeneous Isotrop

- Page 314:

4.1 Introduction and Fundamental Ob

- Page 318:

4.2 An Expanding Universe the Hubbl

- Page 322:

4.2 An Expanding Universe in which

- Page 326:

4.2 An Expanding Universe physical

- Page 330:

4.2 An Expanding Universe time. Hen

- Page 334:

4.3 Consequences of the Friedmann E

- Page 338:

4.3 Consequences of the Friedmann E

- Page 342:

4.3 Consequences of the Friedmann E

- Page 346:

4.3 Consequences of the Friedmann E

- Page 350:

4.4 Thermal History of the Universe

- Page 354:

4.4 Thermal History of the Universe

- Page 358:

4.4 Thermal History of the Universe

- Page 362:

4.4 Thermal History of the Universe

- Page 366:

4.5 Achievements and Problems of th

- Page 370:

4.5 Achievements and Problems of th

- Page 374:

4.5 Achievements and Problems of th

- Page 378:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 175 The l

- Page 382:

5.1 Introduction 5.1 Introduction 5

- Page 386:

5.1 Introduction 179 Fig. 5.5. Radi

- Page 390:

5.1 Introduction The synchrotron sp

- Page 394:

5.2 AGN Zoology have in common stro

- Page 398:

5.3 The Central Engine: A Black Hol

- Page 402:

5.3 The Central Engine: A Black Hol

- Page 406:

5.3 The Central Engine: A Black Hol

- Page 410:

5.3 The Central Engine: A Black Hol

- Page 414:

5.3 The Central Engine: A Black Hol

- Page 418:

5.4 Components of an AGN 5.4 Compon

- Page 422:

5.4 Components of an AGN transition

- Page 426:

5.4 Components of an AGN Fig. 5.22.

- Page 430:

5.4 Components of an AGN by magneti

- Page 434:

5.4 Components of an AGN sible to o

- Page 438:

5.4 Components of an AGN ity of an

- Page 444:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 208 radia

- Page 448:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 210 Fig.

- Page 452:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 212 5.5.4

- Page 456:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 214 elect

- Page 460:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 216 QSOs

- Page 464:

5. Active Galactic Nuclei 218 tion.

- Page 470:

5.6 AGNs and Cosmology 221 ize hydr

- Page 474:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 478:

6.1 The Local Group 225 Table 6.1.

- Page 484:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 488:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 492:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 496:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 500:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 504:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 508:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 512:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 516:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 520:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 524:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 528:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 532:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 536:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 540:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 544:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 548:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 552:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 556:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 560:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 564:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 568:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 572:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 576:

6. Clusters and Groups of Galaxies

- Page 582:

7. Cosmology II: Inhomogeneities in

- Page 586:

7.2 Gravitational Instability gravi

- Page 590:

7.2 Gravitational Instability i.e.,

- Page 594:

7.3 Description of Density Fluctuat

- Page 598:

7.4 Evolution of Density Fluctuatio

- Page 602:

7.4 Evolution of Density Fluctuatio

- Page 606:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 610:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 614:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 618:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 622:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 626:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 630:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 634:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 638:

7.5 Non-Linear Structure Evolution

- Page 642:

7.7 Origin of the Density Fluctuati

- Page 648:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 652:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 656:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 660:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 664:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 668:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 672:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 676:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 680:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 684:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 688:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 692:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 696:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 700:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 704:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 708:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 712:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 716:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 720:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 724:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 728:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 732:

352 8. Cosmology III: The Cosmologi

- Page 736:

8. Cosmology III: The Cosmological

- Page 740:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 35

- Page 744:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 35

- Page 748:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 36

- Page 752:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 36

- Page 756:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 36

- Page 760:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 36

- Page 764:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 36

- Page 768:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 37

- Page 772:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 37

- Page 776:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 37

- Page 780:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 37

- Page 784:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 37

- Page 788:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 38

- Page 792:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 38

- Page 796:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 38

- Page 800:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 38

- Page 804:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 38

- Page 808:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 39

- Page 812:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 39

- Page 816:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 39

- Page 820:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 39

- Page 824:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 39

- Page 828:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 40

- Page 832:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 40

- Page 836:

9. The Universe at High Redshift 40

- Page 842:

10. Outlook 407 In the final chapte

- Page 846:

10. Outlook telescope will start a

- Page 850:

10. Outlook New windows to the Univ

- Page 854:

10. Outlook understand why the dens

- Page 858:

Appendix

- Page 864:

A. The Electromagnetic Radiation Fi

- Page 868:

A. The Electromagnetic Radiation Fi

- Page 872:

A. The Electromagnetic Radiation Fi

- Page 878:

B. Properties of Stars 425 In this

- Page 882:

B.3 Structure and Evolution of Star

- Page 886:

B.3 Structure and Evolution of Star

- Page 894:

D. Recommended Literature 433 In th

- Page 898:

D.3 Review Articles, Current Litera

- Page 904:

E. Acronyms Used 438 GRB Gamma-Ray

- Page 910:

F. Figure Credits 441 Chapter 1 1.1

- Page 914:

F. Figure Credits 1.25 Source: R. W

- Page 918:

F. Figure Credits Nik Szymanek. bot

- Page 922:

F. Figure Credits 5.5 Credit: Laing

- Page 926:

F. Figure Credits 6.26 Source: http

- Page 930:

F. Figure Credits 8.24 Credit: Hu &

- Page 934:

Subject Index 453 A AB magnitudes 4

- Page 938:

Subject Index 455 Doppler effect 38

- Page 942:

Subject Index 457 -dampedLyα syste

- Page 946:

Subject Index 459 virial theorem 13