Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa

Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa

Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

66 <strong>Myth</strong>, protest <strong>and</strong> struggle <strong>in</strong> Ok<strong>in</strong>awa<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, covered the US l<strong>and</strong> acquisition<br />

with titles <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g words such as ‘bulldozers <strong>and</strong> bayonets’, ‘exploitation of<br />

Ok<strong>in</strong>awan labour’, <strong>and</strong> denial of Ok<strong>in</strong>awans’ basic human rights under the US<br />

military adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>in</strong> a series of articles from 13 January 1955. After Asahi<br />

Shimbun requested the government to take action to protect Ok<strong>in</strong>awa, many<br />

Ok<strong>in</strong>awans felt they ‘ga<strong>in</strong>ed a million supporters’, <strong>and</strong> ‘a beam of light entered <strong>in</strong><br />

the Dark Age’ (Arasaki 1976: 139–40).<br />

The Ie-jima farmers’ letters reveal general expectations many Ok<strong>in</strong>awans had<br />

of the Japanese government <strong>and</strong> the people: if Ok<strong>in</strong>awa returns to Japan, Ok<strong>in</strong>awans<br />

will be free from US military dom<strong>in</strong>ation. This expectation, however, was bitterly<br />

betrayed <strong>in</strong> the course of the development of the new US–Japan security alliance.<br />

Reflect<strong>in</strong>g this change <strong>in</strong> perspective towards ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> Japan <strong>in</strong> 1969, Arasaki<br />

describes the letter-writ<strong>in</strong>g strategy as a ‘weakness’ of the Ie-jima struggle (Arasaki<br />

1969: 90). A few years later, however, as he acknowledges (1976: 142), the farmers<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ok<strong>in</strong>awans <strong>in</strong> general felt isolated from the rest of the world under the US<br />

military authoritarian rule, <strong>and</strong> sympathy from the ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> population was the<br />

only hope.<br />

In January 1955, 15 Maja households were ordered to evacuate. Prior negotiations<br />

with the US military had significantly reduced the number of houses to be evacuated,<br />

from the <strong>in</strong>itial 152 households <strong>in</strong> Maja <strong>and</strong> Nishizaki. The military shifted half<br />

of the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g range from l<strong>and</strong> to water, which ‘was the result of our persistent<br />

negotiation <strong>and</strong> plead<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> retrospect’ (Ahagon 1973: 66). At around 8am on<br />

11 March 1955, three large l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g vessels suddenly appeared off the east coast<br />

of Ie-jima. 26 On 14 March, the bulldozers entered Maja, crush<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the sweet potatoes, peanuts, sugar cane <strong>and</strong> p<strong>in</strong>e trees that we had carefully<br />

grown. Our houses, furniture <strong>and</strong> water tanks, which were so crucial for<br />

survival were covered by soil. Soldiers took helpless people outside, <strong>and</strong> set<br />

some houses on fire. Namizato Seiji, the owner of one of the 13 destroyed<br />

houses, pleaded to stop <strong>in</strong> front of the bulldozers, but the soldiers beat him up,<br />

arrested him <strong>and</strong> sent him to the military prison. Soldiers took sick children<br />

outside <strong>and</strong> picked up the owners of the houses, grabbed their arms <strong>and</strong> forced<br />

them to receive some cash.<br />

(Ahagon 1973: 89–91)<br />

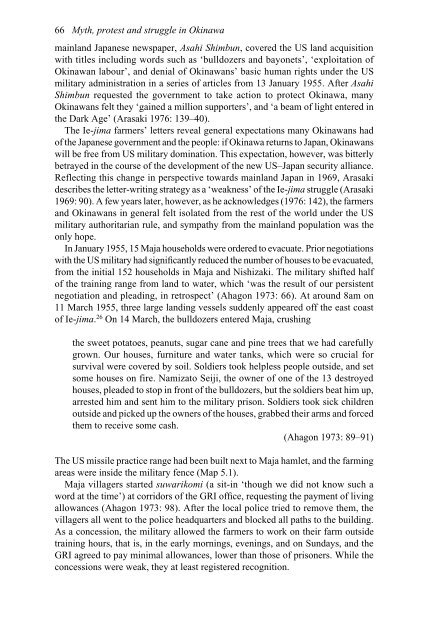

The US missile practice range had been built next to Maja hamlet, <strong>and</strong> the farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

areas were <strong>in</strong>side the military fence (Map 5.1).<br />

Maja villagers started suwarikomi (a sit-<strong>in</strong> ‘though we did not know such a<br />

word at the time’) at corridors of the GRI office, request<strong>in</strong>g the payment of liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

allowances (Ahagon 1973: 98). After the local police tried to remove them, the<br />

villagers all went to the police headquarters <strong>and</strong> blocked all paths to the build<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

As a concession, the military allowed the farmers to work on their farm outside<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g hours, that is, <strong>in</strong> the early morn<strong>in</strong>gs, even<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong> on Sundays, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

GRI agreed to pay m<strong>in</strong>imal allowances, lower than those of prisoners. While the<br />

concessions were weak, they at least registered recognition.