Torrance Journal for Applied Creativity

TorranceJournal_V1

TorranceJournal_V1

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Too High Expectations Lead to Underachievement<br />

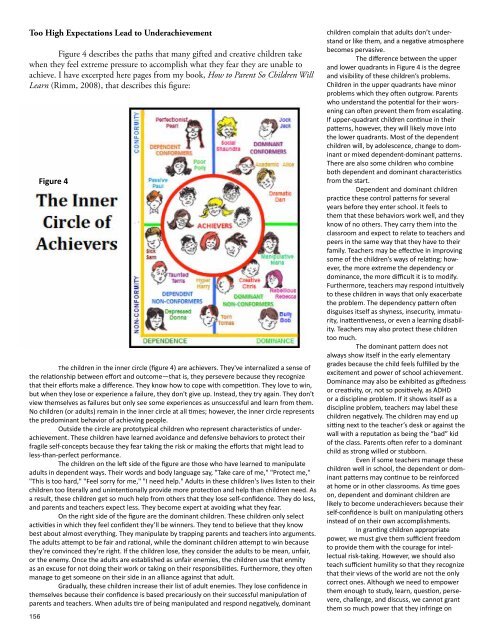

Figure 4 describes the paths that many gifted and creative children take<br />

when they feel extreme pressure to accomplish what they fear they are unable to<br />

achieve. I have excerpted here pages from my book, How to Parent So Children Will<br />

Learn (Rimm, 2008), that describes this figure:<br />

156<br />

Figure 4<br />

The children in the inner circle (figure 4) are achievers. They've internalized a sense of<br />

the relationship between ef<strong>for</strong>t and outcome—that is, they persevere because they recognize<br />

that their ef<strong>for</strong>ts make a difference. They know how to cope with competition. They love to win,<br />

but when they lose or experience a failure, they don't give up. Instead, they try again. They don't<br />

view themselves as failures but only see some experiences as unsuccessful and learn from them.<br />

No children (or adults) remain in the inner circle at all times; however, the inner circle represents<br />

the predominant behavior of achieving people.<br />

Outside the circle are prototypical children who represent characteristics of underachievement.<br />

These children have learned avoidance and defensive behaviors to protect their<br />

fragile self-concepts because they fear taking the risk or making the ef<strong>for</strong>ts that might lead to<br />

less-than-perfect per<strong>for</strong>mance.<br />

The children on the left side of the figure are those who have learned to manipulate<br />

adults in dependent ways. Their words and body language say, "Take care of me," "Protect me,"<br />

"This is too hard," "Feel sorry <strong>for</strong> me," "I need help." Adults in these children's lives listen to their<br />

children too literally and unintentionally provide more protection and help than children need. As<br />

a result, these children get so much help from others that they lose self-confidence. They do less,<br />

and parents and teachers expect less. They become expert at avoiding what they fear.<br />

On the right side of the figure are the dominant children. These children only select<br />

activities in which they feel confident they’ll be winners. They tend to believe that they know<br />

best about almost everything. They manipulate by trapping parents and teachers into arguments.<br />

The adults attempt to be fair and rational, while the dominant children attempt to win because<br />

they’re convinced they’re right. If the children lose, they consider the adults to be mean, unfair,<br />

or the enemy. Once the adults are established as unfair enemies, the children use that enmity<br />

as an excuse <strong>for</strong> not doing their work or taking on their responsibilities. Furthermore, they often<br />

manage to get someone on their side in an alliance against that adult.<br />

Gradually, these children increase their list of adult enemies. They lose confidence in<br />

themselves because their confidence is based precariously on their successful manipulation of<br />

parents and teachers. When adults tire of being manipulated and respond negatively, dominant<br />

children complain that adults don’t understand<br />

or like them, and a negative atmosphere<br />

becomes pervasive.<br />

The difference between the upper<br />

and lower quadrants in Figure 4 is the degree<br />

and visibility of these children’s problems.<br />

Children in the upper quadrants have minor<br />

problems which they often outgrow. Parents<br />

who understand the potential <strong>for</strong> their worsening<br />

can often prevent them from escalating.<br />

If upper-quadrant children continue in their<br />

patterns, however, they will likely move into<br />

the lower quadrants. Most of the dependent<br />

children will, by adolescence, change to dominant<br />

or mixed dependent-dominant patterns.<br />

There are also some children who combine<br />

both dependent and dominant characteristics<br />

from the start.<br />

Dependent and dominant children<br />

practice these control patterns <strong>for</strong> several<br />

years be<strong>for</strong>e they enter school. It feels to<br />

them that these behaviors work well, and they<br />

know of no others. They carry them into the<br />

classroom and expect to relate to teachers and<br />

peers in the same way that they have to their<br />

family. Teachers may be effective in improving<br />

some of the children’s ways of relating; however,<br />

the more extreme the dependency or<br />

dominance, the more difficult it is to modify.<br />

Furthermore, teachers may respond intuitively<br />

to these children in ways that only exacerbate<br />

the problem. The dependency pattern often<br />

disguises itself as shyness, insecurity, immaturity,<br />

inattentiveness, or even a learning disability.<br />

Teachers may also protect these children<br />

too much.<br />

The dominant pattern does not<br />

always show itself in the early elementary<br />

grades because the child feels fulfilled by the<br />

excitement and power of school achievement.<br />

Dominance may also be exhibited as giftedness<br />

or creativity, or, not so positively, as ADHD<br />

or a discipline problem. If it shows itself as a<br />

discipline problem, teachers may label these<br />

children negatively. The children may end up<br />

sitting next to the teacher’s desk or against the<br />

wall with a reputation as being the “bad” kid<br />

of the class. Parents often refer to a dominant<br />

child as strong willed or stubborn.<br />

Even if some teachers manage these<br />

children well in school, the dependent or dominant<br />

patterns may continue to be rein<strong>for</strong>ced<br />

at home or in other classrooms. As time goes<br />

on, dependent and dominant children are<br />

likely to become underachievers because their<br />

self-confidence is built on manipulating others<br />

instead of on their own accomplishments.<br />

In granting children appropriate<br />

power, we must give them sufficient freedom<br />

to provide them with the courage <strong>for</strong> intellectual<br />

risk-taking. However, we should also<br />

teach sufficient humility so that they recognize<br />

that their views of the world are not the only<br />

correct ones. Although we need to empower<br />

them enough to study, learn, question, persevere,<br />

challenge, and discuss, we cannot grant<br />

them so much power that they infringe on