You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

53<br />

This started with the Convention encouraging<br />

priests to leave the Clergy and get<br />

married. In certain cases, they were even<br />

forced to do so. Those who refused faced<br />

prosecution and even deportation. In a<br />

more extreme move, the Convention<br />

banned all public worship in October 1793<br />

and proceeded to remove all visible reminders<br />

of Christianity from view.<br />

Churches were even closed and turned<br />

into industrial buildings, whilst the Gregorian<br />

calendar was<br />

replaced with the<br />

new Revolutionary<br />

calendar, which removed<br />

Sunday as a<br />

day of worship and<br />

instead implemented<br />

a ten-day week. But<br />

this wasn’t the end of<br />

religion in France. Instead,<br />

the revolutionary<br />

government<br />

sought to replace Catholicism<br />

with a religion<br />

celebrating the<br />

Revolution itself,<br />

which would honour<br />

revolutionary ‘martyrs’<br />

and use the red<br />

liberty cap as one of<br />

its symbols. This<br />

movement gave birth<br />

to several ‘cults’, including<br />

the Cult of<br />

Reason, which worshipped<br />

the ‘goddess<br />

of reason’, and the<br />

Cult of the Supreme<br />

Being, created by Maximilien<br />

Robespierre with the intent of<br />

making it the new state religion. This<br />

sought to replicate the benefits of previous<br />

religious practice (the encouragement of<br />

moral behaviour by suggesting that the<br />

soul is immortal) without the drawbacks<br />

of excessive Church power. Unfortunately<br />

for Robespierre, the new cults attracted<br />

barely any interest, aside from a little in<br />

urban areas. Rather than replacing Catholicism,<br />

all that the dechristianisation<br />

movement had achieved was forcing religious<br />

practice to become private.<br />

Whilst many worshipped privately in<br />

their homes, other members of the laity, in<br />

the absence of priests, took matters into<br />

their own hands and performed services<br />

themselves. <strong>The</strong> Convention recognised<br />

the changes that had come about and realised<br />

that they would be forced to accommodate<br />

such private religious practice.<br />

Thus, on 21 February<br />

1795, Church and<br />

State were formally<br />

separated. This involved<br />

the reopening<br />

of Churches and the<br />

release of refractory<br />

priests from prison.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se priests were<br />

now permitted to<br />

practice alongside<br />

constitutional priests<br />

as long as they<br />

vowed to honour the<br />

rules of the Republic.<br />

Despite the relaxed<br />

restrictions, the state<br />

continued to view religion<br />

as a threat to<br />

the new Republic. For<br />

this reason, the public<br />

ban on religious statues<br />

and clothing remained.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was a<br />

blip in this new relationship,<br />

with the<br />

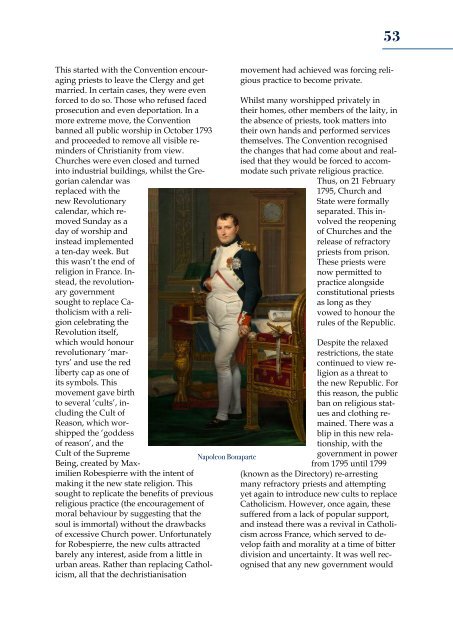

Napoleon Bonaparte<br />

government in power<br />

from 1795 until 1799<br />

(known as the Directory) re-arresting<br />

many refractory priests and attempting<br />

yet again to introduce new cults to replace<br />

Catholicism. However, once again, these<br />

suffered from a lack of popular support,<br />

and instead there was a revival in Catholicism<br />

across France, which served to develop<br />

faith and morality at a time of bitter<br />

division and uncertainty. It was well recognised<br />

that any new government would