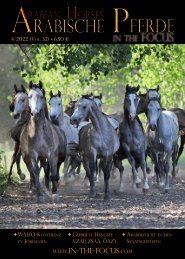

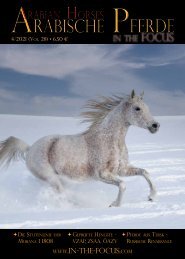

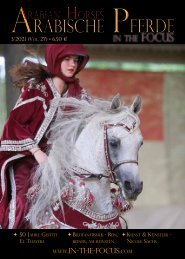

Arabische Pferde IN THE FOCUS Nr. 1/2020 (Vol. 21) - Preview

Die Zeitschrift für Freunde und Züchter arabischer Pferde

Die Zeitschrift für Freunde und Züchter arabischer Pferde

Erfolgreiche ePaper selbst erstellen

Machen Sie aus Ihren PDF Publikationen ein blätterbares Flipbook mit unserer einzigartigen Google optimierten e-Paper Software.

for racing over the centuries. In the 17th and<br />

18th centuries, the races consisted of a race of<br />

only two horses against each other. The winners<br />

of such a two-horse race had to compete<br />

against each other again, etc. The length of<br />

the races was between 3,200 and 6,400 m. Therefore,<br />

the winner had to be able to run long<br />

distances as well as several races per day. This<br />

required endurance horses (stayers), no sprinters.<br />

In addition, the horses were much older<br />

than today, namely 5 to 6 years old, not two<br />

to three years old. In the late 18th and early<br />

19th centuries, racing changed. The races<br />

became shorter (1,600 to 2,800 m), the horses<br />

younger (three years old) - and this trend has<br />

continued to this day. This also shifted the occurrence<br />

of the T / T genotype in favor of the C<br />

/ C genotype, which was present in the population<br />

at that time, but with a low frequency.<br />

Everyone can think about what this means<br />

for Arab race horse breeding, because here,<br />

too, we see a tendency towards short distances<br />

and towards early mature horses, which<br />

actually selects against the typical Arab characteristics.<br />

It could also explain why it is so<br />

tempting to cross (secretly) English sprinter<br />

blood into the Arab breed.<br />

Other factors<br />

In the meantime it turned out that the inheritance<br />

of speed does not seem to be that<br />

easy. The MSTN test (a genetic test) was started<br />

to predict the suitability of racehorses for<br />

different distances, even before they started<br />

training. But the more horses were tested on<br />

MSTN, the less the predictions were true. Petersen<br />

et al. 2014 was able to show that not<br />

only the CC, TC and TT variants play a role in<br />

racing. Rather, it was realized that in addition<br />

to the mutation of the myostatin gene,<br />

a S<strong>IN</strong>E insertion (i.e. the insertion of DNA<br />

sequences into the genome that are only<br />

100-400 base pairs long) can influence the<br />

suitability for certain race distances. Horses<br />

without S<strong>IN</strong>E insertions are generally long<br />

distance horses, those with one copy are<br />

Milers (their preference is therefore approx.<br />

1600 m), and those with two copies show<br />

up as sprinters. At the same time, it turned<br />

out that in Quarter Horse this phenomenon<br />

is also associated with the proportion of different<br />

fiber types in the skeletal muscles. For<br />

a long time, various types of muscle fibers<br />

in horses have been known. A distinction<br />

is made between types I and II, the former<br />

being held responsible for endurance performance<br />

and occurring more frequently in the<br />

Arabian horse, and type II is standing for the<br />

ability to sprint and increasingly occurring<br />

in the English Thoroughbred and Quarter<br />

Horse - and of course there are mixed types<br />

here too. It is also known that other genes<br />

besides MSTN also influence the composition<br />

of the muscle fiber types. And last but not<br />

least, muscles are not everything, you also<br />

need the will to win!<br />

Effective cooling<br />

To achieve a high level of performance, effective<br />

muscle work is required. One characteristic<br />

of the muscles, however, is that they<br />

produce heat as a waste product, which the<br />

body has to get rid of again - that means, the<br />

body also needs an effective cooling system.<br />

This is done by convection. Convection plays<br />

an important role in physical thermoregulation.<br />

For example, if the body is overheated<br />

by muscle activity, increased sweating and<br />

peripheral vasodilation (widening of the<br />

blood vessels) are triggered. Sweat cools very<br />

effectively by removing heat from the body<br />

through evaporation and thus keeping the<br />

body temperature constant. Basically, however,<br />

the fur significantly hinders the evaporation<br />

of sweat, and thus the cooling. Therefore,<br />

horses have a very special protein in their<br />

sweat, the Latherin. Latherin was discovered<br />

in 1982 and named after the English verb 'to<br />

lather'. It is even a predominant part of horse<br />

sweat because it makes up about 80% of<br />

the protein in horse sweat. Latherin acts like<br />

a kind of surfactant and reduces the surface<br />

tension of the sweat water. The result is that<br />

sweat can wet the oily horse fur much more<br />

easily and consequently evaporate and cool<br />

better. Latherin also creates the foamy sweat<br />

that is visible when the horse works hard,<br />

especially where equipment rubs against the<br />

horse's body.<br />

Samantha Brooks took a closer look at this<br />

protein and found that the Arabian horse has<br />

far more copies of the Latherin gene than expected.<br />

She looked at the number of copies of<br />

the Latherin gene in horses of different breeds<br />

and found that the English Thoroughbred<br />

has four copies, the Arabian purebred even<br />

more. It appears that endurance horses from<br />

southern regions have more copies of Latherin<br />

genes than less athletic breeds that have<br />

historically come from a cooler geographic<br />

region, such as miniature horses, which derived<br />

from Shetland ponies and the Percheron.<br />

But this is a first working hypothesis based on<br />

a small number of horses and further investigations<br />

have to follow in order to be able to<br />

make a conclusive statement.<br />

Incidentally, there are only a few mammals<br />

that use sweat for heat regulation. This includes<br />

the equidae, and here mainly the horse,<br />

the camel and the humans!<br />

Gudrun Waiditschka<br />

Weiterführende Literature - Further Reading<br />

McDonald RE, Fleming RI, Beeley JG, Bovell DL, Lu JR, et al. (2009) Latherin: A Surfactant<br />

Protein of Horse Sweat and Saliva. PLoS ONE 4(5): e5726. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005726<br />

Bower, M.A. et al. The genetic origin and history of speed in the Thoroughbred racehorse.<br />

Nat. Commun. 3:643 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1644 (2012).<br />

Ropka-Molik, K. et. al (2019): The Genetics of Racing Performance in Arabian Horses.<br />

Hindawi International Journal of Genomics, <strong>Vol</strong>ume 2019, Article ID 9013239, 8 pages,<br />

https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9013239.<br />

Rooney MF, Hill EW, Kelly VP, Porter RK (2018) The “speed gene” effect of myostatin arises<br />

in Thoroughbred horses due to a promoter proximal S<strong>IN</strong>E insertion. PLoS ONE 13(10):<br />

e0205664. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205664<br />

Meyer, Hanspeter: Funktionelle Genomforschung beim <strong>Vol</strong>lblut (eine Publikation des<br />

Verband Schweizer. <strong>Pferde</strong>zuchtorganisationen)<br />

Brooks, Samantha (2016) Vortrag anläßlich der WAHO-Konferenz.<br />

Breeding<br />

To achieve a high level of<br />

performance, you need<br />

effective muscle work and a<br />

good cooling system.<br />

1/<strong>2020</strong> - www.in-the-focus.com<br />

31