- Page 1 and 2:

Business Finance Theory and Practic

- Page 3 and 4:

We work with leading authors to dev

- Page 5 and 6:

Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh

- Page 7 and 8:

Contents 3 Financial (accounting) s

- Page 9 and 10:

Contents 7.12 Arbitrage pricing mod

- Page 11 and 12:

Contents 12.6 Dividends: the eviden

- Page 13 and 14:

Guided tour of the book Objectives

- Page 15 and 16:

Supporting resources Visit www.pear

- Page 17 and 18:

Preface updated and expanded. Where

- Page 20:

PART 1 The business finance environ

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter 1 • Introduction 1.1 The

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter 1 • Introduction 1.3 The

- Page 27 and 28:

Chapter 1 • Introduction Since it

- Page 29 and 30:

Chapter 1 • Introduction Where di

- Page 31 and 32:

Chapter 1 • Introduction concerne

- Page 33 and 34:

Chapter 1 • Introduction Borrowin

- Page 35 and 36:

Chapter 1 • Introduction time is

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter 1 • Introduction Private

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 41 and 42:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 43 and 44:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 45 and 46:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 59 and 60:

Chapter 2 • A framework for finan

- Page 61 and 62:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 63 and 64:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 65 and 66:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 67 and 68:

Openmirrors.com Chapter 3 • Finan

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 73 and 74:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 75 and 76:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 77 and 78:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 85 and 86:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 87 and 88:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 89 and 90:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 91 and 92:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 93 and 94:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 95 and 96:

Chapter 3 • Financial statements

- Page 98 and 99:

Chapter 4 Investment appraisal meth

- Page 100 and 101:

Net present value (most unlikely in

- Page 102 and 103:

Net present value Investment opport

- Page 104 and 105:

Net present value The process, show

- Page 106 and 107:

Openmirrors.com Internal rate of re

- Page 108 and 109:

Internal rate of return Year Cash f

- Page 110 and 111:

Internal rate of return opportunity

- Page 112 and 113:

Internal rate of return However, no

- Page 114 and 115:

Payback period Continuing to assess

- Page 116 and 117:

Accounting (unadjusted) rate of ret

- Page 118 and 119:

Investment appraisal methods used i

- Page 120 and 121:

Investment appraisal methods used i

- Page 122 and 123:

Investment appraisal methods used i

- Page 124 and 125:

Further reading l Conclusions on PB

- Page 126 and 127:

Problems Calculate: (a) the net pre

- Page 128 and 129:

Problems 4.6 Cool Ltd’s main fina

- Page 130 and 131:

Chapter 5 Practical aspects of inve

- Page 132 and 133:

Cash flows or accounting flows? Inv

- Page 134 and 135:

Do cash flows really occur at year

- Page 136 and 137:

Taxation Forecasting cash flows Inv

- Page 138 and 139:

Taxation Having considered the basi

- Page 140 and 141:

An example of an investment apprais

- Page 142 and 143:

An example of an investment apprais

- Page 144 and 145:

An example of an investment apprais

- Page 146 and 147:

Capital rationing Example 5.6 A bus

- Page 148 and 149:

Capital rationing There is no mathe

- Page 150 and 151:

Replacement decisions Helpful but l

- Page 152 and 153:

Routines for use with investment pr

- Page 154 and 155:

Investment appraisal and strategic

- Page 156 and 157:

Value-based management Select strat

- Page 158 and 159:

Value-based management Corporation

- Page 160 and 161:

l l Value-based management Use capi

- Page 162 and 163:

Real options 5.13 Real options ‘

- Page 164 and 165:

Summary Capital rationing l l l l M

- Page 166 and 167:

Problems PROBLEMS Sample answers to

- Page 168 and 169:

Problems by 31 December 20X7. The c

- Page 170 and 171:

Problems Based on an estimated cons

- Page 172 and 173:

Chapter 6 Risk in investment apprai

- Page 174 and 175:

Sensitivity analysis Example 6.1 Gr

- Page 176 and 177:

Sensitivity analysis (6) Cost of ca

- Page 178 and 179:

Use of probabilities Clearly, these

- Page 180 and 181:

Use of probabilities Solution This

- Page 182 and 183:

Expected value Possible outcome NPV

- Page 184 and 185:

Systematic and specific risk If, ho

- Page 186 and 187:

Utility theory Figure 6.2 Utility o

- Page 188 and 189: Attitudes to risk and expected valu

- Page 190 and 191: Attitudes to risk and expected valu

- Page 192 and 193: Attitudes to risk and expected valu

- Page 194 and 195: Summary Summary Risk l Risk is of v

- Page 196 and 197: Problems REVIEW QUESTIONS Suggested

- Page 198 and 199: Problems Project Initial outlay NPV

- Page 200 and 201: Problems Estimates of the various f

- Page 202 and 203: Problems ‘ There are sets of mult

- Page 204 and 205: The relevance of security prices Th

- Page 206 and 207: Security investment and risk Exampl

- Page 208 and 209: Portfolio theory portfolio. Further

- Page 210 and 211: Portfolio theory Table 7.1 Risk and

- Page 212 and 213: Portfolio theory Figure 7.4 The ris

- Page 214 and 215: Portfolio theory Figure 7.6 The eff

- Page 216 and 217: Portfolio theory tangential to r f

- Page 218 and 219: Capital asset pricing model Beta: a

- Page 220 and 221: CAPM: an example of beta estimation

- Page 222 and 223: CAPM - what went wrong? CAPM has be

- Page 224 and 225: Arbitrage pricing model point is se

- Page 226 and 227: l Portfolio theory - where are we n

- Page 228 and 229: Review questions l l Managers diver

- Page 230 and 231: Appendix: Derivation of CAPM APPEND

- Page 232: Appendix: Derivation of CAPM or E(r

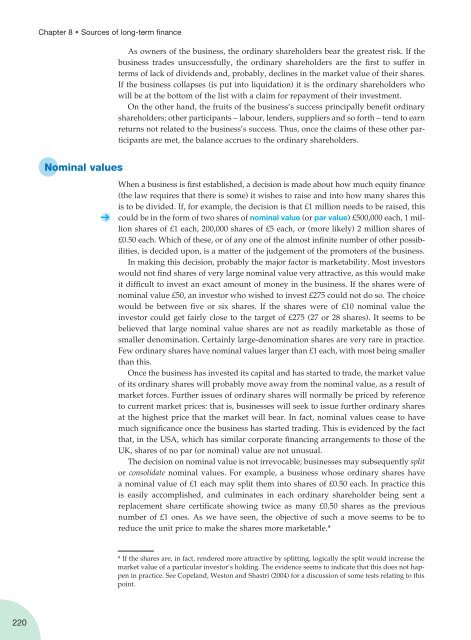

- Page 236 and 237: Chapter 8 Sources of long-term fina

- Page 240 and 241: Ordinary (equity) capital Young and

- Page 242 and 243: Methods of raising additional equit

- Page 244 and 245: Methods of raising additional equit

- Page 246 and 247: Methods of raising additional equit

- Page 248 and 249: Methods of raising additional equit

- Page 250 and 251: Methods of raising additional equit

- Page 252 and 253: Preference shares perspective, than

- Page 254 and 255: Loan notes and debentures are issue

- Page 256 and 257: Loan notes and debentures Methods o

- Page 258 and 259: Loan notes and debentures The relat

- Page 260 and 261: Asset-backed finance (securitisatio

- Page 262 and 263: Leasing from the large first-year a

- Page 264 and 265: Conclusions on long-term finance Br

- Page 266 and 267: Summary l l Rights issue = issue to

- Page 268 and 269: Review questions l This too is quit

- Page 270 and 271: Problems ‘ There are sets of mult

- Page 272 and 273: The London Stock Exchange The exist

- Page 274 and 275: The London Stock Exchange When memb

- Page 276 and 277: Capital market efficiency current s

- Page 278 and 279: Tests of capital market efficiency

- Page 280 and 281: Tests of capital market efficiency

- Page 282 and 283: Tests of capital market efficiency

- Page 284 and 285: Tests of capital market efficiency

- Page 286 and 287: Conclusions and implications would

- Page 288 and 289:

Conclusions and implications winner

- Page 290 and 291:

Further reading l The current price

- Page 292 and 293:

Problems ‘ There are sets of mult

- Page 294 and 295:

Cost of individual capital elements

- Page 296 and 297:

Cost of individual capital elements

- Page 298 and 299:

Cost of individual capital elements

- Page 300 and 301:

Cost of individual capital elements

- Page 302 and 303:

Weighted average cost of capital ta

- Page 304 and 305:

Weighted average cost of capital Th

- Page 306 and 307:

Practicality of using WACC as the d

- Page 308 and 309:

Openmirrors.com Summary figure is s

- Page 310 and 311:

Problems REVIEW QUESTIONS Suggested

- Page 312 and 313:

Problems 10.6 Vocalise plc has rece

- Page 314 and 315:

Is debt finance as cheap as it seem

- Page 316 and 317:

Business risk and financial risk Ta

- Page 318 and 319:

The traditional view 11.4 The tradi

- Page 320 and 321:

The Modigliani and Miller view of g

- Page 322 and 323:

The Modigliani and Miller view of g

- Page 324 and 325:

The Modigliani and Miller view of g

- Page 326 and 327:

Other practical issues relating to

- Page 328 and 329:

l Evidence on gearing a shareholder

- Page 330 and 331:

Gearing and the cost of capital - c

- Page 332 and 333:

Pecking order theory Figure 11.5 Th

- Page 334 and 335:

Weighted average cost of capital re

- Page 336 and 337:

Summary Summary Capital (financial)

- Page 338 and 339:

Problems REVIEW QUESTIONS Suggested

- Page 340 and 341:

Problems A board meeting has been s

- Page 342 and 343:

Appendix I: Proof of the MM cost of

- Page 344 and 345:

Appendix II: Proof of the MM cost o

- Page 346 and 347:

Modigliani and Miller on dividends

- Page 348 and 349:

The traditional view on dividends W

- Page 350 and 351:

l l l l Other factors raising an eq

- Page 352 and 353:

Other factors is interpreted advers

- Page 354 and 355:

l l l Dividends: the evidence a ten

- Page 356 and 357:

Dividends: the evidence attract ins

- Page 358 and 359:

Conclusions on dividends Agency Age

- Page 360 and 361:

Problems l l l l Debt finance - rel

- Page 362 and 363:

Problems It has been estimated that

- Page 364 and 365:

Appendix: Proof of the MM dividend

- Page 366:

PART 4 Integrated decisions There a

- Page 369 and 370:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 371 and 372:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 373 and 374:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 375 and 376:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 377 and 378:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 379 and 380:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 381 and 382:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 383 and 384:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 385 and 386:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 387 and 388:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 389 and 390:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 391 and 392:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 393 and 394:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 395 and 396:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 397 and 398:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 399 and 400:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 401 and 402:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 403 and 404:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 405 and 406:

Chapter 13 • Management of workin

- Page 407 and 408:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 409 and 410:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 411 and 412:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 413 and 414:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 415 and 416:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 417 and 418:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 419 and 420:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 421 and 422:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 423 and 424:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 425 and 426:

Chapter 14 • Corporate restructur

- Page 427 and 428:

Chapter 15 International aspects of

- Page 429 and 430:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 431 and 432:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 433 and 434:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 435 and 436:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 437 and 438:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 439 and 440:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 441 and 442:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 443 and 444:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 445 and 446:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 447 and 448:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 449 and 450:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 451 and 452:

Chapter 15 • International aspect

- Page 453 and 454:

Chapter 16 Small businesses Objecti

- Page 455 and 456:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses The

- Page 457 and 458:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses 16.

- Page 459 and 460:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses sma

- Page 461 and 462:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses l l

- Page 463 and 464:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses Fig

- Page 465 and 466:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses Sol

- Page 467 and 468:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses 16.

- Page 469 and 470:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses l l

- Page 471 and 472:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses REV

- Page 473 and 474:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses Bal

- Page 475 and 476:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses (b)

- Page 477 and 478:

Chapter 16 • Small businesses ‘

- Page 479 and 480:

Appendix 2 Annuity table Present va

- Page 481 and 482:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 483 and 484:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 485 and 486:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 487 and 488:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 489 and 490:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 491 and 492:

Appendix 3 • Suggested answers to

- Page 493 and 494:

Appendix 4 Suggested answers to sel

- Page 495 and 496:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 497 and 498:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 499 and 500:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 501 and 502:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 503 and 504:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 505 and 506:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 507 and 508:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 509 and 510:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 511 and 512:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 513 and 514:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 515 and 516:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 517 and 518:

Appendix 4 • Suggested answers to

- Page 519 and 520:

Glossary Accounting rate of return

- Page 521 and 522:

Glossary Forward (foreign exchange)

- Page 523 and 524:

Glossary of its effective life. It

- Page 525 and 526:

References Aharony, J. and Swary, I

- Page 527 and 528:

References Dimson, E., Marsh, P. an

- Page 529 and 530:

References markets. Journal of Busi

- Page 531 and 532:

Index Note: Page references in bold

- Page 533 and 534:

Index Draper, P. 399 Drury, C. 121,

- Page 535 and 536:

Index Mehrotra, V. 314 Memoranda of

- Page 537:

Index Stock Exchange Automated Quot