UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

11 E.g., United States v. Wilson, 472 F.2d 901 (9th Cir.1972).<br />

12 As for purported abandonment merely by disclaimer of ownership, see § 11.3(a).<br />

13 United States v. Botelho, 360 F.Supp. 620 (D.Hawaii 1973).<br />

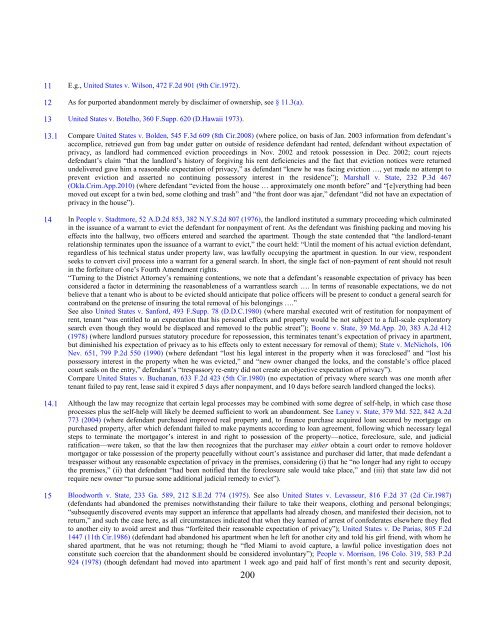

13.1 Compare United States v. Bolden, 545 F.3d 609 (8th Cir.2008) (where police, on basis of Jan. 2003 information from defendant’s<br />

accomplice, retrieved gun from bag under gutter on outside of residence defendant had rented, defendant without expectation of<br />

privacy, as landlord had commenced eviction proceedings in Nov. 2002 and retook possession in Dec. 2002; court rejects<br />

defendant’s claim “that the landlord’s history of forgiving his rent deficiencies and the fact that eviction notices were returned<br />

undelivered gave him a reasonable expectation of privacy,” as defendant “knew he was facing eviction …, yet made no attempt to<br />

prevent eviction and asserted no continuing possessory interest in the residence”); Marshall v. State, 232 P.3d 467<br />

(Okla.Crim.App.2010) (where defendant “evicted from the house … approximately one month before” and “[e]verything had been<br />

moved out except for a twin bed, some clothing and trash” and “the front door was ajar,” defendant “did not have an expectation of<br />

privacy in the house”).<br />

14 In People v. Stadtmore, 52 A.D.2d 853, 382 N.Y.S.2d 807 (1976), the landlord instituted a summary proceeding which culminated<br />

in the issuance of a warrant to evict the defendant for nonpayment of rent. As the defendant was finishing packing and moving his<br />

effects into the hallway, two officers entered and searched the apartment. Though the state contended that “the landlord-tenant<br />

relationship terminates upon the issuance of a warrant to evict,” the court held: “Until the moment of his actual eviction defendant,<br />

regardless of his technical status under property law, was lawfully occupying the apartment in question. In our view, respondent<br />

seeks to convert civil process into a warrant for a general search. In short, the single fact of non-payment of rent should not result<br />

in the forfeiture of one’s Fourth Amendment rights.<br />

“Turning to the District Attorney’s remaining contentions, we note that a defendant’s reasonable expectation of privacy has been<br />

considered a factor in determining the reasonableness of a warrantless search …. In terms of reasonable expectations, we do not<br />

believe that a tenant who is about to be evicted should anticipate that police officers will be present to conduct a general search for<br />

contraband on the pretense of insuring the total removal of his belongings ….”<br />

See also United States v. Sanford, 493 F.Supp. 78 (D.D.C.1980) (where marshal executed writ of restitution for nonpayment of<br />

rent, tenant “was entitled to an expectation that his personal effects and property would be not subject to a full-scale exploratory<br />

search even though they would be displaced and removed to the public street”); Boone v. State, 39 Md.App. 20, 383 A.2d 412<br />

(1978) (where landlord pursues statutory procedure for repossession, this terminates tenant’s expectation of privacy in apartment,<br />

but diminished his expectation of privacy as to his effects only to extent necessary for removal of them); State v. McNichols, 106<br />

Nev. 651, 799 P.2d 550 (1990) (where defendant “lost his legal interest in the property when it was foreclosed” and “lost his<br />

possessory interest in the property when he was evicted,” and “new owner changed the locks, and the constable’s office placed<br />

court seals on the entry,” defendant’s “trespassory re-entry did not create an objective expectation of privacy”).<br />

Compare United States v. Buchanan, 633 F.2d 423 (5th Cir.1980) (no expectation of privacy where search was one month after<br />

tenant failed to pay rent, lease said it expired 5 days after nonpayment, and 10 days before search landlord changed the locks).<br />

14.1 Although the law may recognize that certain legal processes may be combined with some degree of self-help, in which case those<br />

processes plus the self-help will likely be deemed sufficient to work an abandonment. See Laney v. State, 379 Md. 522, 842 A.2d<br />

773 (2004) (where defendant purchased improved real property and, to finance purchase acquired loan secured by mortgage on<br />

purchased property, after which defendant failed to make payments according to loan agreement, following which necessary legal<br />

steps to terminate the mortgagor’s interest in and right to possession of the property—notice, foreclosure, sale, and judicial<br />

ratification—were taken, so that the law then recognizes that the purchaser may either obtain a court order to remove holdover<br />

mortgagor or take possession of the property peacefully without court’s assistance and purchaser did latter, that made defendant a<br />

trespasser without any reasonable expectation of privacy in the premises, considering (i) that he “no longer had any right to occupy<br />

the premises,” (ii) that defendant “had been notified that the foreclosure sale would take place,” and (iii) that state law did not<br />

require new owner “to pursue some additional judicial remedy to evict”).<br />

15 Bloodworth v. State, 233 Ga. 589, 212 S.E.2d 774 (1975). See also United States v. Levasseur, 816 F.2d 37 (2d Cir.1987)<br />

(defendants had abandoned the premises notwithstanding their failure to take their weapons, clothing and personal belongings;<br />

“subsequently discovered events may support an inference that appellants had already chosen, and manifested their decision, not to<br />

return,” and such the case here, as all circumstances indicated that when they learned of arrest of confederates elsewhere they fled<br />

to another city to avoid arrest and thus “forfeited their reasonable expectation of privacy”); United States v. De Parias, 805 F.2d<br />

1447 (11th Cir.1986) (defendant had abandoned his apartment when he left for another city and told his girl friend, with whom he<br />

shared apartment, that he was not returning; though he “fled Miami to avoid capture, a lawful police investigation does not<br />

constitute such coercion that the abandonment should be considered involuntary”); People v. Morrison, 196 Colo. 319, 583 P.2d<br />

924 (1978) (though defendant had moved into apartment 1 week ago and paid half of first month’s rent and security deposit,<br />

200