UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

UNIVERSITY OF THE DISTRICT OF - UDC Law Review

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

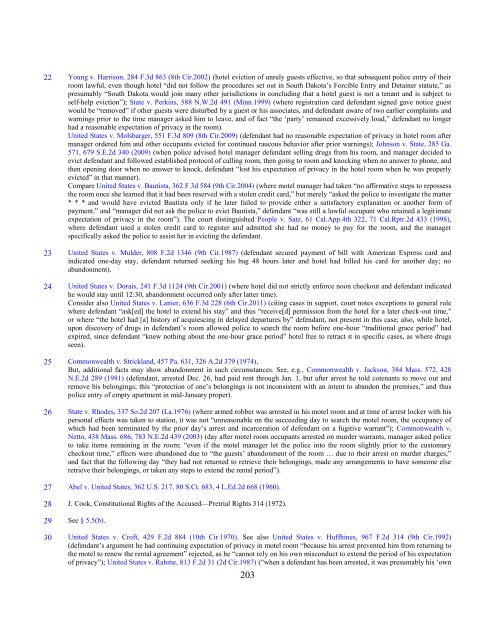

22 Young v. Harrison, 284 F.3d 863 (8th Cir.2002) (hotel eviction of unruly guests effective, so that subsequent police entry of their<br />

room lawful, even though hotel “did not follow the procedures set out in South Dakota’s Forcible Entry and Detainer statute,” as<br />

presumably “South Dakota would join many other jurisdictions in concluding that a hotel guest is not a tenant and is subject to<br />

self-help eviction”); State v. Perkins, 588 N.W.2d 491 (Minn.1999) (where registration card defendant signed gave notice guest<br />

would be “removed” if other guests were disturbed by a guest or his associates, and defendant aware of two earlier complaints and<br />

warnings prior to the time manager asked him to leave, and of fact “the ‘party’ remained excessively loud,” defendant no longer<br />

had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the room).<br />

United States v. Molsbarger, 551 F.3d 809 (8th Cir.2009) (defendant had no reasonable expectation of privacy in hotel room after<br />

manager ordered him and other occupants evicted for continued raucous behavior after prior warnings); Johnson v. State, 285 Ga.<br />

571, 679 S.E.2d 340 (2009) (when police advised hotel manager defendant selling drugs from his room, and manager decided to<br />

evict defendant and followed established protocol of calling room, then going to room and knocking when no answer to phone, and<br />

then opening door when no answer to knock, defendant “lost his expectation of privacy in the hotel room when he was properly<br />

evicted” in that manner).<br />

Compare United States v. Bautista, 362 F.3d 584 (9th Cir.2004) (where motel manager had taken “no affirmative steps to repossess<br />

the room once she learned that it had been reserved with a stolen credit card,” but merely “asked the police to investigate the matter<br />

* * * and would have evicted Bautista only if he later failed to provide either a satisfactory explanation or another form of<br />

payment,” and “manager did not ask the police to evict Bautista,” defendant “was still a lawful occupant who retained a legitimate<br />

expectation of privacy in the room”). The court distinguished People v. Satz, 61 Cal.App.4th 322, 71 Cal.Rptr.2d 433 (1998),<br />

where defendant used a stolen credit card to register and admitted she had no money to pay for the room, and the manager<br />

specifically asked the police to assist her in evicting the defendant.<br />

23 United States v. Mulder, 808 F.2d 1346 (9th Cir.1987) (defendant secured payment of bill with American Express card and<br />

indicated one-day stay, defendant returned seeking his bag 48 hours later and hotel had billed his card for another day; no<br />

abandonment).<br />

24 United States v. Dorais, 241 F.3d 1124 (9th Cir.2001) (where hotel did not strictly enforce noon checkout and defendant indicated<br />

he would stay until 12:30, abandonment occurred only after latter time).<br />

Consider also United States v. Lanier, 636 F.3d 228 (6th Cir.2011) (citing cases in support, court notes exceptions to general rule<br />

where defendant “ask[ed] the hotel to extend his stay” and thus “receive[d] permission from the hotel for a later check-out time,”<br />

or where “the hotel had [a] history of acquiescing in delayed departures by” defendant, not present in this case; also, while hotel,<br />

upon discovery of drugs in defendant’s room allowed police to search the room before one-hour “traditional grace period” had<br />

expired, since defendant “knew nothing about the one-hour grace period” hotel free to retract it in specific cases, as where drugs<br />

seen).<br />

25 Commonwealth v. Strickland, 457 Pa. 631, 326 A.2d 379 (1974).<br />

But, additional facts may show abandonment in such circumstances. See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Jackson, 384 Mass. 572, 428<br />

N.E.2d 289 (1981) (defendant, arrested Dec. 26, had paid rent through Jan. 1, but after arrest he told cotenants to move out and<br />

remove his belongings; this “protection of one’s belongings is not inconsistent with an intent to abandon the premises,” and thus<br />

police entry of empty apartment in mid-January proper).<br />

26 State v. Rhodes, 337 So.2d 207 (La.1976) (where armed robber was arrested in his motel room and at time of arrest locker with his<br />

personal effects was taken to station, it was not “unreasonable on the succeeding day to search the motel room, the occupancy of<br />

which had been terminated by the prior day’s arrest and incarceration of defendant on a fugitive warrant”); Commonwealth v.<br />

Netto, 438 Mass. 686, 783 N.E.2d 439 (2003) (day after motel room occupants arrested on murder warrants, manager asked police<br />

to take items remaining in the room; “even if the motel manager let the police into the room slightly prior to the customary<br />

checkout time,” effects were abandoned due to “the guests’ abandonment of the room … due to their arrest on murder charges,”<br />

and fact that the following day “they had not returned to retrieve their belongings, made any arrangements to have someone else<br />

retrieve their belongings, or taken any steps to extend the rental period”).<br />

27 Abel v. United States, 362 U.S. 217, 80 S.Ct. 683, 4 L.Ed.2d 668 (1960).<br />

28 J. Cook, Constitutional Rights of the Accused—Pretrial Rights 314 (1972).<br />

29 See § 5.5(b).<br />

30 United States v. Croft, 429 F.2d 884 (10th Cir.1970). See also United States v. Huffhines, 967 F.2d 314 (9th Cir.1992)<br />

(defendant’s argument he had continuing expectation of privacy in motel room “because his arrest prevented him from returning to<br />

the motel to renew the rental agreement” rejected, as he “cannot rely on his own misconduct to extend the period of his expectation<br />

of privacy”); United States v. Rahme, 813 F.2d 31 (2d Cir.1987) (“when a defendant has been arrested, it was presumably his ‘own<br />

203