proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Proto-Southwestern Thai 131<br />

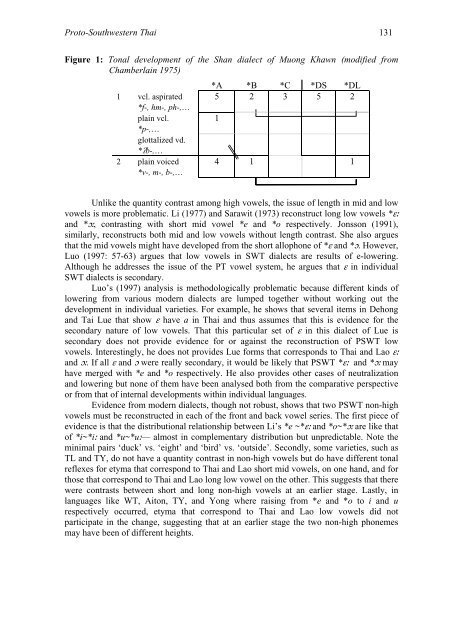

Figure 1: Tonal development of the Shan dialect of Muong Khawn (modified from<br />

Chamberlain 1975)<br />

*A *B *C *DS *DL<br />

1 vcl. aspirated<br />

*f-, hm-, ph-,…<br />

5 2 3 5 2<br />

plain vcl.<br />

*p-,…<br />

glottalized vd.<br />

*ʔb-,…<br />

1<br />

2 plain voiced<br />

*v-, m-, b-,…<br />

4 1 1<br />

Unlike the quantity contrast among high vowels, the issue of length in mid and low<br />

vowels is more problematic. Li (1977) and Sarawit (1973) reconstruct long low vowels *ɛː<br />

and *ɔː, contrasting with short mid vowel *e and *o respectively. Jonsson (1991),<br />

similarly, reconstructs both mid and low vowels without length contrast. She also argues<br />

that the mid vowels might have developed from the short allophone of *ɛ and *ɔ. However,<br />

Luo (1997: 57-63) argues that low vowels in SWT dialects are results of e-lowering.<br />

Although he addresses the issue of the PT vowel system, he argues that ɛ in individual<br />

SWT dialects is secondary.<br />

Luo’s (1997) analysis is methodologically problematic because different kinds of<br />

lowering from various modern dialects are lumped together without working out the<br />

development in individual varieties. For example, he shows that several items in Dehong<br />

and Tai Lue that show ɛ have a in Thai and thus assumes that this is evidence for the<br />

secondary nature of low vowels. That this particular set of ɛ in this dialect of Lue is<br />

secondary does not provide evidence for or against the <strong>reconstruction</strong> of PSWT low<br />

vowels. Interestingly, he does not provides Lue forms that corresponds to Thai and Lao ɛː<br />

and ɔː. If all ɛ and ɔ were really secondary, it would be likely that PSWT *ɛː and *ɔː may<br />

have merged with *e and *o respectively. He also provides other cases of neutralization<br />

and lowering but none of them have been analysed both from the comparative perspective<br />

or from that of internal developments within individual languages.<br />

Evidence from modern dialects, though not robust, shows that two PSWT non-high<br />

vowels must be reconstructed in each of the front and back vowel series. The first piece of<br />

evidence is that the distributional relationship between Li’s *e ~*ɛː and *o~*ɔː are like that<br />

of *i~*iː and *u~*uː— almost in complementary distribution but unpredictable. Note the<br />

minimal pairs ‘duck’ vs. ‘eight’ and ‘bird’ vs. ‘outside’. Secondly, some varieties, such as<br />

TL and TY, do not have a quantity contrast in non-high vowels but do have different tonal<br />

reflexes for etyma that correspond to Thai and Lao short mid vowels, on one hand, and for<br />

those that correspond to Thai and Lao long low vowel on the other. This suggests that there<br />

were contrasts between short and long non-high vowels at an earlier stage. Lastly, in<br />

languages like WT, Aiton, TY, and Yong where raising from *e and *o to i and u<br />

respectively occurred, etyma that correspond to Thai and Lao low vowels did not<br />

participate in the change, suggesting that at an earlier stage the two non-high phonemes<br />

may have been of different heights.