proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

proto-southwestern-tai revised: a new reconstruction - seals 22

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Thai Eventivity & Stativity 91<br />

(door)”, pə̀ət pratuu “open (door), pha� (ba�an)“demolish (house)”, da�p (thian) “blow out<br />

(candle)”, kho�on (to�nma�y) “fell (tree)” (Thepkanjana 2000:267).<br />

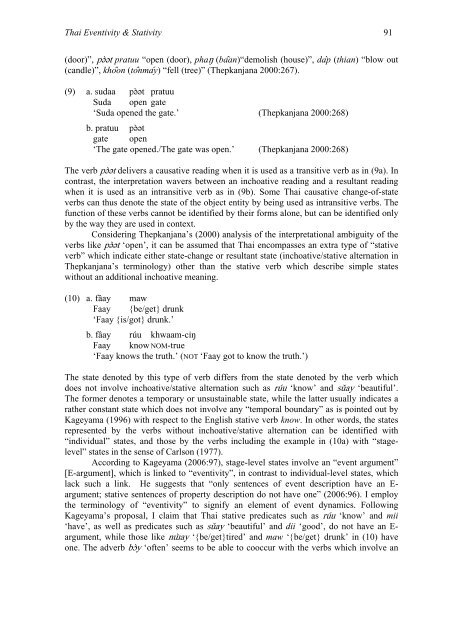

(9) a. sudaa pə̀ət pratuu<br />

Suda open gate<br />

‘Suda opened the gate.’ (Thepkanjana 2000:268)<br />

b. pratuu pə̀ət<br />

gate open<br />

‘The gate opened./The gate was open.’ (Thepkanjana 2000:268)<br />

The verb pə̀ət delivers a causative reading when it is used as a transitive verb as in (9a). In<br />

contrast, the interpretation wavers between an inchoative reading and a resultant reading<br />

when it is used as an intransitive verb as in (9b). Some Thai causative change-of-state<br />

verbs can thus denote the state of the object entity by being used as intransitive verbs. The<br />

function of these verbs cannot be identified by their forms alone, but can be identified only<br />

by the way they are used in context.<br />

Considering Thepkanjana’s (2000) analysis of the interpretational ambiguity of the<br />

verbs like pə̀ət ‘open’, it can be assumed that Thai encompasses an extra type of “stative<br />

verb” which indicate either state-change or resultant state (inchoative/stative alternation in<br />

Thepkanjana’s terminology) other than the stative verb which describe simple states<br />

without an additional inchoative meaning.<br />

(10) a. fâay maw<br />

Faay {be/get} drunk<br />

‘Faay {is/got} drunk.’<br />

b. fâay rúu khwaam-ciŋ<br />

Faay know NOM-true<br />

‘Faay knows the truth.’ (NOT ‘Faay got to know the truth.’)<br />

The state denoted by this type of verb differs from the state denoted by the verb which<br />

does not involve inchoative/stative alternation such as rúu ‘know’ and sǔay ‘beautiful’.<br />

The former denotes a temporary or unsus<strong>tai</strong>nable state, while the latter usually indicates a<br />

rather constant state which does not involve any “temporal boundary” as is pointed out by<br />

Kageyama (1996) with respect to the English stative verb know. In other words, the states<br />

represented by the verbs without inchoative/stative alternation can be identified with<br />

“individual” states, and those by the verbs including the example in (10a) with “stagelevel”<br />

states in the sense of Carlson (1977).<br />

According to Kageyama (2006:97), stage-level states involve an “event argument”<br />

[E-argument], which is linked to “eventivity”, in contrast to individual-level states, which<br />

lack such a link. He suggests that “only sentences of event description have an Eargument;<br />

stative sentences of property description do not have one” (2006:96). I employ<br />

the terminology of “eventivity” to signify an element of event dynamics. Following<br />

Kageyama’s proposal, I claim that Thai stative predicates such as rúu ‘know’ and mii<br />

‘have’, as well as predicates such as sǔay ‘beautiful’ and dii ‘good’, do not have an Eargument,<br />

while those like nɯ̀ ay ‘{be/get}tired’ and maw ‘{be/get} drunk’ in (10) have<br />

one. The adverb bɔ̀y ‘often’ seems to be able to cooccur with the verbs which involve an