Climate Action 2011-2012

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

climate Policy, Governance & Finance<br />

climate negotiations<br />

Advancing the climate regime:<br />

pathways forward from<br />

Copenhagen<br />

While it is possible to imagine technically how progress can<br />

be achieved, the political dynamics are more than tricky.<br />

56 climateactionprogramme.org<br />

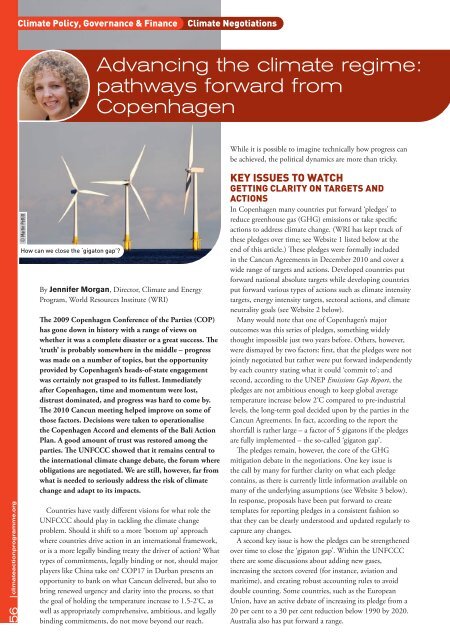

© Martin Pettitt<br />

How can we close the ‘gigaton gap’?<br />

By Jennifer Morgan, Director, <strong>Climate</strong> and Energy<br />

Program, World Resources Institute (WRI)<br />

The 2009 Copenhagen Conference of the Parties (COP)<br />

has gone down in history with a range of views on<br />

whether it was a complete disaster or a great success. The<br />

‘truth’ is probably somewhere in the middle – progress<br />

was made on a number of topics, but the opportunity<br />

provided by Copenhagen’s heads-of-state engagement<br />

was certainly not grasped to its fullest. Immediately<br />

after Copenhagen, time and momentum were lost,<br />

distrust dominated, and progress was hard to come by.<br />

The 2010 Cancun meeting helped improve on some of<br />

those factors. Decisions were taken to operationalise<br />

the Copenhagen Accord and elements of the Bali <strong>Action</strong><br />

Plan. A good amount of trust was restored among the<br />

parties. The UNFCCC showed that it remains central to<br />

the international climate change debate, the forum where<br />

obligations are negotiated. We are still, however, far from<br />

what is needed to seriously address the risk of climate<br />

change and adapt to its impacts.<br />

Countries have vastly different visions for what role the<br />

UNFCCC should play in tackling the climate change<br />

problem. Should it shift to a more ‘bottom up’ approach<br />

where countries drive action in an international framework,<br />

or is a more legally binding treaty the driver of action? What<br />

types of commitments, legally binding or not, should major<br />

players like China take on? COP17 in Durban presents an<br />

opportunity to bank on what Cancun delivered, but also to<br />

bring renewed urgency and clarity into the process, so that<br />

the goal of holding the temperature increase to 1.5-2 º C, as<br />

well as appropriately comprehensive, ambitious, and legally<br />

binding commitments, do not move beyond our reach.<br />

Key issues to watch<br />

GettinG clarity on tarGets and<br />

actions<br />

In Copenhagen many countries put forward ‘pledges’ to<br />

reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or take specific<br />

actions to address climate change. (WRI has kept track of<br />

these pledges over time; see Website 1 listed below at the<br />

end of this article.) These pledges were formally included<br />

in the Cancun Agreements in December 2010 and cover a<br />

wide range of targets and actions. Developed countries put<br />

forward national absolute targets while developing countries<br />

put forward various types of actions such as climate intensity<br />

targets, energy intensity targets, sectoral actions, and climate<br />

neutrality goals (see Website 2 below).<br />

Many would note that one of Copenhagen’s major<br />

outcomes was this series of pledges, something widely<br />

thought impossible just two years before. Others, however,<br />

were dismayed by two factors: first, that the pledges were not<br />

jointly negotiated but rather were put forward independently<br />

by each country stating what it could ‘commit to’; and<br />

second, according to the UNEP Emissions Gap Report, the<br />

pledges are not ambitious enough to keep global average<br />

temperature increase below 2 º C compared to pre-industrial<br />

levels, the long-term goal decided upon by the parties in the<br />

Cancun Agreements. In fact, according to the report the<br />

shortfall is rather large – a factor of 5 gigatons if the pledges<br />

are fully implemented – the so-called ‘gigaton gap’.<br />

The pledges remain, however, the core of the GHG<br />

mitigation debate in the negotiations. One key issue is<br />

the call by many for further clarity on what each pledge<br />

contains, as there is currently little information available on<br />

many of the underlying assumptions (see Website 3 below).<br />

In response, proposals have been put forward to create<br />

templates for reporting pledges in a consistent fashion so<br />

that they can be clearly understood and updated regularly to<br />

capture any changes.<br />

A second key issue is how the pledges can be strengthened<br />

over time to close the ‘gigaton gap’. Within the UNFCCC<br />

there are some discussions about adding new gases,<br />

increasing the sectors covered (for instance, aviation and<br />

maritime), and creating robust accounting rules to avoid<br />

double counting. Some countries, such as the European<br />

Union, have an active debate of increasing its pledge from a<br />

20 per cent to a 30 per cent reduction below 1990 by 2020.<br />

Australia also has put forward a range.