october-2011

october-2011

october-2011

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

once sat on your grandma’s sideboard refl ecting<br />

idealised scenes of pastoral life. Perry brings to<br />

his pottery grim scenes of life on sink estates or<br />

modern icons such as mobile phones, hoodies,<br />

baseball hats and trainers.<br />

It’s a kind of double-take experience: you think you’re<br />

looking at a quaint version of a Japanese Edo jar rendered in<br />

rose pink and gold stencilling, only to realise it’s a scene<br />

depicting Perry dressed as Claire brandishing a doll, chasing<br />

a skinhead. The kind of piece which art historian Jacky Klein<br />

describes as “an uncomfortable clash of form and content”. He<br />

actually named a piece of work I Saw This Vase And Thought It<br />

Beautiful, Then I Looked At It, a comment made by an aunt.<br />

Perry was born in 1960 in Chelmsford, Essex, growing up<br />

unhappily with his mother and stepfather aft er his own father<br />

left the family home following his mother’s aff air. Feeling this<br />

loss keenly, the young Grayson began to create a vivid<br />

imaginary world around his teddy bear character, Alan Measles.<br />

“He became my transition object onto which I projected all my<br />

feelings and he fi gured in all my childhood games. It wasn’t till<br />

I went into therapy that I realised how powerful he was as an<br />

object and that he was a carrier for a lot of my personality,”<br />

he says. These days Alan Measles has his own blog.<br />

Perry fi rst put on a dress around the age of 12 or 13, and found<br />

it helped him process feelings he couldn’t fully make sense of.<br />

“Transvestism wouldn’t exist if children were brought up exactly<br />

the same. It wouldn’t be a reaction against the stereotyping that<br />

goes on. Perhaps it’s a crude way of accessing the emotions of<br />

the opposite gender, but you don’t become a transvestite as an<br />

adult, you decide when you’re a child, very early on.”<br />

It’s not hard to see how his past – splintered relationships,<br />

parental absences, a histrionic mother and a violent,<br />

disapproving stepfather – has fed a preoccupation in his work<br />

with what he has termed “fairytales of dysfunction”.<br />

But at the same time Perry believes the dysfunctional<br />

British family is a fairly normal state for many of us.<br />

In the 1980s he hung out on the periphery of<br />

a cool group of musicians and artists that included<br />

Boy George, Leigh Bowery and Derek Jarman, but<br />

demonstrated his resistance to the whole idea of cool<br />

by embracing a hippy set of friends. This included<br />

a couple of Scottish sisters who enjoyed naturism<br />

and performance art, and dragged young Perry along<br />

“to make up the numbers”.<br />

“They made me see that you had to consciously step outside<br />

of things to make it more interesting. Cool is when creativity<br />

becomes rules and people become like sheep. Irony has gone<br />

so downmarket now.”<br />

College took him to Portsmouth in the early 1980s and later<br />

an artists’ squat in Camden, north London, where he made<br />

fi lms, experimented with drugs (“the opposite of creative”), and<br />

attended free pottery classes that appealed on account of their<br />

unfashionable image. “I realised there was a lot of negativity<br />

around pottery that I could exploit,” he explains. “That it<br />

possessed the kind of values the art world really worries<br />

about: twee, decorative, suburban, sentimental. It considers<br />

them insults, so I’m drawn to them for that reason.”<br />

62 metropolitan<br />

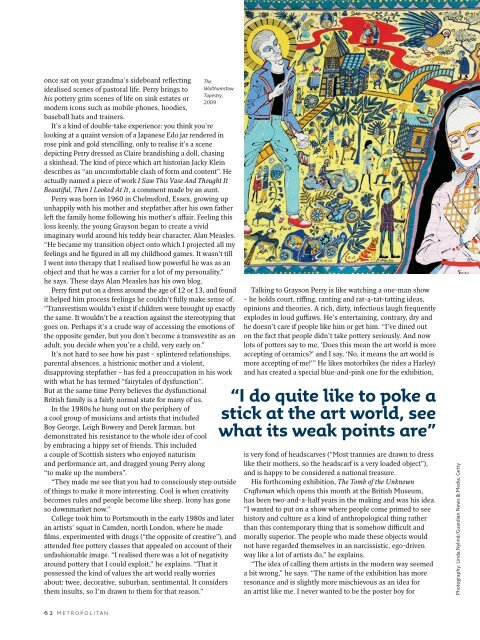

The<br />

Walthamstow<br />

Tapestry,<br />

2009<br />

Talking to Grayson Perry is like watching a one-man show<br />

– he holds court, riffi ng, ranting and rat-a-tat-tatting ideas,<br />

opinions and theories. A rich, dirty, infectious laugh frequently<br />

explodes in loud guff aws. He’s entertaining, contrary, dry and<br />

he doesn’t care if people like him or get him. “I’ve dined out<br />

on the fact that people didn’t take pottery seriously. And now<br />

lots of potters say to me, ‘Does this mean the art world is more<br />

accepting of ceramics?’ and I say, ‘No, it means the art world is<br />

more accepting of me!’” He likes motorbikes (he rides a Harley)<br />

and has created a special blue-and-pink one for the exhibition,<br />

“I do quite like to poke a<br />

stick at the art world, see<br />

what its weak points are”<br />

is very fond of headscarves (“Most trannies are drawn to dress<br />

like their mothers, so the headscarf is a very loaded object”),<br />

and is happy to be considered a national treasure.<br />

His forthcoming exhibition, The Tomb of the Unknown<br />

Craft sman which opens this month at the British Museum,<br />

has been two-and-a-half years in the making and was his idea.<br />

“I wanted to put on a show where people come primed to see<br />

history and culture as a kind of anthropological thing rather<br />

than this contemporary thing that is somehow diffi cult and<br />

morally superior. The people who made these objects would<br />

not have regarded themselves in an narcissistic, ego-driven<br />

way like a lot of artists do,” he explains.<br />

“The idea of calling them artists in the modern way seemed<br />

a bit wrong,” he says. “The name of the exhibition has more<br />

resonance and is slightly more mischievous as an idea for<br />

an artist like me. I never wanted to be the poster boy for<br />

Photography: Linda Nylind/Guardian News & Media; Getty