RESPONSE - Insead

RESPONSE - Insead

RESPONSE - Insead

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Findings: External factors and cognitive alignment (Objective 2) The impact of industry on cognitive gaps<br />

in dealing with uncertainty (Spender, 1989). Where there is such a prevailing way of doing things,<br />

managers may be less disposed to obtain specific feedback from stakeholders. Consequently, where<br />

institutional norms are largely responsible for driving CSR compliance, firms may be moved to copy<br />

competitors’ actions rather than make sense of their own stakeholders’ demands. This leads to the<br />

following hypothesis:<br />

The greater the importance of institutional factors in motivating CSR, the wider the<br />

cognitive gaps (i.e. there will be lower levels of cognitive alignment observed).<br />

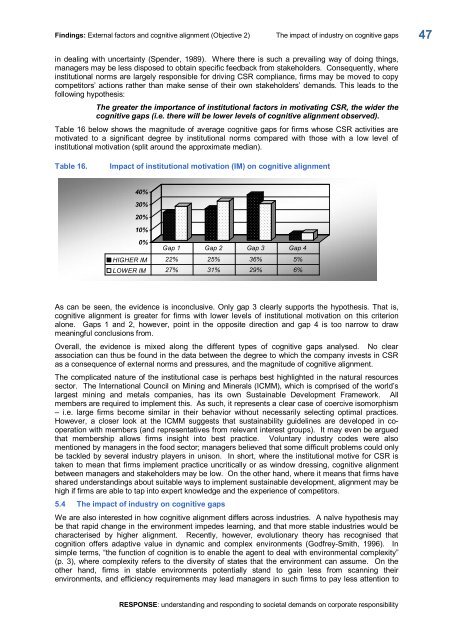

Table 16 below shows the magnitude of average cognitive gaps for firms whose CSR activities are<br />

motivated to a significant degree by institutional norms compared with those with a low level of<br />

institutional motivation (split around the approximate median).<br />

Table 16. Impact of institutional motivation (IM) on cognitive alignment<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Gap 1 Gap 2 Gap 3 Gap 4<br />

HIGHER IM 22% 25% 36% 5%<br />

LOWER IM 27% 31% 29% 6%<br />

As can be seen, the evidence is inconclusive. Only gap 3 clearly supports the hypothesis. That is,<br />

cognitive alignment is greater for firms with lower levels of institutional motivation on this criterion<br />

alone. Gaps 1 and 2, however, point in the opposite direction and gap 4 is too narrow to draw<br />

meaningful conclusions from.<br />

Overall, the evidence is mixed along the different types of cognitive gaps analysed. No clear<br />

association can thus be found in the data between the degree to which the company invests in CSR<br />

as a consequence of external norms and pressures, and the magnitude of cognitive alignment.<br />

The complicated nature of the institutional case is perhaps best highlighted in the natural resources<br />

sector. The International Council on Mining and Minerals (ICMM), which is comprised of the world’s<br />

largest mining and metals companies, has its own Sustainable Development Framework. All<br />

members are required to implement this. As such, it represents a clear case of coercive isomorphism<br />

– i.e. large firms become similar in their behavior without necessarily selecting optimal practices.<br />

However, a closer look at the ICMM suggests that sustainability guidelines are developed in co<br />

operation with members (and representatives from relevant interest groups). It may even be argued<br />

that membership allows firms insight into best practice. Voluntary industry codes were also<br />

mentioned by managers in the food sector; managers believed that some difficult problems could only<br />

be tackled by several industry players in unison. In short, where the institutional motive for CSR is<br />

taken to mean that firms implement practice uncritically or as window dressing, cognitive alignment<br />

between managers and stakeholders may be low. On the other hand, where it means that firms have<br />

shared understandings about suitable ways to implement sustainable development, alignment may be<br />

high if firms are able to tap into expert knowledge and the experience of competitors.<br />

5.4 The impact of industry on cognitive gaps<br />

We are also interested in how cognitive alignment differs across industries. A naïve hypothesis may<br />

be that rapid change in the environment impedes learning, and that more stable industries would be<br />

characterised by higher alignment. Recently, however, evolutionary theory has recognised that<br />

cognition offers adaptive value in dynamic and complex environments (GodfreySmith, 1996). In<br />

simple terms, “the function of cognition is to enable the agent to deal with environmental complexity”<br />

(p. 3), where complexity refers to the diversity of states that the environment can assume. On the<br />

other hand, firms in stable environments potentially stand to gain less from scanning their<br />

environments, and efficiency requirements may lead managers in such firms to pay less attention to<br />

<strong>RESPONSE</strong>: understanding and responding to societal demands on corporate responsibility<br />

47