Untitled - the ultimate blog

Untitled - the ultimate blog

Untitled - the ultimate blog

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Valuing stockmarkets<br />

When <strong>the</strong> signals flash red<br />

Aug 13th 2009<br />

From The Economist print edition<br />

Wall Street Revalued: Imperfect Markets and Inept Central Bankers. By Andrew Smi<strong>the</strong>rs. John<br />

Wiley; 256 pages; $27.95 and £16.99. Buy from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk<br />

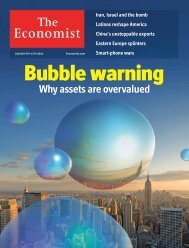

IN EARLY 2000, just as <strong>the</strong> dotcom bubble was at its height, two books appeared that argued <strong>the</strong><br />

stockmarket was overvalued. One, “Irrational Exuberance”, turned its author, Robert Shiller of Yale<br />

University, into something of a guru. The second, “Valuing Wall Street” received less attention but its<br />

insights were no less perceptive. One of its two authors, Andrew Smi<strong>the</strong>rs, a British economist, has now<br />

returned to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of stockmarket valuation. This time he expands his remit to argue that it is not only<br />

possible to ascertain a fair value for stockmarkets but that central banks should try to do so and adjust<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir policies accordingly.<br />

That would once have been a very controversial assertion. It requires central bankers to second guess <strong>the</strong><br />

markets, to assume that <strong>the</strong>y know more about share price values than investors do. Markets were<br />

believed to be efficient, that is to reflect all publicly available information.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> bursting of <strong>the</strong> dotcom bubble followed by <strong>the</strong> credit crunch have dented <strong>the</strong> notion of perfect<br />

markets governed by rational investors. Mr Smi<strong>the</strong>rs prefers <strong>the</strong> idea that markets are “imperfectly<br />

efficient”, in o<strong>the</strong>r words, that <strong>the</strong>y fluctuate around <strong>the</strong>ir fair value.<br />

Having argued this, Mr Smi<strong>the</strong>rs has to demonstrate two things. The first is a reliable method for<br />

valuation, of which he says <strong>the</strong>re are two. One is <strong>the</strong> replacement cost of a company’s assets, <strong>the</strong> socalled<br />

“q” ratio. The o<strong>the</strong>r (which was also an important point in Mr Shiller’s book) is <strong>the</strong> cyclically<br />

adjusted price-earnings ratio, which compares shares with <strong>the</strong> profits earned over <strong>the</strong> previous ten years.<br />

When bull markets have reached <strong>the</strong>ir heights (as in 1929 and 2000), <strong>the</strong>se ratios have clearly indicated<br />

overvaluation. Mr Smi<strong>the</strong>rs makes his case convincingly, dismissing alternative indicators of valuation,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> dividend yield, along <strong>the</strong> way.<br />

But that still leaves Mr Smi<strong>the</strong>rs to deal with a tricky second point: if <strong>the</strong>re is a reliable way of knowing<br />

when markets are overvalued, why haven’t investors used it to make <strong>the</strong>ir fortunes? Moreover, investors<br />

armed with such information would presumably sell <strong>the</strong>ir shares before <strong>the</strong>y reached <strong>the</strong>ir peaks, <strong>the</strong>reby<br />

preventing <strong>the</strong> extremes from being reached in <strong>the</strong> first place.<br />

The answer to this conundrum, which is at <strong>the</strong> heart of efficient market <strong>the</strong>ory, is that valuation is not a<br />

useful guide to stockmarket direction over <strong>the</strong> short term. On Wall Street <strong>the</strong>re were five valuation peaks<br />

in <strong>the</strong> 20th century, or one every 20 years or so. Most investors simply do not have that kind of time<br />

horizon. Get market timing wrong and <strong>the</strong>y may lose a fortune (or, if <strong>the</strong>y are a professional fund<br />

manager, <strong>the</strong>ir clients will). The market can be irrational for longer than you can remain solvent, as <strong>the</strong><br />

saying goes.<br />

A job for <strong>the</strong> banks<br />

Even so, Mr Smi<strong>the</strong>rs argues that central banks should use <strong>the</strong> valuation data to decide whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

stockmarkets are over- extended. And <strong>the</strong>y should look at house prices and <strong>the</strong> price of liquidity (defined<br />

as <strong>the</strong> interest spread on corporate bonds that is not attributable to <strong>the</strong> risk of default) as well. None of<br />

this is easy. But central banks already try to estimate <strong>the</strong> “output gap”, <strong>the</strong> extent to which economic<br />

growth is above or below trend, when setting interest rates—and that’s fiendishly difficult.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past central bankers have claimed that, ra<strong>the</strong>r than try to pop bubbles, <strong>the</strong>y should clean up <strong>the</strong><br />

mess after <strong>the</strong>y have burst. But <strong>the</strong> cost of <strong>the</strong> recent financial crisis makes that policy hard to justify. If<br />

all <strong>the</strong> signals (including house prices and liquidity) are flashing red, <strong>the</strong>n central banks should act. Their<br />

best tool might not be increases in interest rates but changes in <strong>the</strong> capital ratios of banks. By requiring<br />

-130-

![[ccebbook.cn]The Economist August 1st 2009 - the ultimate blog](https://img.yumpu.com/28183607/1/190x252/ccebbookcnthe-economist-august-1st-2009-the-ultimate-blog.jpg?quality=85)

![[ccebook.cn]The World in 2010](https://img.yumpu.com/12057568/1/190x249/ccebookcnthe-world-in-2010.jpg?quality=85)

![[ccemagz.com]The Economist October 24th 2009 - the ultimate blog](https://img.yumpu.com/5191885/1/190x252/ccemagzcomthe-economist-october-24th-2009-the-ultimate-blog.jpg?quality=85)