Untitled - the ultimate blog

Untitled - the ultimate blog

Untitled - the ultimate blog

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A history of classical music finally reaches paperback<br />

A feast for musicians, students and casual concert-goers<br />

Aug 13th 2009<br />

From The Economist print edition<br />

Oxford History of Western Music (five volumes). By Richard<br />

Taruskin. Oxford University Press; 3,856 pages; $185 and £90. Buy<br />

from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk<br />

AKG<br />

“THE feeble beginnings of whatever afterwards becomes great or<br />

eminent are interesting to mankind.” So wrote Charles Burney in<br />

1776, opening his history of music with a subtle apologia for <strong>the</strong><br />

historian’s method. Before Burney, treatises on music had been<br />

<strong>the</strong>oretical, intended for practical use or to elaborate <strong>the</strong> eternal laws<br />

of musical science. The new historical approach brought with it <strong>the</strong><br />

advantage of a more nuanced conception of <strong>the</strong> art, better suited to<br />

a wider public. But as in o<strong>the</strong>r areas of 18th-century learning, history<br />

introduced an element of doubt: had <strong>the</strong>re really been progress from<br />

ancient to modern times? Might today’s music not be worse than it<br />

used to be?<br />

That <strong>the</strong> ancients eventually won <strong>the</strong> argument may be gleaned from<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that we live in an artistic age almost completely dominated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> dead. The modern historian’s task is all <strong>the</strong> more delicate. It<br />

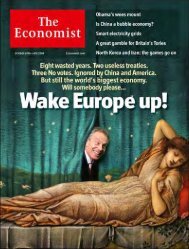

is also lengthier, as is clear from a comparison of Burney’s history Different, but not better or worse<br />

with its contemporary equivalent, Richard Taruskin’s five-volume<br />

work. Since its initial publication at <strong>the</strong> end of 2004, Mr Taruskin’s five-volume survey of 1,200 years of<br />

musical tradition has come in for many criticisms—selectivity, subjectivity, riding roughshod over<br />

contemporary intellectual orthodoxy—but prolixity and over-comprehensiveness have not been among<br />

<strong>the</strong>m.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> original publication of Mr Taruskin’s history sent shock waves through <strong>the</strong> academic musical world,<br />

<strong>the</strong> present reissue of <strong>the</strong> set in paperback is, if anything, a more momentous event. For <strong>the</strong> work,<br />

marvellously awash with judicious reflection on <strong>the</strong> latest scholarship though it is, is not really aimed at<br />

professional scholars. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, its greatest value comes in bringing <strong>the</strong> fruits of advanced scholarship to a<br />

general readership through a compelling, easy-to-read narrative.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> original price of <strong>the</strong> set ($750 or £350), toge<strong>the</strong>r with an internal arrangement that made <strong>the</strong><br />

acquisition of individual volumes impractical, put Mr Taruskin’s efforts beyond <strong>the</strong> reach of those who<br />

might benefit from it <strong>the</strong> most. The new edition is not only much cheaper but its individual volumes are<br />

packaged in a way that allows <strong>the</strong>m to be bought separately.<br />

The book excels for three main reasons. First, as <strong>the</strong> author is keen to point out, this is genuine history.<br />

We are presented not with a miraculous chain of great composers producing timeless masterpieces from<br />

nowhere. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, musical works and stylistic movements are presented in context so that, for example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> origins of <strong>the</strong> dynamic, dramatic style of Mozart and Haydn are shown to lie in Italian opera buffa<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than in <strong>the</strong> architecturally static idiom of Bach and Handel.<br />

Second, and despite <strong>the</strong> sense of flying through <strong>the</strong> terrain at breakneck speed, <strong>the</strong> level of detail remains<br />

high, with extended commentaries on individual works that show how <strong>the</strong>y were originally conceived and<br />

understood. Third, and despite protestations to <strong>the</strong> contrary in his preface, Mr Taruskin’s subjective<br />

preferences make <strong>the</strong>mselves felt throughout <strong>the</strong> weighty five volumes.<br />

That may sound like damning criticism. In fact, <strong>the</strong> author’s numerous bee-infested bonnets are a delight,<br />

as is <strong>the</strong> way his enthusiasms inform, for example, an extended discussion of Debussy or <strong>the</strong> radically<br />

Russophile conception of early 20th-century works. After all, however objective we may aim to be in<br />

historical discussion of <strong>the</strong> arts, <strong>the</strong> truth is that we are interested in art because we like it.<br />

-134-

![[ccebbook.cn]The Economist August 1st 2009 - the ultimate blog](https://img.yumpu.com/28183607/1/190x252/ccebbookcnthe-economist-august-1st-2009-the-ultimate-blog.jpg?quality=85)

![[ccebook.cn]The World in 2010](https://img.yumpu.com/12057568/1/190x249/ccebookcnthe-world-in-2010.jpg?quality=85)

![[ccemagz.com]The Economist October 24th 2009 - the ultimate blog](https://img.yumpu.com/5191885/1/190x252/ccemagzcomthe-economist-october-24th-2009-the-ultimate-blog.jpg?quality=85)