AMEE Berlin 2002 Programme

AMEE Berlin 2002 Programme

AMEE Berlin 2002 Programme

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

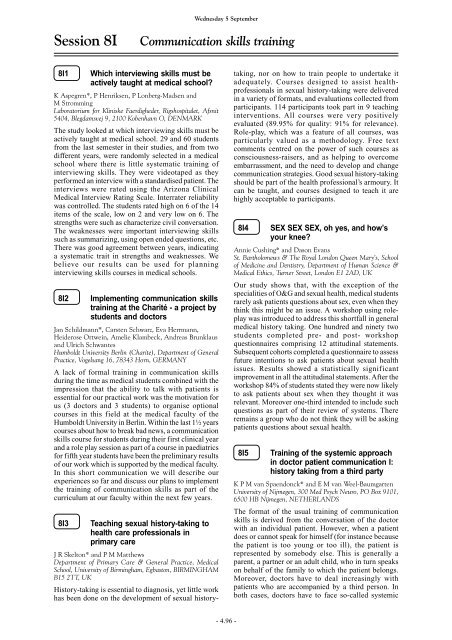

Session 8I Communication skills training<br />

8I1 Which interviewing skills must be<br />

actively taught at medical school?<br />

K Aspegren*, P Henriksen, P Lonberg-Madsen and<br />

M Stromming<br />

Laboratorium for Kliniske Faerdigheder, Rigshospitalet, Afsnit<br />

5404, Blegdamsvej 9, 2100 Kobenhavn O, DENMARK<br />

The study looked at which interviewing skills must be<br />

actively taught at medical school. 29 and 60 students<br />

from the last semester in their studies, and from two<br />

different years, were randomly selected in a medical<br />

school where there is little systematic training of<br />

interviewing skills. They were videotaped as they<br />

performed an interview with a standardised patient. The<br />

interviews were rated using the Arizona Clinical<br />

Medical Interview Rating Scale. Interrater reliability<br />

was controlled. The students rated high on 6 of the 14<br />

items of the scale, low on 2 and very low on 6. The<br />

strengths were such as characterize civil conversation.<br />

The weaknesses were important interviewing skills<br />

such as summarizing, using open ended questions, etc.<br />

There was good agreement between years, indicating<br />

a systematic trait in strengths and weaknesses. We<br />

believe our results can be used for planning<br />

interviewing skills courses in medical schools.<br />

8I2 Implementing communication skills<br />

training at the Charité - a project by<br />

students and doctors<br />

Jan Schildmann*, Carsten Schwarz, Eva Herrmann,<br />

Heiderose Ortwein, Amelie Klambeck, Andreas Brunklaus<br />

and Ulrich Schwantes<br />

Humboldt University <strong>Berlin</strong> (Charite), Department of General<br />

Practice, Vogelsang 16, 78343 Horn, GERMANY<br />

A lack of formal training in communication skills<br />

during the time as medical students combined with the<br />

impression that the ability to talk with patients is<br />

essential for our practical work was the motivation for<br />

us (3 doctors and 3 students) to organise optional<br />

courses in this field at the medical faculty of the<br />

Humboldt University in <strong>Berlin</strong>. Within the last 1½ years<br />

courses about how to break bad news, a communication<br />

skills course for students during their first clinical year<br />

and a role play session as part of a course in paediatrics<br />

for fifth year students have been the preliminary results<br />

of our work which is supported by the medical faculty.<br />

In this short communication we will describe our<br />

experiences so far and discuss our plans to implement<br />

the training of communication skills as part of the<br />

curriculum at our faculty within the next few years.<br />

8I3 Teaching sexual history-taking to<br />

health care professionals in<br />

primary care<br />

J R Skelton* and P M Matthews<br />

Department of Primary Care & General Practice, Medical<br />

School, University of Birmingham, Egbaston, BIRMINGHAM<br />

B15 2TT, UK<br />

History-taking is essential to diagnosis, yet little work<br />

has been done on the development of sexual history-<br />

Wednesday 5 September<br />

- 4.96 -<br />

taking, nor on how to train people to undertake it<br />

adequately. Courses designed to assist healthprofessionals<br />

in sexual history-taking were delivered<br />

in a variety of formats, and evaluations collected from<br />

participants. 114 participants took part in 9 teaching<br />

interventions. All courses were very positively<br />

evaluated (89.95% for quality: 91% for relevance).<br />

Role-play, which was a feature of all courses, was<br />

particularly valued as a methodology. Free text<br />

comments centred on the power of such courses as<br />

consciousness-raisers, and as helping to overcome<br />

embarrassment, and the need to develop and change<br />

communication strategies. Good sexual history-taking<br />

should be part of the health professional’s armoury. It<br />

can be taught, and courses designed to teach it are<br />

highly acceptable to participants.<br />

8I4 SEX SEX SEX, oh yes, and how’s<br />

your knee?<br />

Annie Cushing* and Dason Evans<br />

St. Bartholomews & The Royal London Queen Mary’s, School<br />

of Medicine and Dentistry, Department of Human Science &<br />

Medical Ethics, Turner Street, London E1 2AD, UK<br />

Our study shows that, with the exception of the<br />

specialities of O&G and sexual health, medical students<br />

rarely ask patients questions about sex, even when they<br />

think this might be an issue. A workshop using roleplay<br />

was introduced to address this shortfall in general<br />

medical history taking. One hundred and ninety two<br />

students completed pre- and post- workshop<br />

questionnaires comprising 12 attitudinal statements.<br />

Subsequent cohorts completed a questionnaire to assess<br />

future intentions to ask patients about sexual health<br />

issues. Results showed a statistically significant<br />

improvement in all the attitudinal statements. After the<br />

workshop 84% of students stated they were now likely<br />

to ask patients about sex when they thought it was<br />

relevant. Moreover one-third intended to include such<br />

questions as part of their review of systems. There<br />

remains a group who do not think they will be asking<br />

patients questions about sexual health.<br />

8I5 Training of the systemic approach<br />

in doctor patient communication I:<br />

history taking from a third party<br />

K P M van Spaendonck* and E M van Weel-Baumgarten<br />

University of Nijmegen, 300 Med Psych Neuro, PO Box 9101,<br />

6500 HB Nijmegen, NETHERLANDS<br />

The format of the usual training of communication<br />

skills is derived from the conversation of the doctor<br />

with an individual patient. However, when a patient<br />

does or cannot speak for himself (for instance because<br />

the patient is too young or too ill), the patient is<br />

represented by somebody else. This is generally a<br />

parent, a partner or an adult child, who in turn speaks<br />

on behalf of the family to which the patient belongs.<br />

Moreover, doctors have to deal increasingly with<br />

patients who are accompanied by a third person. In<br />

both cases, doctors have to face so-called systemic