Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

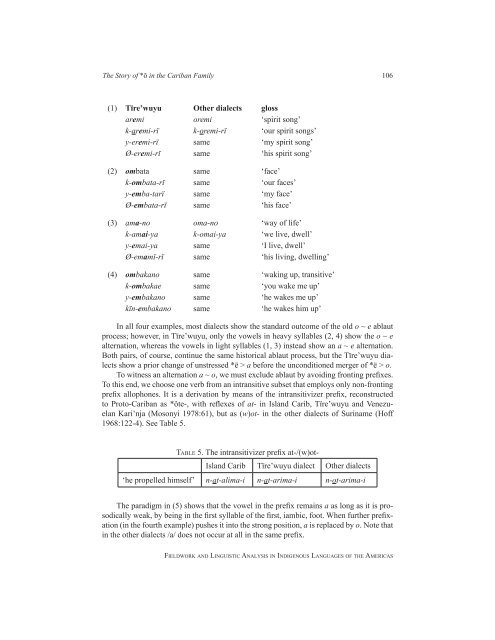

The Story of *ȏ <strong>in</strong> the Cariban Family 106<br />

(1) Tïre’wuyu Other dialects gloss<br />

aremi oremi ‘spirit song’<br />

k-aremi-rï k-oremi-rï ‘our spirit songs’<br />

y-eremi-rï same ‘my spirit song’<br />

Ø-eremi-rï same ‘his spirit song’<br />

(2) ombata same ‘face’<br />

k-ombata-rï same ‘our faces’<br />

y-emba-tarï same ‘my face’<br />

Ø-embata-rï same ‘his face’<br />

(3) ama-no oma-no ‘way of life’<br />

k-amai-ya k-omai-ya ‘we live, dwell’<br />

y-emai-ya same ‘I live, dwell’<br />

Ø-emamï-rï same ‘his liv<strong>in</strong>g, dwell<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

(4) ombakano same ‘wak<strong>in</strong>g up, transitive’<br />

k-ombakae same ‘you wake me up’<br />

y-embakano same ‘he wakes me up’<br />

kïn-embakano same ‘he wakes him up’<br />

In all four examples, most dialects show the st<strong>and</strong>ard outcome of the old o ~ e ablaut<br />

process; however, <strong>in</strong> Tïre’wuyu, only the vowels <strong>in</strong> heavy syllables (2, 4) show the o ~ e<br />

alternation, whereas the vowels <strong>in</strong> light syllables (1, 3) <strong>in</strong>stead show an a ~ e alternation.<br />

Both pairs, of course, cont<strong>in</strong>ue the same historical ablaut process, but the Tïre’wuyu dialects<br />

show a prior change of unstressed *ë > a before the unconditioned merger of *ë > o.<br />

To witness an alternation a ~ o, we must exclude ablaut by avoid<strong>in</strong>g front<strong>in</strong>g prefixes.<br />

To this end, we choose one verb from an <strong>in</strong>transitive subset that employs only non-front<strong>in</strong>g<br />

prefix allophones. It is a derivation by means of the <strong>in</strong>transitivizer prefix, reconstructed<br />

to Proto-Cariban as *ôte-, with reflexes of at- <strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> Carib, Tïre’wuyu <strong>and</strong> Venezuelan<br />

Kari’nja (Mosonyi 1978:61), but as (w)ot- <strong>in</strong> the other dialects of Sur<strong>in</strong>ame (Hoff<br />

1968:122-4). See Table 5.<br />

table 5. The <strong>in</strong>transitivizer prefix at-/(w)ot-<br />

Isl<strong>and</strong> Carib Tïre’wuyu dialect Other dialects<br />

‘he propelled himself’ n-at-alima-i n-at-arima-i n-ot-arima-i<br />

The paradigm <strong>in</strong> (5) shows that the vowel <strong>in</strong> the prefix rema<strong>in</strong>s a as long as it is prosodically<br />

weak, by be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the first syllable of the first, iambic, foot. When further prefixation<br />

(<strong>in</strong> the fourth example) pushes it <strong>in</strong>to the strong position, a is replaced by o. Note that<br />

<strong>in</strong> the other dialects /a/ does not occur at all <strong>in</strong> the same prefix.<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas