Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Outdoors<br />

adventures<br />

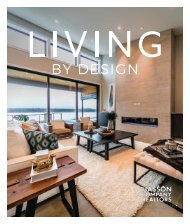

photo courtesy of Alan Watts<br />

photo courtesy of Mike Volk<br />

Suddenly Smith Rock<br />

was a kaleidoscope<br />

of climbers in brightly<br />

colored Lycra tights<br />

and muscle shirts<br />

pushing the limits on<br />

tough sport climbs.<br />

LEFT TO RIGHT Alan Watts sends one<br />

of his projects at Smith Rock. Jean Baptiste<br />

Tribout left and Jean Marc Troussier<br />

with a friend in the Dihedrals, 198.<br />

The Sporting Watts<br />

Necessity was indeed the mother of invention<br />

in the case of piton pioneer Jack Watts’<br />

son, Alan Watts.<br />

Alan Watts’ first climb at Smith Rock was with<br />

a group of friends from Madras High School<br />

when he was 14. Ironically, while Watts and his<br />

father climbed together all over the Cascades<br />

until his early teens, the two never climbed together<br />

at Smith Rock.<br />

"I basically taught myself how to rock climb<br />

and, by my late teens, had started to really focus<br />

on it,” Watts says. “But it wasn't until I was in my<br />

early twenties that I started to get good at it, and<br />

it became my life."<br />

One day in 1982, Watts, then 21, got tired of<br />

climbing all of the established routes and decided<br />

to rappel down big walls to scout their potential.<br />

"I kept seeing all these amazing lines that<br />

looked like they wouldn't go from the ground,<br />

but on rappelling down them, I'd see that they<br />

had plenty of good holds and were indeed<br />

climbable," Watts recalls.<br />

While rappelling down a potential route,<br />

Watts would drill bolts, into which he could<br />

clip protective devices on the ensuing ascent—<br />

a technique later referred to as “rap bolting.” It<br />

was a bold move for the Madras native who had<br />

been a traditional climber since childhood.<br />

In contrast to traditional methods, where<br />

climbers place removeable protection pieces as<br />

well as fixed pitons, Watts tactfully drilled steel<br />

loops, or bolts, at intervals along harder climbs<br />

where traditional gear would not work. In doing<br />

so, Watts opened faces and routes that climbers<br />

previously considered beyond human capability.<br />

With partners such as Chris Grover (now<br />

an executive with climbing gear maker Black<br />

Diamond Equipment in Utah), Watts literally<br />

turned Smith Rock into his own private climbing<br />

area, controversy and all.<br />

A 2010 Rock and Ice magazine feature entitled<br />

"10 Who Influenced” credits the younger<br />

Watts with inventing sport climbing. The story<br />

cited his February 1983 climb of the difficult<br />

5.12-rated Chain Reaction route at Smith Rock<br />

State Park as the first sport climb of record.<br />

Chain Reaction soon lived up to its calling.<br />

This route wasn’t known outside of Oregon until<br />

1986, when it was featured on the cover of<br />

Mountain magazine, the most influential climbing<br />

magazine of the time.<br />

As word about sport climbing spread, controversy<br />

swirled around Watts in the climbing<br />

magazines and among climbers.<br />

To most climbers, sport climbing was akin<br />

to cheating—drilling into rock to affix permanent<br />

bolts in places that would normally be<br />

too dangerous to climb. At the time, American<br />

climbing community icon Royal Robbins<br />

disparaged sport climbing, saying it was as destructive<br />

to the rock as dirt motorcycle riding<br />

was to public lands.<br />

Unfazed, Watts, then 25, headed to the Yosemite<br />

Valley to climb alongside some of rock<br />

climbing's most adamant traditionalists. "I didn't<br />

fear for my life while I was there, but I was scared<br />

that my car might get trashed,” Watts says of the<br />

time spent in Yosemite's Camp Four, where he was<br />

considered a heretic.<br />

While in the Yosemite Valley, he temporarily<br />

suspended his bolt placement sport climbing<br />

technique. "I'd hang on a rope viewing a<br />

route from top to bottom and then come back<br />

later and climb it from the ground up without<br />

any falls,” he says. “The Yosemite climbers<br />

were against my concept at first, but soon<br />

some were giving me credit for climbing the<br />

hard routes they couldn't master by traditional<br />

techniques.”<br />

Prior to going to Yosemite in ’85, Watts had<br />

made the first free ascent (placing protection<br />

as he climbed) of the east side of Monkey<br />

Face, a route that would long hold the distinction<br />

as the hardest route in the country.<br />

Continuing to push the boundaries of<br />

climbing, Watts, by more traditional means,<br />

began to work on a route called “To Bolt or<br />

Not To Be.” Rated an extremely difficult 5.14,<br />

this route superseded all others as the most<br />

difficult rock climb in the U.S. at the time.<br />

In 1986, French climber J.B. Tribout arrived at<br />

Smith to witness climbing’s new playground. In<br />

one push, he flashed up Watt’s project, To Bolt or<br />

Not To Be. Publicity of this climb sparked worldwide<br />

interest in sport climbing and made Smith<br />

Rock famous beyond American borders. Suddenly<br />

Smith Rock was a kaleidoscope of climbers<br />

in brightly colored Lycra tights and muscle<br />

shirts pushing the limits on tough sport climbs.<br />

On a typical day in the ’80s, it wasn’t unusual to<br />

hear a dozen foreign languages echoing between<br />

Smith Rock’s big and bolted walls.<br />

122 <strong>1859</strong> oregon's mAgAzine SEPT OCT <strong>2012</strong>