Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

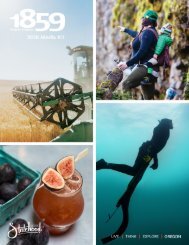

ine Crush<br />

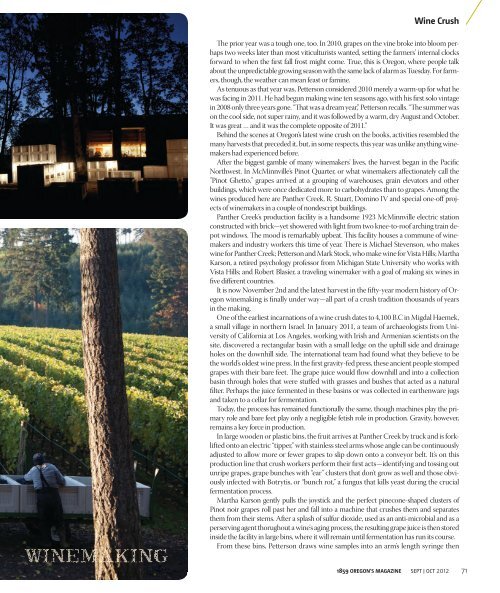

WINEMAKING<br />

The prior year was a tough one, too. In 2010, grapes on the vine broke into bloom perhaps<br />

two weeks later than most viticulturists wanted, setting the farmers’ internal clocks<br />

forward to when the first fall frost might come. True, this is Oregon, where people talk<br />

about the unpredictable growing season with the same lack of alarm as Tuesday. For farmers,<br />

though, the weather can mean feast or famine.<br />

As tenuous as that year was, Petterson considered 2010 merely a warm-up for what he<br />

was facing in 2011. He had begun making wine ten seasons ago, with his first solo vintage<br />

in 2008 only three years gone. “That was a dream year,” Petterson recalls. “The summer was<br />

on the cool side, not super rainy, and it was followed by a warm, dry August and <strong>Oct</strong>ober.<br />

It was great … and it was the complete opposite of 2011.”<br />

Behind the scenes at Oregon’s latest wine crush on the books, activities resembled the<br />

many harvests that preceded it, but, in some respects, this year was unlike anything winemakers<br />

had experienced before.<br />

After the biggest gamble of many winemakers' lives, the harvest began in the Pacific<br />

Northwest. In McMinnville’s Pinot Quarter, or what winemakers affectionately call the<br />

"Pinot Ghetto," grapes arrived at a grouping of warehouses, grain elevators and other<br />

buildings, which were once dedicated more to carbohydrates than to grapes. Among the<br />

wines produced here are Panther Creek, R. Stuart, Domino IV and special one-off projects<br />

of winemakers in a couple of nondescript buildings.<br />

Panther Creek’s production facility is a handsome 1923 McMinnville electric station<br />

constructed with brick—yet showered with light from two knee-to-roof arching train depot<br />

windows. The mood is remarkably upbeat. This facility houses a commune of winemakers<br />

and industry workers this time of year. There is Michael Stevenson, who makes<br />

wine for Panther Creek; Petterson and Mark Stock, who make wine for Vista Hills; Martha<br />

Karson, a retired psychology professor from Michigan State University who works with<br />

Vista Hills; and Robert Blasier, a traveling winemaker with a goal of making six wines in<br />

five different countries.<br />

It is now November 2nd and the latest harvest in the fifty-year modern history of Oregon<br />

winemaking is finally under way—all part of a crush tradition thousands of years<br />

in the making.<br />

One of the earliest incarnations of a wine crush dates to 4,100 B.C in Migdal Haemek,<br />

a small village in northern Israel. In January 2011, a team of archaeologists from University<br />

of California at Los Angeles, working with Irish and Armenian scientists on the<br />

site, discovered a rectangular basin with a small ledge on the uphill side and drainage<br />

holes on the downhill side. The international team had found what they believe to be<br />

the world’s oldest wine press. In the first gravity-fed press, these ancient people stomped<br />

grapes with their bare feet. The grape juice would flow downhill and into a collection<br />

basin through holes that were stuffed with grasses and bushes that acted as a natural<br />

filter. Perhaps the juice fermented in these basins or was collected in earthenware jugs<br />

and taken to a cellar for fermentation.<br />

Today, the process has remained functionally the same, though machines play the primary<br />

role and bare feet play only a negligible fetish role in production. Gravity, however,<br />

remains a key force in production.<br />

In large wooden or plastic bins, the fruit arrives at Panther Creek by truck and is forklifted<br />

onto an electric “tipper,” with stainless steel arms whose angle can be continuously<br />

adjusted to allow more or fewer grapes to slip down onto a conveyor belt. It’s on this<br />

production line that crush workers perform their first acts—identifying and tossing out<br />

unripe grapes, grape bunches with “ear” clusters that don’t grow as well and those obviously<br />

infected with Botrytis, or “bunch rot,” a fungus that kills yeast during the crucial<br />

fermentation process.<br />

Martha Karson gently pulls the joystick and the perfect pinecone-shaped clusters of<br />

Pinot noir grapes roll past her and fall into a machine that crushes them and separates<br />

them from their stems. After a splash of sulfur dioxide, used as an anti-microbial and as a<br />

perserving agent thorughout a wine's aging process, the resulting grape juice is then stored<br />

inside the facility in large bins, where it will remain until fermentation has run its course.<br />

From these bins, Petterson draws wine samples into an arm’s length syringe then<br />

<strong>1859</strong> oregon's mAgAzine SEPT OCT <strong>2012</strong> 1