Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

artist in residence<br />

Local Habit<br />

Returning<br />

to Roots<br />

written by Shirley Hancock<br />

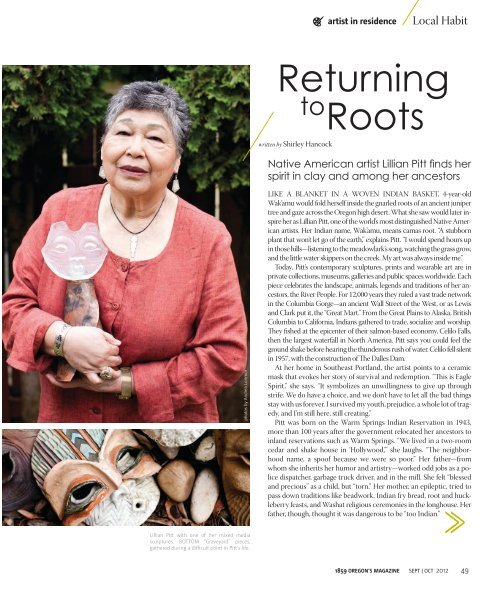

ative American artist illian itt finds her<br />

spirit in clay and among her ancestors<br />

<br />

LIKE A BLANKET IN A WOVEN INDIAN BASKET, 4-year-old<br />

Wak’amu would fold herself inside the gnarled roots of an ancient juniper<br />

tree and gaze across the Oregon high desert. What she saw would later inspire<br />

her as Lillian Pitt, one of the world’s most distinguished Native American<br />

artists. Her Indian name, Wak’amu, means camas root. “A stubborn<br />

plant that won’t let go of the earth,” explains Pitt. “I would spend hours up<br />

in those hills—listening to the meadowlark’s song, watching the grass grow,<br />

and the little water skippers on the creek. My art was always inside me.”<br />

Today, Pitt’s contemporary sculptures, prints and wearable art are in<br />

private collections, museums, galleries and public spaces worldwide. Each<br />

piece celebrates the landscape, animals, legends and traditions of her ancestors,<br />

the River People. For 12,000 years they ruled a vast trade network<br />

in the Columbia Gorge—an ancient Wall Street of the West, or as Lewis<br />

and Clark put it, the “Great Mart.” From the Great Plains to Alaska, British<br />

Columbia to California, Indians gathered to trade, socialize and worship.<br />

They fished at the epicenter of their salmon-based economy, Celilo Falls,<br />

then the largest waterfall in North America. Pitt says you could feel the<br />

ground shake before hearing the thunderous rush of water. Celilo fell silent<br />

in 1957, with the construction of The Dalles Dam.<br />

At her home in Southeast Portland, the artist points to a ceramic<br />

mask that evokes her story of survival and redemption. “This is Eagle<br />

Spirit,” she says. “It symbolizes an unwillingness to give up through<br />

strife. We do have a choice, and we don’t have to let all the bad things<br />

stay with us forever. I survived my youth, prejudice, a whole lot of tragedy,<br />

and I’m still here, still creating.”<br />

Pitt was born on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in 1943,<br />

more than 100 years after the government relocated her ancestors to<br />

inland reservations such as Warm Springs. “We lived in a two-room<br />

cedar and shake house in ‘Hollywood,’” she laughs. “The neighborhood<br />

name, a spoof because we were so poor.” Her father—from<br />

whom she inherits her humor and artistry—worked odd jobs as a police<br />

dispatcher, garbage truck driver, and in the mill. She felt “blessed<br />

and precious” as a child, but “torn.” Her mother, an epileptic, tried to<br />

pass down traditions like beadwork, Indian fry bread, root and huckleberry<br />

feasts, and Washat religious ceremonies in the longhouse. Her<br />

father, though, thought it was dangerous to be “too Indian.”<br />

P <br />

G <br />

P <br />

<strong>1859</strong> oregon's mAgAzine SEPT OCT <strong>2012</strong> 4