2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines - Canadian Diabetes Association

2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines - Canadian Diabetes Association

2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines - Canadian Diabetes Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

have failed to demonstrate an improvement in glycated hemoglobin<br />

(A1C) compared with MDI. However, almost all clinic-based<br />

studies of CSII in school-aged children and<br />

adolescents have shown a significant reduction in A1C with<br />

reduced hypoglycemia 12 to 24 months after initiation of CSII<br />

when compared to pre-CSII levels (15).<br />

Most, but not all, pediatric studies of the extended longacting<br />

insulin analogues detemir and glargine have demonstrated<br />

improved fasting BG levels and fewer episodes of<br />

nocturnal hypoglycemia with a reduction in A1C (16-18).<br />

GLUCOSE MONITORING<br />

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is an essential part<br />

of management of type 1 diabetes (19). Subcutaneous continuous<br />

glucose sensors have demonstrated good accuracy except<br />

when BG levels are in the hypoglycemic range (20-22).<br />

Continuous glucose sensors may be a useful tool for improving<br />

glycemic control in individuals on intensive therapy (23).<br />

NUTRITION<br />

All children with type 1 diabetes should receive counselling<br />

from a registered dietitian experienced in pediatric diabetes.<br />

Children with diabetes should follow a healthy diet, as recommended<br />

for children without diabetes in Eating Well with<br />

Canada’s Food Guide (24).This involves consuming a variety of<br />

foods from the 4 food groups (grain products, vegetables and<br />

fruits, milk and alternatives, meat and alternatives). There is<br />

no evidence that one form of nutrition therapy is superior<br />

to another in attaining age-appropriate glycemic targets.<br />

Appropriate matching of insulin to carbohydrate content may<br />

allow increased flexibility and improved glycemic control<br />

(25,26), but the use of insulin to carbohydrate ratios is not<br />

required.The effect of protein and fat on glucose absorption<br />

must also be considered. Nutrition therapy should be individualized<br />

(based on the child’s nutritional needs, eating habits,<br />

lifestyle, ability and interest) and must ensure normal growth<br />

and development without compromising glycemic control.<br />

This plan should be evaluated regularly and at least annually.<br />

HYPOGLYCEMIA<br />

Hypoglycemia is a major obstacle for children with type 1 diabetes<br />

and can affect their ability to achieve glycemic targets.<br />

Significant risk of hypoglycemia often necessitates less stringent<br />

glycemic goals, particularly for younger children. Severe<br />

hypoglycemia should be treated with pediatric doses of intravenous<br />

(IV) dextrose in the hospital setting, or glucagon in<br />

the home setting. In children, the use of mini-doses of<br />

glucagon has been shown useful in the home management of<br />

mild or impending hypoglycemia associated with inability or<br />

refusal to take oral carbohydrate. A dose of 20 µg per year of<br />

age up to a maximum of 150 µg is effective at treating and<br />

preventing hypoglycemia, with an additional doubled dose<br />

given if the BG has not increased in 20 minutes (27,28).<br />

CHRONIC POOR METABOLIC CONTROL<br />

<strong>Diabetes</strong> control may worsen during adolescence. Factors<br />

responsible for this deterioration include adolescent adjustment<br />

issues, psychosocial distress, intentional insulin<br />

omission and physiologic insulin resistance. A careful multidisciplinary<br />

assessment should be undertaken for every child<br />

with chronic poor metabolic control (e.g. A1C >10.0%) to<br />

identify potential causative factors such as depression and eating<br />

disorders and to identify and address barriers to improved<br />

control (29,30).<br />

DKA<br />

DKA occurs in 15 to 67% of children with new-onset diabetes<br />

and at a frequency of 1 to 10 episodes per 100 patient<br />

years in those with established diabetes (31). As DKA is the<br />

leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children with<br />

diabetes (32), strategies are required to prevent the development<br />

of DKA. In new-onset diabetes, DKA can be prevented<br />

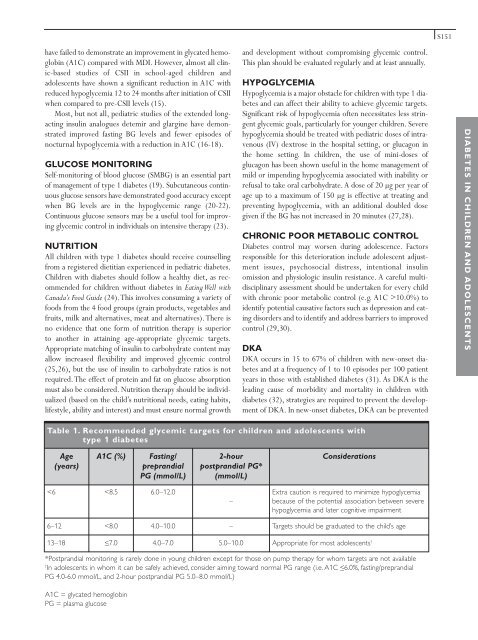

Table 1. Recommended glycemic targets for children and adolescents with<br />

type 1 diabetes<br />

Age<br />

(years)<br />

*Postprandial monitoring is rarely done in young children except for those on pump therapy for whom targets are not available<br />

† In adolescents in whom it can be safely achieved, consider aiming toward normal PG range (i.e. A1C ≤6.0%, fasting/preprandial<br />

PG 4.0-6.0 mmol/L, and 2-hour postprandial PG 5.0–8.0 mmol/L)<br />

A1C = glycated hemoglobin<br />

PG = plasma glucose<br />

A1C (%) Fasting/<br />

preprandial<br />

PG (mmol/L)<br />