- Page 1 and 2:

Dezembro de 2007 Revista de Letras

- Page 3 and 4:

REVISTA DE LETRAS Direcção Carlos

- Page 5 and 6:

LITERATURA Two Perspectives of Euth

- Page 7 and 8:

6 Nota Introdutória Quanto às tem

- Page 10 and 11:

Para além-mar e para além da orto

- Page 12 and 13:

Para além-mar e para além da orto

- Page 14 and 15:

Para além-mar e para além da orto

- Page 16 and 17:

Para além-mar e para além da orto

- Page 18 and 19:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 20 and 21:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 22 and 23:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 24 and 25:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 26 and 27:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 28 and 29:

Point of view in Pérez-Reverte’s

- Page 30 and 31:

Le jugement de valeur - 2 - André

- Page 32 and 33:

Le Jugement de Valeur 31 Vilela, on

- Page 34 and 35:

Le Jugement de Valeur 33 «Bien que

- Page 36:

Le Jugement de Valeur 35 En revanch

- Page 39 and 40:

38 Maria Filomena Gonçalves intens

- Page 41 and 42:

40 Maria Filomena Gonçalves latina

- Page 43 and 44:

42 Maria Filomena Gonçalves public

- Page 45 and 46:

44 Maria Filomena Gonçalves conhec

- Page 47 and 48:

46 Maria Filomena Gonçalves 5. Uma

- Page 49 and 50:

48 Maria Filomena Gonçalves Torres

- Page 51 and 52:

50 Maria Filomena Gonçalves Anexo

- Page 54 and 55:

Património, Língua e Cultura: con

- Page 56 and 57:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 58 and 59:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 60 and 61:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 62 and 63:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 64 and 65:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 66 and 67:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 68 and 69:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 70 and 71:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 72:

Património, Língua e Cultura: Con

- Page 75 and 76:

74 Rui Dias Guimarães 1. Introduç

- Page 77 and 78:

76 Rui Dias Guimarães A norma, de

- Page 79 and 80:

78 Rui Dias Guimarães É, sem dúv

- Page 81 and 82:

80 Rui Dias Guimarães A notável i

- Page 83 and 84:

82 Rui Dias Guimarães Cunha, C. E

- Page 85 and 86:

84 Marlene Vasques Loureiro On peut

- Page 87 and 88:

86 Marlene Vasques Loureiro Portant

- Page 89 and 90:

88 Marlene Vasques Loureiro d’en

- Page 91 and 92:

90 Marlene Vasques Loureiro Si ce m

- Page 93 and 94:

92 Marlene Vasques Loureiro afirman

- Page 95 and 96:

94 Marlene Vasques Loureiro Broncka

- Page 98 and 99:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 100 and 101:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 102 and 103:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 104 and 105:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 106 and 107:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 108:

Signo e significação no primeiro

- Page 111 and 112:

110 László Magocsa both the learn

- Page 113 and 114:

112 László Magocsa needs a very c

- Page 115 and 116:

114 László Magocsa able to really

- Page 117 and 118:

116 Hiroyuki Mito Na história japo

- Page 119 and 120:

118 Hiroyuki Mito “Tonghae”, es

- Page 121 and 122:

120 Hiroyuki Mito A forma Gipou vir

- Page 123 and 124:

122 Hiroyuki Mito NIPHON. A mayor I

- Page 125 and 126:

124 Hiroyuki Mito q´ então tinha

- Page 127 and 128:

126 Hiroyuki Mito Seguem-se as desc

- Page 129 and 130:

128 Hiroyuki Mito praticamente desa

- Page 131 and 132:

130 Irene López Rodríguez As the

- Page 133 and 134:

132 Irene López Rodríguez Girl, i

- Page 135 and 136:

134 Irene López Rodríguez In the

- Page 137 and 138:

136 Irene López Rodríguez As can

- Page 139 and 140:

138 Irene López Rodríguez IV. - A

- Page 141 and 142:

140 Irene López Rodríguez OBJECT

- Page 143 and 144:

142 Irene López Rodríguez of the

- Page 145 and 146:

144 Irene López Rodríguez (28) In

- Page 147 and 148:

146 Irene López Rodríguez contemp

- Page 149 and 150:

148 Irene López Rodríguez follow

- Page 151 and 152: 150 Irene López Rodríguez Echevar

- Page 153 and 154: 152 Irene López Rodríguez Nesi, H

- Page 156 and 157: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 158 and 159: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 160 and 161: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 162 and 163: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 164 and 165: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 166 and 167: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 168 and 169: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 170 and 171: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 172 and 173: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 174: Tombo e Demarcação do concelho de

- Page 177 and 178: 176 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei arca

- Page 179 and 180: 178 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei ácha

- Page 181 and 182: 180 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei singu

- Page 183 and 184: 182 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei nos l

- Page 185 and 186: 184 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei o da

- Page 187 and 188: 186 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei Tabel

- Page 189 and 190: 188 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei Frecu

- Page 191 and 192: 190 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei demon

- Page 193 and 194: 192 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei Diess

- Page 195 and 196: 194 Xosé Manuel Sánchez Rei Macha

- Page 198 and 199: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 200 and 201: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 204 and 205: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 206 and 207: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 208 and 209: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 210 and 211: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 212 and 213: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 214 and 215: Two Perspectives of Euthanasia in E

- Page 216 and 217: Para além do “Sermão de St.º A

- Page 218 and 219: Para além do “Sermão de St.º A

- Page 220 and 221: Para além do “Sermão de St.º A

- Page 222 and 223: Para além do “Sermão de St.º A

- Page 224 and 225: Formulação histórico-crítica de

- Page 226 and 227: Formulação histórico-crítica de

- Page 228 and 229: Formulação histórico-crítica de

- Page 230 and 231: Formulação histórico-crítica de

- Page 232 and 233: Especificidades da criação liter

- Page 234 and 235: Especificidades da criação liter

- Page 236: Especificidades da criação liter

- Page 239 and 240: 238 M.ª da Assunção Anes Morais

- Page 241 and 242: 240 M.ª da Assunção Anes Morais

- Page 243 and 244: 242 M.ª da Assunção Anes Morais

- Page 245 and 246: 244 M.ª da Assunção Anes Morais

- Page 247 and 248: 246 M.ª da Assunção Anes Morais

- Page 249 and 250: 248 Karen C. Sherwood Sotelino orie

- Page 251 and 252: 250 Karen C. Sherwood Sotelino Gome

- Page 253 and 254:

252 Karen C. Sherwood Sotelino Juxt

- Page 255 and 256:

254 Karen C. Sherwood Sotelino ser

- Page 258:

CULTURA

- Page 261 and 262:

260 António Bárbolo Alves Marquez

- Page 263 and 264:

262 António Bárbolo Alves Numa Pa

- Page 265 and 266:

264 António Bárbolo Alves igualme

- Page 267 and 268:

266 António Bárbolo Alves O teatr

- Page 269 and 270:

268 António Bárbolo Alves A tradi

- Page 271 and 272:

270 António Bárbolo Alves Centro

- Page 273 and 274:

272 António Bárbolo Alves mirande

- Page 275 and 276:

274 António Bárbolo Alves Natural

- Page 278 and 279:

Interculturalidade e tradução Ann

- Page 280 and 281:

Interculturalidade e tradução 279

- Page 282 and 283:

Interculturalidade e tradução 281

- Page 284 and 285:

Interculturalidade e tradução 283

- Page 286 and 287:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 288 and 289:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 290 and 291:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 292 and 293:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 294 and 295:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 296 and 297:

A investigação da escrita no Arch

- Page 298 and 299:

Racial Complexities in the Work of

- Page 300 and 301:

Racial complexities in the work of

- Page 302 and 303:

Racial complexities in the work of

- Page 304 and 305:

Racial complexities in the work of

- Page 306 and 307:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 308 and 309:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 310 and 311:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 312 and 313:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 314 and 315:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 316 and 317:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 318:

Da memória ao acesso à Informaç

- Page 321 and 322:

320 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva Por

- Page 323 and 324:

322 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva trat

- Page 325 and 326:

324 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva vamp

- Page 327 and 328:

326 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva even

- Page 329 and 330:

328 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva merc

- Page 331 and 332:

330 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva mesm

- Page 333 and 334:

332 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva frut

- Page 335 and 336:

334 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva demo

- Page 337 and 338:

336 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva «in

- Page 339 and 340:

338 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva nota

- Page 341 and 342:

340 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva faze

- Page 343 and 344:

342 Francisco Ribeiro da Silva dive

- Page 346 and 347:

Comunicação e Cultura Fernando Al

- Page 348 and 349:

Comunicação e Cultura 347 Apresen

- Page 350 and 351:

Comunicação e Cultura 349 que se

- Page 352:

VARIA

- Page 355 and 356:

354 Recensões desentendimento. As

- Page 357 and 358:

356 Recensões alia-se à flexibili

- Page 359 and 360:

358 Recensões José Manuel da Cost

- Page 361 and 362:

360 Recensões epistolar entre as d

- Page 363 and 364:

362 Recensões Esteves, a alavanca

- Page 365 and 366:

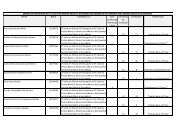

364 Teses de Doutoramento e Dissert

- Page 367 and 368:

366 Teses de Doutoramento e Dissert